Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Tripping the Trail of Ghosts

Psychedelics and the Afterlife Journey in Native American Mound Cultures

Table of Contents

About The Book

• Demonstrates how psychoactive plants were used to evoke the liminal state between life and death in initiatory rites and spirit journeys

• Explores the symbology of the large earthwork mounds erected by the Indigenous people of the Mississippi Valley and how they connect to the Path of Souls

The use of hallucinogenic substances like peyote and desert tobacco has long played a significant role in the spiritual practices and traditions of Native Americans. While the majority of those practices are well documented, the relationship between entheogens and Native Americans of the Southeast has gone largely unexplored.

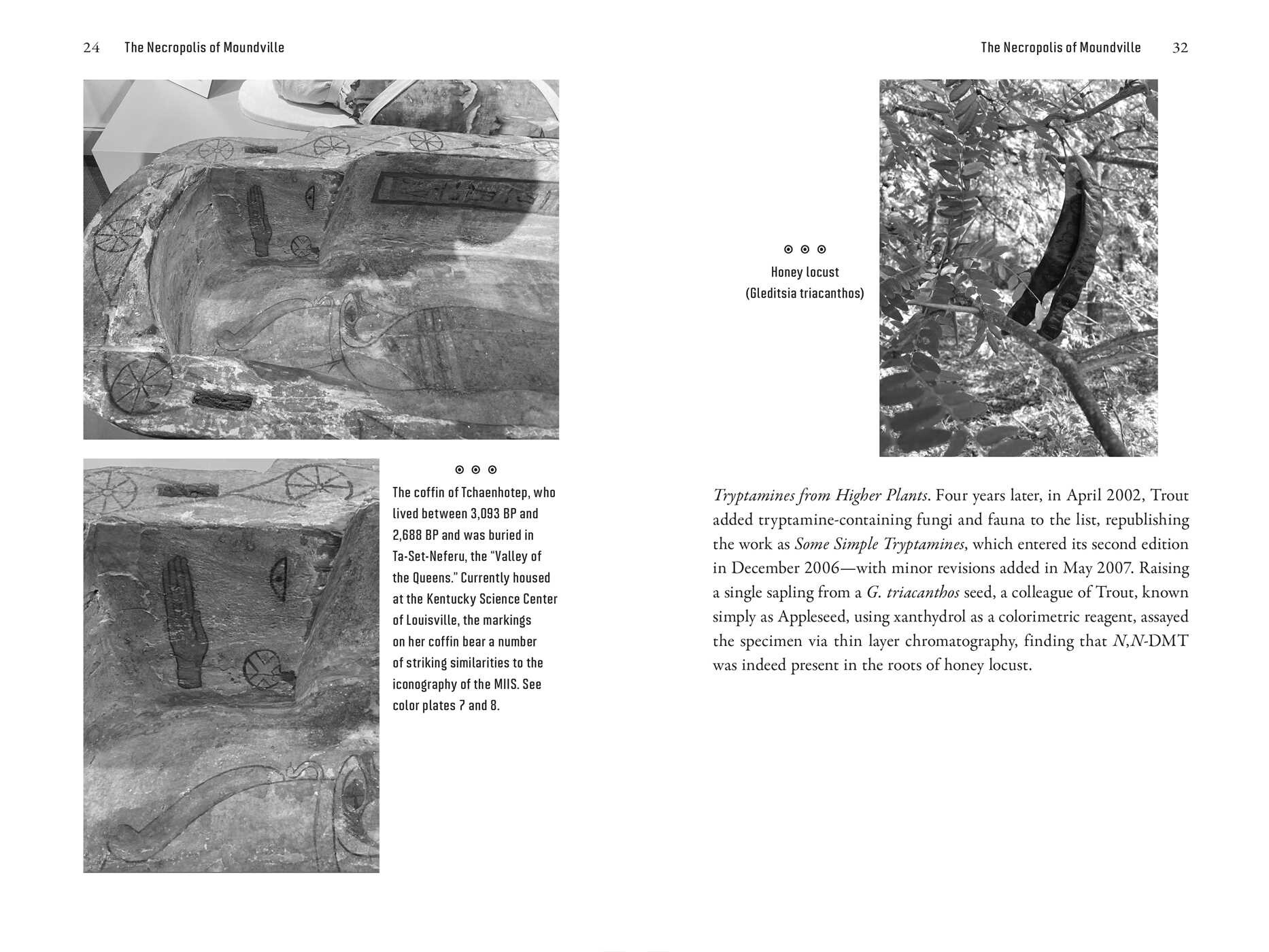

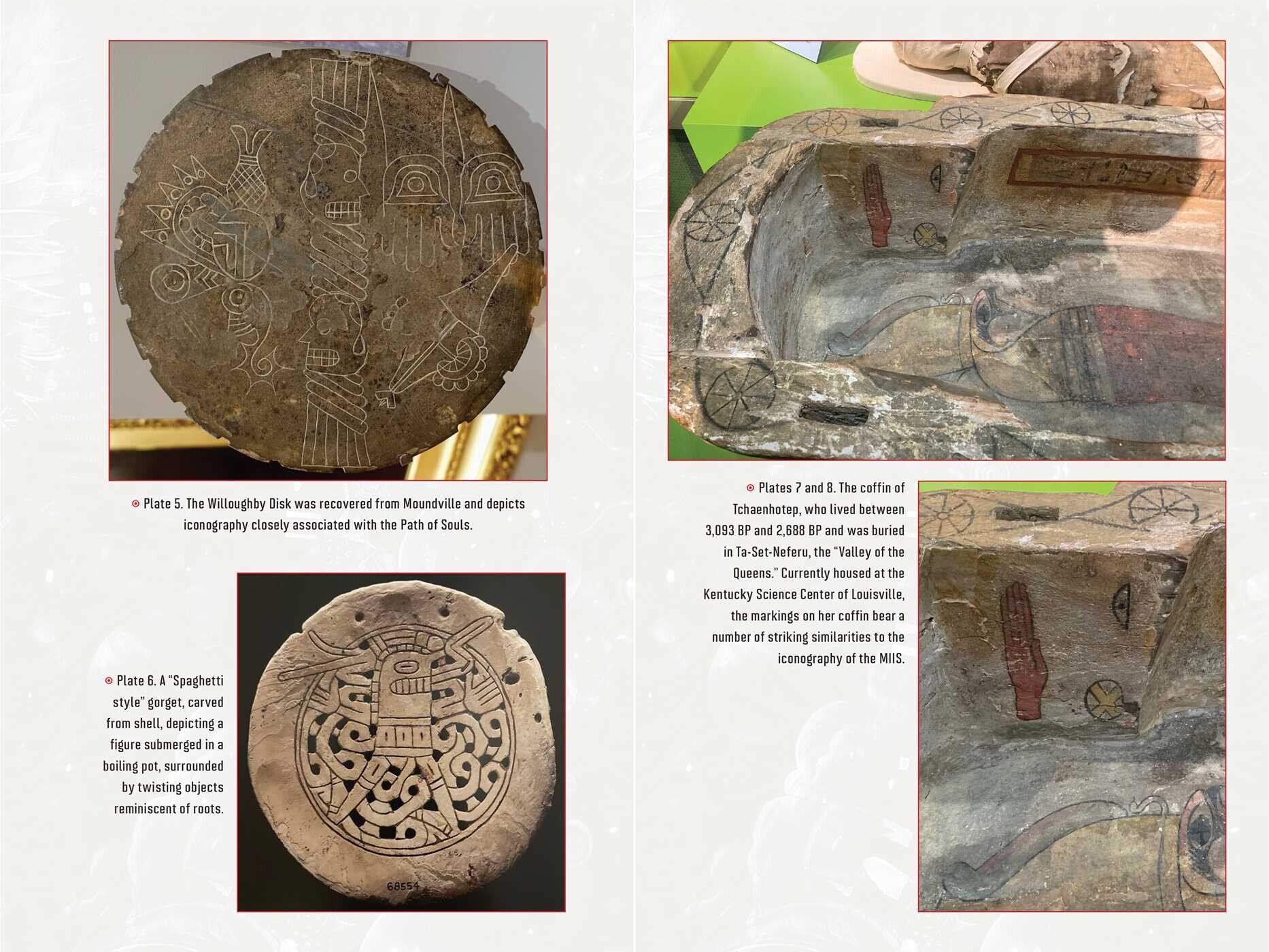

Examining the role of psychoactive plants in afterlife traditions, sacred rituals, and spirit journeying by shamans of the Mississippian mound cultures, P. D. Newman explores in depth the Native American death journey known as the "Trail of Ghosts" or "Path of Souls." He demonstrates how practices such as fasting and trancework when used with psychedelic plants like jimsonweed, black nightshade, morning glory, and amanita and psilocybin mushrooms could evoke the liminal state between life and death in initiatory rites and spirit journeys for shamans and chiefs. He explores the earthwork and platform mounds built by Indigenous cultures of the Mississippi Valley, showing how they quite likely served as early models for the Path of Souls. He also explores similarities between the Ghost Trail afterlife journey and the well-known Egyptian and Tibetan Books of the Dead.

Excerpt

NATIVE AMERICAN INTOXICANTS

While its utilization in the Americas stretches back deep into the opaque mists of prehistory, tobacco use was first documented in the late fifteenth century CE, with Christopher Columbus’s fateful arrival on the beaches of the American continent. Observing its usage among the Taino Arawak tribe of modern-day Florida and the Caribbean, who would send their prayers aloft upon exhaled clouds of malty Nicotiana rustica smoke, the Italian explorer procured samples of tobacco, which returned with him to Spanish shores. It wouldn’t be long before tobacco pipes, cigars, chews, and snuffs would begin showing up in virtually every major European market. However, where Indigenous Americans, by an ancient safeguard of ritual and myth, were largely insulated from the very real potential of its negative effects, European enthusiasts’ uninhibited, chronic consumption and abuse of this new, exotic drug were enough to obscure any sense of the sacred, which tobacco at one time possessed. Long before the arrival of the Spanish and French, though, many Native American tribes told origin stories in regard to tobacco. But among the Amerindians of the Eastern Woodlands, there appears to have been but a single surviving, legendary tale. In his important book, Native American Legends of the Southeast, Lankford—who perhaps more than any other academic has labored for the preservation and understanding of Southeastern Native American cultures—relayed the Yuchi variation of this timeworn tale. A man and a woman went into the woods. The man had intercourse with the woman and the semen fell upon the ground. From that time they separated, each going his own way. But after a while the woman passed near the place again, and thinking to revisit the spot, went there and beheld some strange weeds growing upon it. She watched them a long while. Soon she met the man who had been with her, and said to him, "Let us go to the place and I will show you something beautiful." They went there and saw it. She asked him what name to call the weeds, and he asked her what name she would give them. But neither of them would give a name. Now the woman had a fatherless boy, and she went and told the boy that she had something beautiful. She said, "Let us go and see it."

When they arrived at the place she said to him, "This is the thing that I was telling you about." And the boy at once began to examine it. After a little while he said, "I’m going to name this." Then he named it "tobacco." He pulled up some of the weeds and carried them home carefully and planted them in a selected place. He nursed the plants and they grew and became ripe. Now they had a good odor and the boy began to chew the leaves. He found them very good, and in order to preserve the plants he saved the seeds when they were ripe. He showed the rest of the people how to use the tobacco, and from the seeds which he preserved, all got plants and raised the tobacco for themselves.1

Tobacco is believed to be one of the first plants used by New World shamans to initiate ecstatic trance.2 The charter cited above only mentions chewing the substance. There are a number of modes of consuming tobacco, however, that do not involve chewing, such as eating or drinking, insufflating, applying it topically in the form of salves or poultices, through an enema, and so on—although German anthropologist Johannes Wilbert found that of the 300 South American groups he studied who used tobacco, 233 of them felt that smoking was the most effective—and the most preferred—method of use.3

Indigenous tobacco, which is several times more potent than commercial tobacco, could also be used by shamans for the purpose of communicating with spirits and with the Land of the Dead, even transporting the seer himself into the delirious domain of the deceased. Truly, ingesting excessive quantities of nicotine can actually cause the heart rate to lower to such a degree that a pulse becomes virtually indetectable. This results in critical catatonia and ultimately in a somatic rigidity that simulates the effects of rigor mortis. For all practical purposes, the tobacco-intoxicated shaman appears as though he were dead, during which spell his spirit is understood to have quite literally vacated his lifeless body.4 Moreover, this induced death-state was not always simulated but was actually "an ever-present threat" when visiting that great realm.5 In less extreme cases, unlike common commercial cigarettes, chew, or skoal, varieties of tobacco like Nicotiana rustica and Nicotiana obtusifolia, at correctly regulated dosages, completely wipe out the optical color system in humans, resulting in haunting, ghostlike visuals, where everything one looks upon appears only in black, white, and dingy yellow hues.6 Beyond a simple recreational drug, tobacco was universally hailed among Native American tribes as a medicine, an apotropaic, an offering, a mode of shamanic flight, and even as an essential eans of prayer. It is needed, for example, to begin an official "Half Moon" peyote ceremony.7

As with tobacco, the historical usage among Native Americans of the Lophophora williamsii cactus (formerly Anhalonium lewinii), better known by its Nahuatl name, peyōtl—literally meaning "caterpillar cocoon" —is assuredly archaic, but that makes it no less unknown to us. White men’s knowledge of the Amerindian application of this so-called whiskey root8 doesn’t begin until the end of the nineteenth century, when a Norwegian ethnographer named Carl Lumholtz went off in search of the descendants of the original Puebloan people.9 What he finally found, tucked away in the most inaccessible canyons of the Sierra Madre, was a reclusive tribe of devout cactophiles calling themselves the Tarahumara. Making sheep or goat sacrifices to the visionary cactus, burning costly copal resin while in its presence, the Tarahumara worshipped hikuli (peyote) as a deity, praising it for its "beautiful intoxication."

Lumholtz also encountered hikuritamete or "peyote hunters" from the nearby Huichol or Wixarika tribe. For the Huichol, the peyote cactus, along with cevidae (deer) and maize, occupies a hypostatic position in a Southwestern answer to the Holy Trinity. This tribal trio forms the tripartite backbone of Huichol ritual and belief, and without any one of those three constituents, the other two would surely disappear, too. For without shedding the blood of the deer, the sun will not cause the maize to grow. But things must be done in the right order. It is imperative that the deer should not be offered prior to the peyote hunt. Moreover, the ceremony of parching the maize (similar to the preparation of popcorn), which is believed to bring the rains necessary to produce the next crop, cannot be held without the presence of hikuri. And the hikuri mustn’t be harvested until after the maize has been purged and sanctified.10 These three supports form an indivisible complex on which the entire Huichol way of life is balanced. Donning colorful ceremonial attire, temporarily adopting a special liturgical language, the Huichol would trek over two thousand kilometers, year after year, into the mesas found high above Real de Catorce and onto the holy hunting ground known as Wirikuta. Once there, entering what Romanian historian of religion Mircea Eliade referred to as in illo tempore (mythical time), the Wixarika would reenact the myth of hikuri and el Venado azul—the sacred blue deer, named Kauyumari—whose magical self-sacrifice brought peyote to the people.

The elderly told us that long time ago, high in the Huichol mountains, the grandparents reunited to discuss about their situation. Their people was sick, there was no water or food, it wasn’t raining and land was dry. They decided to send four young men hunting, with the mission of bringing back any food that they were able to obtain to share them with the community, it didn’t matter if it was little or a lot . . .

Next morning, the young men started their journey, each one of them armed with their bow and arrows. They walked for days, until one afternoon, something jumped behind the bushes, it was a big fat deer. The young men were exhausted and hungry, but when they saw the deer, they forgot about everything and started running after it. The deer looked at them and felt compassion. He left them rest that night and next morning prompted to continue the hunting.

Many weeks passed by before arriving to Wirikuta . . . When the young men were walking on the hill, near the Narices hill, they saw the deer jumping in direction of where the Earth Spirit lives. They could swear they saw the deer running in that direction, and tried to find him without success. Suddenly, one of the men shot an arrow that fell inside a deer figure formed by peyote plants, that under the sun, they shined like emeralds do.

Product Details

- Publisher: Inner Traditions (March 4, 2025)

- Length: 216 pages

- ISBN13: 9798888500422

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“In his latest work, P. D. Newman builds upon his literary legacy into the domain of the ancient use of magical plant medicines in southeastern North America. A disciplined and visionary scholar, Newman ties the oral traditions and cosmologies of Indigenous peoples to carefully researched evidence of the use of mystical substances at sacred geographic sites. Newman has uncovered a secret connection between entheogenic and medicinal plants and the inspiration behind Mississippian iconography and cosmology. Indigenous spiritualists consumed these sacred medicines and looked to the cosmos to tell the story of the first humans, the Tree of Life, and the epic tales of the Thunder Twins—among many other mythological motifs. P. D. Newman raises the bar for Indigenous anthropologists and archaeologists to higher levels of thought regarding the formation and function of cosmology in ancient Native America.”

– Taylor Keen (Omaha/Cherokee), author of Rediscovering Turtle Island

“P. D. Newman has written a remarkable and authoritative book that dramatically alters what we have long believed about Native American shamanism. He has masterfully uncovered and documented key aspects of the rituals involved in what is called the ‘Path of Souls’—the journey of the souls of the departed to the sky world and beyond. For those interested in the practices and beliefs of Native American mound builders, this is a must-read book that answers long-concealed mysteries.”

– Gregory L. Little, author of The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Native American Indian Mounds & Earthwo

“P. D. Newman has produced a book with a rare and elusive combination of qualities: engaging, intellectually stimulating, and benefiting from sound scholarship and personal experience. His reconstruction of the interface between psychedelics and shamanic afterlife journeys among the Indigenous peoples of the Mississippi Valley is both inventive and original.”

– Gregory Shushan, Ph.D., author of Near-Death Experience in Ancient Civilizations

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Tripping the Trail of Ghosts eBook 9798888500422