Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

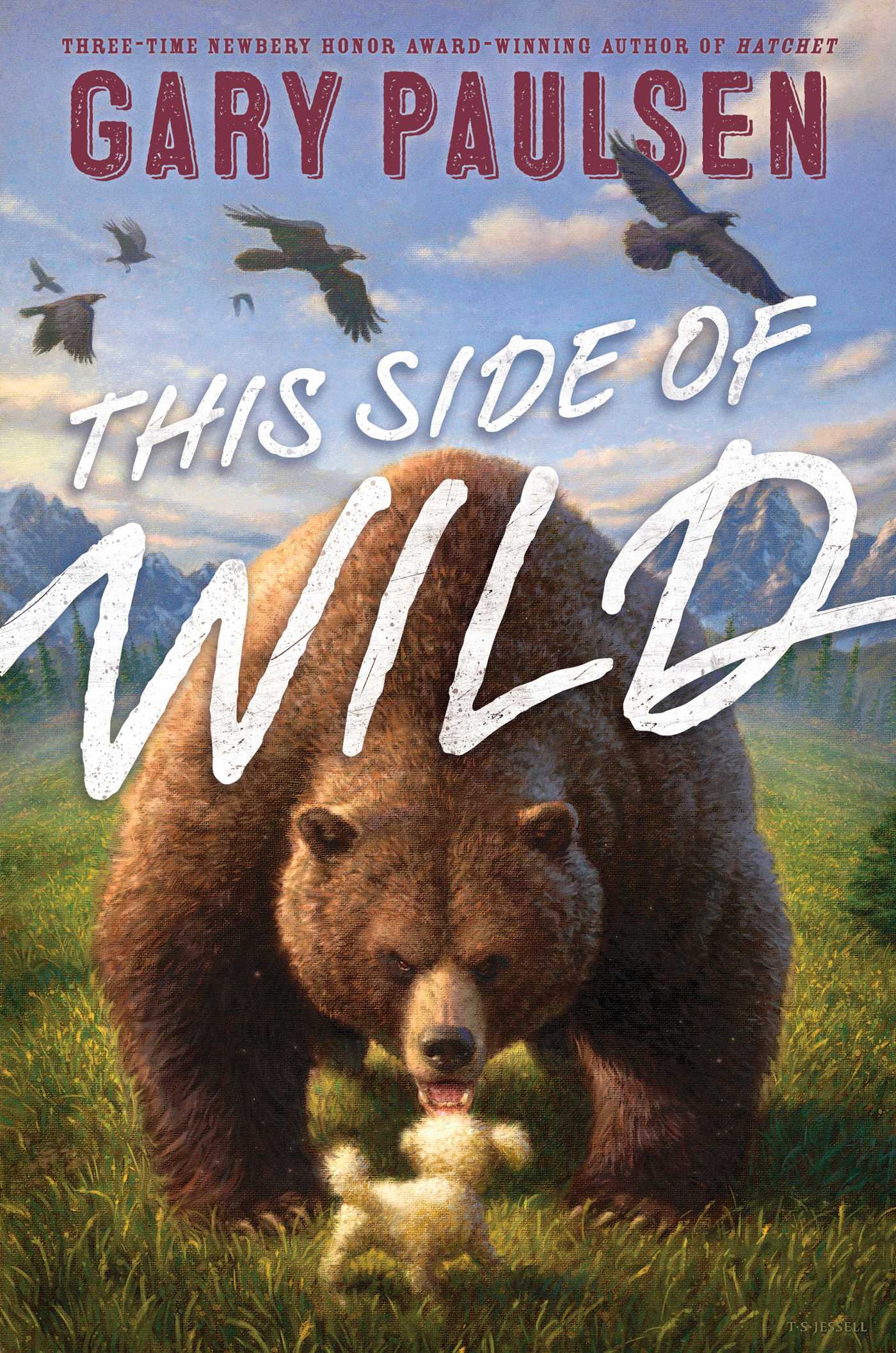

In the National Book Award longlist book This Side of Wild, Newbery Honor–winning author Gary Paulsen shares surprising true stories about his relationship with animals, highlighting their compassion, intellect, intuition, and sense of adventure.

Gary Paulsen is an adventurer who competed in two Iditarods, survived the Minnesota wilderness, and climbed the Bighorns. None of this would have been possible without his truest companions: his animals. Sled dogs rescued him in Alaska, a sickened poodle guarded his well-being, and a horse led him across a desert. Through his interactions with dogs, horses, birds, and more, Gary has been struck with the belief that animals know more than we may fathom.

His understanding and admiration of animals is well known, and in This Side of Wild, which has taken a lifetime to write, he proves the ways in which they have taught him to be a better person.

Gary Paulsen is an adventurer who competed in two Iditarods, survived the Minnesota wilderness, and climbed the Bighorns. None of this would have been possible without his truest companions: his animals. Sled dogs rescued him in Alaska, a sickened poodle guarded his well-being, and a horse led him across a desert. Through his interactions with dogs, horses, birds, and more, Gary has been struck with the belief that animals know more than we may fathom.

His understanding and admiration of animals is well known, and in This Side of Wild, which has taken a lifetime to write, he proves the ways in which they have taught him to be a better person.

Excerpt

This Side of Wild • CHAPTER ONE • A Confusion of Horses, a Border Collie named Josh, a Grizzly Bear Who Liked Holes, and a Poodle with Three Teeth

First, a hugely diversionary trail:

Very few paths are completely direct, and this one seemed at first to be almost insanely devious.

The doctor diagnosed various problems, some lethal, all apparently debilitating, and left me taking various medications and endless rituals of check-ins and checkouts and tests and retests. . . .

Which drove me almost directly away from the whole process. I moved first to Wyoming, a small town called Story, near Sheridan, where I kept staring at the beauty of the Bighorn Mountains, accessed by a trail out of Story, and at last succumbed to the idea of two horses, one for riding and one for packing.

The reasoning was this: I simply could not stand what I had become—stale, perhaps, or stalemated by what appeared to be my faltering body. Clearly I could not hike the Bighorns, or at least I thought I could not (hiking, in any case, was something I had come to dislike—hate—courtesy of the army), and so to horses.

My experience with riding horses was most decidedly limited. As a child on farms in northern Minnesota, I had worked with workhorse teams—mowing and raking hay, cleaning barns with crude sleds and manure forks—and in the summer we would sometimes ride these workhorses.

They were great, massive (weighing more than a ton), gentle animals and so huge that to get on their backs we either had to climb their legs—like shinnying up a living, hair-covered tree—or get them to stand near a board fence or the side of a hayrack (a wagon with tall wheels and a flatbed used for hauling hay from the field to the barn) so we could jump up and over onto their backs.

Once we were on their backs, with a frantic kicking of bare heels and amateur screaming of what we thought were correct-sounding obscenities—mimicked from our elders—and goading, they could sometimes be persuaded to plod slowly across the pasture while we sat and pretended to be Gene Autry or Roy Rogers—childhood cowboy heroes who never shot to kill but always neatly shot the guns from the bad guys’ hands and never kissed the damsels but rode off into the sunset at the end of the story. We would ride down villains who robbed stagecoaches or in other ways threatened damsels in distress, whom we could save and, of course, never kiss, but ride off at the end of our imagination.

The horses were—always—gentle and well behaved, and while they looked nothing like Champion or Trigger—Gene’s and Roy’s wonderful, pampered, combed, and shampooed lightning steeds (Champ was a bay, a golden brown, as I remember it, and Trigger was a palomino, with a blond, flowing mane and tail)—we were transformed into cowboys. With our crude, wood-carved six-guns and battered straw garden hats held on with pieces of twine, imagined with defined clarity that the pasture easily became the far Western range and every bush hid a marauding stage robber or a crafty rustler bent on stealing the poor rancher (my uncle, the farmer) blind.

Oh, it was not always so smooth. While they were wonderfully gentle and easy-minded, they had rules, and when those rules were broken, sometimes their retaliation was complete and devastating. On Saturday nights we went to the nearby town—a series of wood-framed small buildings, all without running water or electricity—wherein lived seventy or eighty people. There was a church there and a saloon, and in back of the saloon an added-on frame shack building with a tattered movie screen and a battery-operated small film projector. They showed the same Gene Autry film all the time, and in this film, Gene jumped out of the second story of a building onto the back of a waiting horse.

We, of course, had to try it, and I held the horse—or tried to—while my friend jumped from the hayloft opening in the barn onto the horse’s waiting back.

He bounced once—his groin virtually destroyed—made a sound like a broken water pump, slid down the horse’s leg, and was kicked in a flat trajectory straight to the rear through the slatted-board wall of the barn. He lived, though I still don’t quite know how; his flying body literally knocked the boards from the wall.

I personally went the way of the Native Americans and made a bow of dried willow, with arrows of river cane sharpened to needlepoints and fletched crudely with tied-on chicken feathers plucked from the much-offended egg layers in the coop, which I used to hunt “buffalo” off the back of Old Jim.

Just exactly where it went wrong we weren’t sure, but I’m fairly certain that nobody had ever shot an arrow from Old Jim’s back before. And I’m absolutely positive that no one had shot said arrow so that the feathers brushed his ears on the way past.

The “buffalo” was a hummock of black dirt directly in front of Jim, and while I couldn’t get him into a run, or even a trot, no matter what I tried, I’m sure he was moving at a relatively fast walk when I drew my mighty willow bow and sent the cane shaft at the pile of dirt.

Just for the record, and no matter what my relatives might say, I did not hit the horse in the back of his head.

Instead the arrow went directly between Jim’s ears, so low the chicken feathers brushed the top of his head as they whistled past.

The effect was immediate and catastrophic. Old Jim somehow gave a mighty one-ton shrug so that all his enormous strength seemed to be focused on squirting me straight into the air like a pumpkin seed, and I fell, somersaulting in a shower of cane arrows and the bow, with a shattering scream on my part and hysterical laughter on the part of the boy with me.

“You looked like a flying porcupine!” he yelled. “Stickers going everywhere . . . You was lucky you wasn’t umpaled.”

Which was largely true and seemed to establish the modus operandi for the rest of my horse-riding life. I do know that I couldn’t get close to Old Jim if I had anything that even remotely resembled a stick for the rest of that summer.

Horses are unique in many ways, though—and I know there will be wild disagreement here—not as smart as dogs, certainly when it comes to math.

I knew nothing of them then and perhaps little more now. But one of those summers I experimented with rodeo.

I was not good at it, to say the very least, and for me it was a particularly stupid thing to do because I was indeed so incredibly bad at it, and I did not do it for any length of time.

I tried bareback bronc riding for a few weeks. I learned some things: I learned intimately how the dirt in Montana tasted and learned that next to old combat veteran infantry sergeants, rodeo riders are the toughest (and kindest and most helpful) people on earth.

But I learned absolutely nothing about horses. I rarely made a good ride, a full ride, but even if I had, you cannot learn much in eight seconds on an animal’s back. . . .

And so to the Bighorn Mountains.

• • •

It is probably true that all mountains are beautiful; there is something about them, the quality of bigness, of an ethereal joy to their size and scenic quality. And I have seen mountain ranges in Canada, the United States, particularly Alaska, have run sled dogs in them and through them and over them and have been immersed in their beauty as with the old Navajo prayer:

Beauty behind me

Beauty before me

Beauty to my left

Beauty to my right

All around me is beauty.

But there is something special about the Bighorns in Wyoming.

I found a small house at the base of a dirt track called the Penrose Trail, which led directly up out of the town of Story into the lower peaks and a huge hay meadow called Penrose Park.

If memory serves, it is twenty or so miles from Story up to the meadow, then a few more miles to an old cabin on a lake and the beginning of a wilderness trail through staggering beauty; the trail is called the Solitude Trail—among other nicknames—and it wanders through some seventy miles of mountains in a large loop.

Older people who lived in Story, who rode the mountains before there were trails, told me of the beauty in the high country, and it became at first a lure, a pull, and then almost a drive.

I wanted to see the country, the high country, as I had seen it in Alaska with dog teams; the problem here was that it was summer, too hot for dogs, the distances were much too great, and my dislike of hiking much too sincere for me to even consider backpacking through the mountains.

And so, to horse.

Unfortunately, I knew little or nothing as to how one goes about acquiring a horse to ride on potentially dangerous mountain trails.

And then another horse to pack gear on those same possibly dangerous mountain trails.

For those who have read of my trials and tribulations when I tried to learn how to run dogs for the Iditarod, you will note a great many similarities in the learning procedure, or more accurately, how the learning processes for both endeavors strongly resembled a train wreck. It is true that I have for most of my life lived beneath the military concept that “there is absolutely no substitute for personal inspection at zero altitude” when it comes to trying to learn something. While functional, the problem with this theory is that it often places you personally and physically at the very nexus of destruction. Hence both legs broken, both arms broken more than once, wrists broken, teeth knocked out, ribs cracked and broken, both thumbs broken more than once (strangely more painful than the other breaks) and—seemingly impossible—an arrow self-driven through my left thumb.

Among other bits of lesser mayhem . . .

I had read many Westerns, of course, doing research, and had even written several, had indeed won the Spur Award from the Western Writers of America three times for Western novels. This is perhaps indicative of excess glibness, considering how little I apparently knew. But I had read all those books and seen God knows how many Western films and knew that people had used packhorses. I had run two Iditarod sled-dog races across Alaska, and I thought—really, it seemed to be that simple—that if a person could do one, he could do the other.

The problem was that I did not know anyone involved with horses and so—as God is my witness—I went to the yellow pages for Sheridan, Wyoming (the nearest town of any size), looked under “horse,” and near the end of the section, found a listing of horse brokers. (This was before there was a viable Internet to use.)

Perfect, I thought. There were people who bought and sold horses—exactly what I needed. The first two names I called were not available, but on the third call, a gruff voice answered with a word that sounded like “haaawdy” and then asked, “Whut due ya’ll need . . . ?”

“It’s simple, really,” I answered. “I need two horses. One to ride, one to carry a pack. I want to go up into the Bighorn Mountains. . . .”

“Why, sure you do.” There was a pause, a long pause. I would surmise later, when I knew more of horse brokers, that he either thought I was joking, or, if he were very lucky, that I was uncompromisingly green, bordering on being perhaps medically stupid, and he had a chance to make his profit for the year on a one- or two-horse deal.

It was, of course, closer to the latter.

“Where do you live?” he asked.

“Story.” I named the small town at the base of the Bighorns, near where the Penrose Trail comes out, or down and out. I had purchased a small house there with a few acres of thick grass, and I was surprised to find it vacant. I was to find later—and there were so many “laters” when dealing with Wyoming—near the end of October, why this was to be, when the first late-October snow, a crushing thirty-two inches, came in one day, followed two days later by another thirty inches.

But back then I was wonderfully innocent; it was a grand summer day and the mountains beckoned, pulled, demanded that I come to them as I had in winter in Alaska with dogs during the Iditarod. “Where should I come?” I asked.

“No,” he said quickly. “I’ll come to you with the horses. I have two that are perfect for you.”

“Well, let me . . .” I was going to say, “Let me get ready for them,” as I had no idea what one did, really, to have and keep horses. The property had a small pasture with two feet of grass and a three-sided shed, was surrounded by tall ponderosa pines for shade and little else.

But he hung up before I could get another word out, and it seemed that I had just turned around when a large, gaudy pickup hooked to a flashy two-horse trailer pulled into the driveway. It’s difficult to describe it without lapsing into poor taste; indeed, the truck and trailer alone were a monument to the word “god-awful.” The color was an eye-ripping red with black rubber mudguards, and on each mudguard was a chrome silhouette of a nude woman, and across the front of the hood was—I swear—an actual six-foot-wide longhorn mounted in a silver boss with an engraving (again, I couldn’t make this up) of another nude woman with impossibly large features, which was, in turn, matched by the mudguards on the trailer and a large painted silhouette of a nude on the front of the trailer cleverly positioned so that a small ventilation opening for the horses to put their heads out . . . Well, you get the picture.

And if the truck and trailer were in bad taste, they were nothing compared to the man. Tall but with a large beer belly covered by an enormous silver and gold belt buckle with RODEO engraved over yet another silhouette of a nude woman, on top of tailor-cut jeans tucked inside knee-high white cowboys boots with (a major change in art forms) a bright blue bald eagle stitched on the front.

On his head was an impossibly large cowboy hat with a silver hatband, which I at first thought was made of little conchos but turned out to be little silhouettes of, right . . . more women.

He shook my hand without speaking, turned and opened the back of the trailer, and let two horses step out at the same time, which meant they weren’t tied in, nor did they have butt chains on—two major mistakes that prove he knew little about trailering horses and hence little about horses themselves.

Not that it mattered. I had already made up my mind that looking in the yellow pages cold for a horse broker was Very Wrong and that I wouldn’t buy a horse from this guy if he gave them away.

And yet . . .

And yet . . .

A thing happened, something I had never seen before.

The horses were simply standing there, at relative peace—no nervousness at all—and there was something about them that seemed, well, inviting. And I thought, felt, that I should go to them and touch them, pet them. I know how that sounds, and I have never been all “woo-woo” about animals, especially horses, of which I knew little except that they were big, huge, nine hundred to a thousand pounds, and potentially dangerous. Very dangerous. Decidedly so if they were startled or panicked or surprised. At that time I had had two friends killed while riding them and knew of several others permanently in wheelchairs. (This was years before actor Christopher Reeve, who as an excellent, Olympic-level rider, was permanently completely disabled—which led directly to his later death—when falling on a simple training jump.)

I actually took a step toward them—worse, toward their rear ends, which is never the way you walk up on a strange horse—before stopping.

Josh, my border collie, my friend, had been at my side watching, and before I could move farther, he rose from a sitting position, trotted forward, and without hesitating at all, trotted between the back legs of the mare, paused beneath her belly, then continued up through the front legs. At that moment she lowered her head and they touched noses, whereupon Josh turned to the right, touched noses with the black horse, who had lowered his head, trotted between his front legs, paused under the belly, through his back legs, then back in front of me, where he sat, looked up and—I swear—nodded.

Or it seemed that he nodded.

Or he wanted to nod.

Or he wanted me to think that he nodded.

Or he wanted me to know something. Something good about the horses.

What we had witnessed—the broker and I—had been nothing less than a kind of miracle. Dogs, perhaps many dogs, had been killed simply by getting too close to the back feet of a horse. Years later I would acquire a horse who had mistakenly killed his owner, a young woman who was checking his back feet, when a dog came too close. As it kicked at the dog, the horse caught the woman in the chest with a glancing blow. The force was so powerful it severed her aorta and she bled to death before help could arrive.

For Josh to so nonchalantly trot through the mare’s legs, as well as the legs of the black cow pony, then back to me, came in the form of a message. . . .

And I listened.

I had by that time lived with dogs, run with dogs, camped with dogs, for literally thousands and thousands of joyous and not a little educational miles. I had been saved, my life saved, many times by dogs—mainly lead dogs—making decisions about bad ice or moose attacks in the night, and I had learned again and again of my own frailty, slowness of thought and action compared to what the dogs could accomplish. And while at first I had trouble believing, because I was as chauvinistic as most humans are, at last I surrendered my own will and abilities to that of the dogs, and when Josh gave his okay to the horses, I listened and bought the horses no matter my feelings for the broker. And the four of us—horses, dog, and I—spent a wonderful summer exploring the wilderness areas of the Bighorn Mountains in Wyoming.

And through all of it—swimming rivers, climbing impossible ridges and grades, running into bear, moose, and one unforgettable brush with a mountain lion—the horses never once let me down or even gave me a moment’s pause. Indeed, as the summer passed, I came to rely more on them—and their relationship with Josh—than on my own judgment. And the knowledge came that the three of them were actually running things and I was just along for the wonderful ride. Again and again as we went into the mountains I relinquished my feeling of individual, my feeling of self, to the three of them; we would start up the mountain out of the yard, and within a few hundred feet the mare—which I habitually rode, using the little black pony for packing—would take over and run the show. Josh would go out ahead on the trail, and if he ran into anything—a moose or an elk or, less frequently, a bear—he would come back and look at the mare, and she would slow and let me come to attention and react. When the ride got long, as it sometimes did, and Josh grew tired (he ran at least six miles for every mile the horse covered) and there was a long flat area, such as a meadow, he would wait until there was a boulder or nearby hummock and would jump up behind me on the mare and ride for a while, sitting on her rump. When—how—they worked this out, I had no idea. I had never seen it before and never since, with other dogs and horses. But they did it, irrespective of me, and as we rode, the seeds for this book were planted. And as they sprouted and grew with note taking and the mining of my childhood memories came the belief, the solid belief, that it is true not just for me but for all of us.

We don’t own animals. Even those we kill to eat.

We live with them.

We get to live with them.

And so to Corky.

• • •

To shorten what many people have come to think of as a kind of madness—indeed, an earlier book of mine terms it a kind of madness—I decided at the age of sixty-seven to go back to dogs and Alaska and run the Iditarod again.

There are/were many reasons for this decision to run it after a lapse of twenty years, but for people with normal lives they do not seem even remotely logical. In many respects I think it is something on the order of combat; for people who have never experienced it, it is impossible to explain except to say it is outrageous, and for people who have done it, no explanation is necessary.

I missed the dogs.

Terribly.

Every day I thought of them: dogs long gone, old friends passed, and the joy and beauty they gave me.

And I missed the wilds of Alaska, to run through and in them with a dog team, alone and silent in such staggering beauty. When I took a friend of mine from Scotland to Alaskan mountains and rivers and forest—this was an articulate, well-read, educated friend—he could only stand, half crying, and say, “Jesus Christ,” over and over again in a kind of prayer.

All of that. The wild and the dogs and the stunning joy of dancing through the wilderness with them hung over me—no, danced out ahead of me—every single waking minute of every single waking day.

The hard thing to understand is that I ever left it, that I didn’t go back to the dogs sooner. Age didn’t seem to matter; nor did physical condition, though everything crazy you do when you’re young, every bar fight, every rough horse ridden and thrown from, every torturous twist the military does to your body comes back with a kind of staggering vengeance when you get old. Creaking bones, small and large traveling pains, bad vision . . .

And none of it seemed to matter even remotely; the pain became a kind of wonderful recognition that I was still alive, another obstacle to beat or, as the Marines put it, “Pain is weakness leaving the body.” Bushwa, of course, but it was and is that way for me and so I found some sled dogs.

And then more sled dogs.

And still more sled dogs.

And equipment . . .

I bought an old Ford truck with a dog box on it, found a shack in the woods in northern Minnesota, and tried training there. When that didn’t work—way too crowded; I waited at a trail intersection one afternoon while one hundred and four snow machines (at least fifty of them were pulling work sleds loaded with cases of beer) passed in front of my lead dog—I cut, as they say, and ran to Alaska, where I found an ugly old house, a kind of huge suburban shack, back in the bush, and sort of moved in.

“Sort of,” because there were no facilities for sled dogs. Each dog needed a post driven into the ground, with a chain and an insulated house. I could have kept them on a picket chain while I built the kennel—which would take two months; I would have to rent a bulldozer to clear a place, drill holes, build houses, etc. That seemed excessive, to have them confined to short pickets for all that time.

Luckily, a company would take the dogs to Juneau, put them up on the snow/glaciers for the summer to give rides to tourists, feed them whatever food I wanted to feed them, and in general take really good care of them. Plus they would continue to get healthy exercise.

I agreed to it, drove them to Juneau, watched them take helicopter rides up to the glacier—a singular experience for dogs who have never been off the ground—and came back to a house empty of dogs. It was a strange feeling—as if my family were suddenly gone.

I rented a bulldozer and cleared four acres of the small—if ancient—black spruce and set to work. In Wasilla there was a place where good tools could be rented, and I found a kind of machine for drilling four-foot-deep-by-eight-inch-wide holes in the ground. It was not the small auger type, but a large rig on wheels that made an extraordinary amount of noise and slamming motions while it was running so that it required constant attention and it was impossible to see or hear anything else.

And now a brief note on Alaska. Many people say many mistaken things about the state, people who have never lived there, as if it were a kind of Disneyland of the north, with quaintly “cute” animals like wolves, bears, and moose, which seem to have been placed there somehow for photo opportunities. Those are largely people who never truly get off the bus but shoot pictures through the windows.

The truth is Alaska is for real, and with a lack of knowledge, of understanding, this reality comes with sometimes great and sometimes lethal danger. At the time of this writing, a young woman schoolteacher visiting one of the outlying villages went for a jog—which she was accustomed to doing in the Lower 48—and was dragged down, killed, and eaten by wolves. Bears attack frequently—both black bears and grizzlies—as do moose, which can do great damage by kicking. (They are as strong as horses.) I personally know of several people severely injured by moose and four killed and eaten by bears.

When I moved back up to Alaska, I had in a strange way fallen into the category of the ignorant tourist. I had run two Iditarods, it was true, back in l983 and l985, but then I had been just visiting in winter when bears were in hibernation and did not understand or truly know the possibilities of summer attacks by bears.

And I bought a house at the end of a road that terminated on the very edge of a wilderness that stretched for literally thousands of miles. Not a road or village or settlement or power line or even a single person existed in this staggering immensity. Just wild things in the wild.

And I took a bulldozer and cleared four acres and moved in more or less like I owned the place.

Well.

Many things disagreed with me about this so-called ownership. On the first warm day, approximately two hundred million mosquitoes decided to express this disagreement and came to call. Then bears hit my trash, and I think it was a wolverine (there are no skunks in Alaska proper—nor snakes) that sprayed on most of what I had outside. A moose dented the top of my truck hood—I think just to be annoying. It was strange because I was alone—my dog handler being with the dogs on the glacier in Juneau—and I kept feeling as though I was being watched.

And I was.

About halfway through the afternoon of the second day with the heavy boring machine slamming me around, I felt a call from nature and I shut the machine down and went into the house to answer that call. I wasn’t gone fifteen or twenty minutes, but when I came out, I found I was not alone.

The drilling rig had kicked up a pile of soft dirt next to the hole, and there, in that pile of soft dirt, was a single bear track that measured seven and a half inches wide by eleven and a half inches long.

Grizzly.

Easily twice the size of most black bears.

It had been watching me.

Every hair on the back of my neck stood up.

It had stood there, back in the thick trees—not thirty or forty feet away—and watched me drilling holes. As soon as I’d gone into the house, it had come forward to see what I had been doing—to check out the hole—and I hadn’t seen or heard a thing.

I’d had no clue.

The next time, I thought, it could come up behind me while I was running the machine and simply bite my head off. (One of the bear attacks I had heard of ended in just that way—one bite, clean off. Like a guillotine.)

Strangely, it was not the fear of an attack that bothered me as much as the fact that I was alone, some kind of strange dread of that dark band of spruce and that bears, or any other animal, could stand there and watch and I wouldn’t know it.

I needed company. Somebody to watch my back. Somebody to give me at least a small warning.

I needed, really, a dog. And all my sled dogs were gone, up on the glacier for the summer.

And a gun.

I needed a dog for company and a gun—which I did not have—for possible protection. It being so complicated to drive across Canada with firearms, I had left my weapons with my son in Minnesota.

A gun was not a problem. Wasilla had several pawnshops. At one, I purchased a used Mossberg twelve-gauge pump, which held five rounds and had a slightly shortened barrel. I also bought a box of Magnum full-diameter slugs and another box with Magnum double-ought buckshot, fifteen thirty-caliber-round balls per shell, each ball a third of an inch in diameter. Either way, slugs or buckshot, pumping in one after the other, I could pretty much stop a charging Buick.

False security, as we will find later.

As for the dog, I always got my pets at animal shelters, so I called the Wasilla shelter and was told—perfect, really—that they had a three-legged border collie that needed a good home. He would make a great pet and work companion. I had, over the years, saved several border collies and found them to be something just a little better than wonderful—way smarter than me—and I planned for him to stay a house pet after the team came back from the glacier in Juneau.

The rule was first come, first served, and there had been another call on the border collie. So I jumped in my truck and roared the forty miles to Wasilla, then on down near the town of Palmer, slid into the parking lot at the shelter . . .

Just, as it turned out, seven minutes too late.

The other people had come for the border collie. Which was fine—they would give it a good home. I asked the woman at the shelter if she had another dog that might be suitable.

“Well . . . there is one that we just got and can’t afford to keep, since it will need a lot of medical and dental care and we don’t have any money. . . .”

Oh, I thought. Good. Medical bills. “Well, I don’t know. I kind of need one pretty quick. . . .”

“He was scheduled to be put down tomorrow if nobody showed for him.”

Well. She was probably playing me, but that was all right; you do what you have to do to save a dog, and she was hitting the target perfectly. I could not stand to have a dog put down. In a moment of illogical compassion and perhaps some weakness, I said: “All right. Bring him out.”

And so I met Corky. An eight-pound toy poodle covered with abscesses, mouth filled with rotten teeth, one ear and his butt packed with pus. He was probably ten or eleven years old, though the people who dumped him said in a form that he was only six. They also said that the reason they were leaving him was that he was “too rambunctious.”

“What did he do?” I asked as they brought him out in the little kennel the people had left him in. “Rip the tires off the car?” How the hell could such a little thing be “too rambunctious”?

There was no way, I thought, that this dog would be able to save me from grizzlies. . . . He’d be lucky to get home alive, judging by the way he looked.

And yet.

And yet there he was, looking at me through sickened, red eyes, wanting something, wanting me to sign, to acknowledge the contract, the age-old contract between a man and a dog, the contract that says simply, “I will be for you if you will be for me. . . .”

I reached out and took him in my arms, and he screamed in pain, screamed all the way to the truck, then curled up in my lap, whimpering, as I took him to the vet, where he screamed as I carried him into her office and left him.

For three days.

After which, having gone through many procedures for draining abscesses, cleaning out infections, pulling rotten teeth, and going through dental surgery (he wound up with only three teeth, the two forward grippers on the bottom and one—right—canine on top), and after I paid a walloping $1,207.94, I had a “free” watch poodle from the pound.

It just couldn’t be that he would work out. Eight stomping pounds of pure poodle—any big bird could carry him off. He will, I thought, turn out to be a live table ornament, something for the cat (named Hero) to bat around and play with. A toy—and indeed, they called them toy poodles.

However, not only was I wrong, completely wrong—damn near dead wrong—but Corky turned out to be perfect, absolutely perfect for the job.

The thing is, in some way he knew—he knew—what it was all about. I brought him home and decided that except for letting him go outside for the bathroom, I would keep him in the house. The truth is there were great risks for him outdoors. Bald eagles were always about—sometimes as many as four sitting in trees around the house. There were truly enormous owls—one of which nailed a friend’s Pomeranian, carried it off never to be seen again. There were also wolves (I lived on the edge of the famed Talkeetna pack’s territory—in reality a series of smaller roaming packs all stemming from the core pack and covering an area as big as some eastern states), fox, and (I think) coyotes, or something near it. All of them would grab a cat or a poodle—the wolves sometimes taking pets as large as Labs and collies, not to mention livestock and now and then a human.

So when I brought him home, I put him in the house and that first morning went into the cleared area, leaned the shotgun against a big rock, fired up the hole digger, and went to work, thinking, if not a good watch dog, he was still a good friend, and I had, if needed, the shotgun.

Strangely, as noisy and as powerful as the beast of a machine was—it dug an eight-inch-by-four-foot-deep hole in virtually no time at all, kicking my tail all the time—it seemed to be breaking down.

There was a new sound coming from it—a high-pitched, keening whine from a bearing (I thought). I swore. Part of the agreement was that though it was a rental, I was responsible for anything that happened to it while I had possession. When it comes to fixing mechanical things, I fell somewhere into the Complete Idiot level. I stopped the machine, thinking I could at least check the oil (which was my limit of repair).

The whining didn’t stop with the engine and seemed to be coming from somewhere behind me.

I turned to face the house, and there, in the big window on the ground floor—the sill three feet above the floor—was Corky.

He had somehow jumped up to the sill and was on his back legs on the ledge, clawing at the window with his front feet, screaming in that high-pitched ruined- bearing sound I thought had come from the posthole digger machine.

I smiled and thought how sweet it was; he wanted to be outside with me.

I then noticed something I had not seen initially. He was clawing at the window with a true kind of madness; if it were only affection, I thought, he must really love me, way more than he’d indicated when I’d brought him home from the pound.

The second thing hit me at the same moment. He wasn’t looking at me. Instead he was looking off to my right, toward the northwest corner of the cleared area. I turned to see a full-on male grizzly standing just at the edge of the blue spruce, studying me (I thought) like I was a side of beef. I had no idea how long he’d been there—probably as long as the high-pitched whining had been sounding over the bellow of the engine—certainly minutes. Several minutes. And Corky had been trying to warn me.

I knew then very little of bears. I’d heard all the horror stories—many of them true—but I also knew that my neighbor had thrown rocks at a grizzly that was in her garden and it had run off.

I wasn’t about to throw a rock at this guy; he was at least eight hundred pounds and taller than me and would probably take the extra time while killing me to insert the rock . . .

But I didn’t have to worry, I thought. I had the shotgun. The gun made me superior to almost all living things in North America. It was a massive twelve-gauge Magnum. The gun would solve the problem. I would shoot once in the air—which everybody said to do—and the bear would leave. I would jack another shell into it just in case he decided to come at me. Simple, really. I had done the army. I knew how to shoot very well—as well as an expert. There was no real problem.

Here is what I would have liked to have happened. I would swing gracefully, even deftly, one hand swiping the shotgun from the rock, pumping the action with a practiced one-hand motion—the way they show off in movies—and putting a slug in the chamber while clicking the safety off in the same motion. Then I’d swoop the barrel up over the bear, squeeze the trigger . . .

And the truth is it might have been something like that except . . .

First the bear moved. I think he was off balance standing upright. He dropped to all fours and then stood again to gain a new balance. He didn’t come toward me at all, but the sudden motion startled me—I might say frightened me—so that I turned too fast and fell flat on my face, my hand outstretched for the shotgun, which I accidently knocked off the rock out of reach.

I scrabbled to my hands and knees—and “scrabbled” is the right word, like a great crab. Somehow I got to the shotgun, and with something between groping and grasping, I managed to get the thing pointed in the general direction of the bear, but way high—I didn’t want to hit him. I worked the pump frantically, so that two rounds ejected out and onto the ground unfired. I aimed still higher and squeezed the trigger.

Click.

An awful sound. I double-checked the safety. It was off. I worked the pump again, recocked the piece, calmer now, the bear looking at me with more interest, aimed off to the right of the bear with more care now and squeezed the trigger.

Click.

I felt this wave of soft nausea pass over me. I wasn’t really terrified. The bear still stood there; it wasn’t charging. Corky was still clawing at the window. In fact, I was relatively calm, although, as I’ve had happen before in life, several of the glands in my body were beginning to send more and more urgent signals; there was a copper taste in my mouth and definite poop-and-flee information going from my brain to my bottom.

I stood slowly and without making eye contact—not a problem as the bear was still almost fifty yards away—and moved slowly toward the back door of the house.

The bear dropped to all fours—stopping my breath momentarily and nearly stopping my heart—made a loud “whuffing” sound, then turned and disappeared into the woods.

Rule one, I thought. The temperature was cool, but I was covered in sweat, my hands shaking. Rule one: Always test fire a new weapon, no matter how proficient you might think you are.

And rule two: Listen to the poodle.

I went into the house, where Corky greeted me, still in that wonderful high-pitched scream, and we sat for a time in a big chair, Corky in my lap, me petting him and telling him that even with me spending more than a thousand dollars on him, he had been a wonderful buy.

And again he knew. He knew what he had done and what his job was, and with each day his work evolved more and more.

From that day forward, for the rest of the summer, we were inseparable. I would awaken at four in the morning, have a bowl of oatmeal, and give Corky his breakfast of raw meat (I had learned years earlier that the best dog food in the world was plain, raw hamburger, no matter the breed), and we would go to work. I bought a new shotgun, which I always kept at hand, and the Walmart in Wasilla started carrying an anti-bear spray that was very effective, which I carried in a holster on my belt.

Corky sat at my side, no matter where I worked, watching the surrounding spruce forest, and if anything moved—anything, a branch, a leaf, a limb—he started the keening sound and I would stop what I was doing and investigate where he looked and always, always there was something.

A breeze, a squirrel, a fox, a grouse with chicks, a wolf, a moose, another squirrel, dozens of squirrels, a marten, a porcupine, several bears, more moose, once a wolverine . . . always something.

He was like an early-warning radar, always on guard, always alert, and if that was all he did—watch the forest when I was outside—it would have been enough. With practice, I quickly came to believe him, to trust him and his judgment.

But he expanded his duties constantly. At first he was a guard dog—all eight pounds, well, nine and finally ten when the raw meat kicked in—and then he began to make judgment calls as well. A grouse would take a softer sound than, say, a bear, and in the end a squirrel would be only a whimper while a moose or bear would be an outright bark, with a grizzly bear bringing the loudest bark/scream/whine of all.

I came to depend even more on his knowledge and judgment, to the point that he was no longer my dog, my pet, but we were equals, and finally, as it had been with Josh and the mare, we were not equals any longer but he was above me in some way, able to see what I could not, hear what I could not. We would start out in the morning and I would hesitate at the door, let him out first to look around the yard for a moment, pee on the porch post, declaim the day as useful and safe, and then we would move into it.

And still it grew.

I was sitting at the table one day, having a cup of tea with a friend, Corky sleeping in my lap. The friend had left something he wanted to show me out in his truck and he suddenly stood to walk around me to the door to bring it in. As he moved behind me, Corky awakened, stood on my lap, bared his two lower and one upper-right tooth (a god-awful grotesque look, as if trying to do an Elvis Presley impersonation), and uttered what, for Corky, was a very threatening growl. Considering that Corky knew this friend, loved this friend, had earlier been asleep in this friend’s own lap, the growl was surprising, to say the least.

“It’s your back,” he said. “He doesn’t want anybody behind you. . . .”

And that was it. A new criteria to his job—“watch my six,” as fighter pilots would put it. Nobody could be behind me without a warning. Not even a friend.

“Thank God he doesn’t have opposing thumbs,” my friend said. “He’d get a gun and God knows how many people he’d shoot just for walking behind you. . . .”

The thing is, he’s not an angry or yappy dog. He loves people, greets them with all the tail wags possible, licks their faces. Absolutely adores children. He’s just a loving and sweet dog.

But he’s got these rules. His own rules for guarding me, handling me, taking care of me. We are friends. We love each other. He sleeps in bed with me in the crook of my knees, but I am more as well. I am the job.

Two more bits of information on Corky. Studies have been done on mirrors and animals, and it has been decided that only primates understand the concept of reflection in a mirror. Even other monkeys don’t realize that they’re looking at themselves in the reflection.

We have an old 1996 Ford dog truck, which we use for hauling sled dogs. The box in back makes it impossible to see out the back window. But there are large side rearview mirrors, and Corky watches in the mirrors. When somebody comes up from the rear to pass us, he growls. They’re on our six. He reads the mirrors. And nobody, but nobody, gets on our six without a warning, because he is, and knows he is, after all, the Corkinator. . . .

One further note: The sled dogs came back from the glacier in late September, still before snow, and moved in and peed in their circles and in a wonderful way changed the dynamic of everything. There was glad noise, songs, snarls, and joy, and Corky decided he did not need to patrol the yard from the windows in the house as much as he had. Also, the pandemonium of the kennel scared away the eagles (only for a short time and then they came back with a vengeance, along with thirty ravens—more on this in later chapters), so we could let Corky out in the yard by the house without worrying about air attacks except from owls, which usually hit only at night.

Because of the clamor, he would stay away from the sled dogs. . . .

Or so we thought.

And for a couple of weeks it seemed to be working that way. Because there was no snow, we pulled a four-wheeler with three sixteen-dog teams, strengthening them and training leaders, Corky watching from the windows as we ripped out of the kennel and into the trail system.

Everything seemed to have settled in. There was a bit of extra noise when the sled dogs saw me let Corky out for a few minutes to (I thought) mark the porch posts. I left him there on the front porch in the dark as I went in and started coffee and some bacon for sandwiches, and when I came back to the door, Corky would be sitting there waiting, would come into the house to sit on the windowsill, watch us harness and leave.

The perfect house dog.

Then we got a new inch of snow and I could see tracks, and I found that Corky had hidden issues.

I thought he was peeing on and marking the porch. Dead wrong. His ego was much too substantial for such limited territory. His little poodle tracks—remember, he weighed between eight and ten pounds and most of the sled dogs clocked in at fifty or so—trotted past the porch posts, out around the house directly up to the lead dog position in the kennel (there were two female leaders and one male), and he claimed them, peeing on the edges of their circles, which lit them up, set them to lunging and snarling at him.

He owned them—that’s what he was saying with his actions. You’re mine. Then, dividing the kennel into four more sections, he marked five more places, essentially claiming ownership and leadership over the entire kennel: all eight romping stomping pounds of him. Grizzlies, sled dogs, people—it didn’t matter. He owned them all. He simply had no fear.

Then back to the house, touching up the porch post as he came to the door, up the steps, to sit, waiting for me to let him in for breakfast.

We feed pure meat to the sled dogs—well, all dogs, as far as that goes, cut-up chunks of bloody beef heart. And the smell went out and out into the surrounding forest, and drawn by the smell, the eagles came back, started trying to steal it from the sled dogs. Some of their passes and strikes came close to Corky, so we retired him to New Mexico, where I have a shack in the mountains.

I am sitting there now, writing this, and Corky is with me. He is older now, his hearing dampened a bit, his eyes dimming a little, but yesterday I was sitting writing and a flock of wild turkeys (I think about twenty of them) came up onto the back porch, looking for scraps, and Corky hit the glass of the back door like a snarling banshee, shoulder hair up, three teeth bared in slavering-spit Elvis grimace, and he scared them away in a showering storm of turkey poop and blown wing feathers.

My six is still covered.

First, a hugely diversionary trail:

Very few paths are completely direct, and this one seemed at first to be almost insanely devious.

The doctor diagnosed various problems, some lethal, all apparently debilitating, and left me taking various medications and endless rituals of check-ins and checkouts and tests and retests. . . .

Which drove me almost directly away from the whole process. I moved first to Wyoming, a small town called Story, near Sheridan, where I kept staring at the beauty of the Bighorn Mountains, accessed by a trail out of Story, and at last succumbed to the idea of two horses, one for riding and one for packing.

The reasoning was this: I simply could not stand what I had become—stale, perhaps, or stalemated by what appeared to be my faltering body. Clearly I could not hike the Bighorns, or at least I thought I could not (hiking, in any case, was something I had come to dislike—hate—courtesy of the army), and so to horses.

My experience with riding horses was most decidedly limited. As a child on farms in northern Minnesota, I had worked with workhorse teams—mowing and raking hay, cleaning barns with crude sleds and manure forks—and in the summer we would sometimes ride these workhorses.

They were great, massive (weighing more than a ton), gentle animals and so huge that to get on their backs we either had to climb their legs—like shinnying up a living, hair-covered tree—or get them to stand near a board fence or the side of a hayrack (a wagon with tall wheels and a flatbed used for hauling hay from the field to the barn) so we could jump up and over onto their backs.

Once we were on their backs, with a frantic kicking of bare heels and amateur screaming of what we thought were correct-sounding obscenities—mimicked from our elders—and goading, they could sometimes be persuaded to plod slowly across the pasture while we sat and pretended to be Gene Autry or Roy Rogers—childhood cowboy heroes who never shot to kill but always neatly shot the guns from the bad guys’ hands and never kissed the damsels but rode off into the sunset at the end of the story. We would ride down villains who robbed stagecoaches or in other ways threatened damsels in distress, whom we could save and, of course, never kiss, but ride off at the end of our imagination.

The horses were—always—gentle and well behaved, and while they looked nothing like Champion or Trigger—Gene’s and Roy’s wonderful, pampered, combed, and shampooed lightning steeds (Champ was a bay, a golden brown, as I remember it, and Trigger was a palomino, with a blond, flowing mane and tail)—we were transformed into cowboys. With our crude, wood-carved six-guns and battered straw garden hats held on with pieces of twine, imagined with defined clarity that the pasture easily became the far Western range and every bush hid a marauding stage robber or a crafty rustler bent on stealing the poor rancher (my uncle, the farmer) blind.

Oh, it was not always so smooth. While they were wonderfully gentle and easy-minded, they had rules, and when those rules were broken, sometimes their retaliation was complete and devastating. On Saturday nights we went to the nearby town—a series of wood-framed small buildings, all without running water or electricity—wherein lived seventy or eighty people. There was a church there and a saloon, and in back of the saloon an added-on frame shack building with a tattered movie screen and a battery-operated small film projector. They showed the same Gene Autry film all the time, and in this film, Gene jumped out of the second story of a building onto the back of a waiting horse.

We, of course, had to try it, and I held the horse—or tried to—while my friend jumped from the hayloft opening in the barn onto the horse’s waiting back.

He bounced once—his groin virtually destroyed—made a sound like a broken water pump, slid down the horse’s leg, and was kicked in a flat trajectory straight to the rear through the slatted-board wall of the barn. He lived, though I still don’t quite know how; his flying body literally knocked the boards from the wall.

I personally went the way of the Native Americans and made a bow of dried willow, with arrows of river cane sharpened to needlepoints and fletched crudely with tied-on chicken feathers plucked from the much-offended egg layers in the coop, which I used to hunt “buffalo” off the back of Old Jim.

Just exactly where it went wrong we weren’t sure, but I’m fairly certain that nobody had ever shot an arrow from Old Jim’s back before. And I’m absolutely positive that no one had shot said arrow so that the feathers brushed his ears on the way past.

The “buffalo” was a hummock of black dirt directly in front of Jim, and while I couldn’t get him into a run, or even a trot, no matter what I tried, I’m sure he was moving at a relatively fast walk when I drew my mighty willow bow and sent the cane shaft at the pile of dirt.

Just for the record, and no matter what my relatives might say, I did not hit the horse in the back of his head.

Instead the arrow went directly between Jim’s ears, so low the chicken feathers brushed the top of his head as they whistled past.

The effect was immediate and catastrophic. Old Jim somehow gave a mighty one-ton shrug so that all his enormous strength seemed to be focused on squirting me straight into the air like a pumpkin seed, and I fell, somersaulting in a shower of cane arrows and the bow, with a shattering scream on my part and hysterical laughter on the part of the boy with me.

“You looked like a flying porcupine!” he yelled. “Stickers going everywhere . . . You was lucky you wasn’t umpaled.”

Which was largely true and seemed to establish the modus operandi for the rest of my horse-riding life. I do know that I couldn’t get close to Old Jim if I had anything that even remotely resembled a stick for the rest of that summer.

Horses are unique in many ways, though—and I know there will be wild disagreement here—not as smart as dogs, certainly when it comes to math.

I knew nothing of them then and perhaps little more now. But one of those summers I experimented with rodeo.

I was not good at it, to say the very least, and for me it was a particularly stupid thing to do because I was indeed so incredibly bad at it, and I did not do it for any length of time.

I tried bareback bronc riding for a few weeks. I learned some things: I learned intimately how the dirt in Montana tasted and learned that next to old combat veteran infantry sergeants, rodeo riders are the toughest (and kindest and most helpful) people on earth.

But I learned absolutely nothing about horses. I rarely made a good ride, a full ride, but even if I had, you cannot learn much in eight seconds on an animal’s back. . . .

And so to the Bighorn Mountains.

• • •

It is probably true that all mountains are beautiful; there is something about them, the quality of bigness, of an ethereal joy to their size and scenic quality. And I have seen mountain ranges in Canada, the United States, particularly Alaska, have run sled dogs in them and through them and over them and have been immersed in their beauty as with the old Navajo prayer:

Beauty behind me

Beauty before me

Beauty to my left

Beauty to my right

All around me is beauty.

But there is something special about the Bighorns in Wyoming.

I found a small house at the base of a dirt track called the Penrose Trail, which led directly up out of the town of Story into the lower peaks and a huge hay meadow called Penrose Park.

If memory serves, it is twenty or so miles from Story up to the meadow, then a few more miles to an old cabin on a lake and the beginning of a wilderness trail through staggering beauty; the trail is called the Solitude Trail—among other nicknames—and it wanders through some seventy miles of mountains in a large loop.

Older people who lived in Story, who rode the mountains before there were trails, told me of the beauty in the high country, and it became at first a lure, a pull, and then almost a drive.

I wanted to see the country, the high country, as I had seen it in Alaska with dog teams; the problem here was that it was summer, too hot for dogs, the distances were much too great, and my dislike of hiking much too sincere for me to even consider backpacking through the mountains.

And so, to horse.

Unfortunately, I knew little or nothing as to how one goes about acquiring a horse to ride on potentially dangerous mountain trails.

And then another horse to pack gear on those same possibly dangerous mountain trails.

For those who have read of my trials and tribulations when I tried to learn how to run dogs for the Iditarod, you will note a great many similarities in the learning procedure, or more accurately, how the learning processes for both endeavors strongly resembled a train wreck. It is true that I have for most of my life lived beneath the military concept that “there is absolutely no substitute for personal inspection at zero altitude” when it comes to trying to learn something. While functional, the problem with this theory is that it often places you personally and physically at the very nexus of destruction. Hence both legs broken, both arms broken more than once, wrists broken, teeth knocked out, ribs cracked and broken, both thumbs broken more than once (strangely more painful than the other breaks) and—seemingly impossible—an arrow self-driven through my left thumb.

Among other bits of lesser mayhem . . .

I had read many Westerns, of course, doing research, and had even written several, had indeed won the Spur Award from the Western Writers of America three times for Western novels. This is perhaps indicative of excess glibness, considering how little I apparently knew. But I had read all those books and seen God knows how many Western films and knew that people had used packhorses. I had run two Iditarod sled-dog races across Alaska, and I thought—really, it seemed to be that simple—that if a person could do one, he could do the other.

The problem was that I did not know anyone involved with horses and so—as God is my witness—I went to the yellow pages for Sheridan, Wyoming (the nearest town of any size), looked under “horse,” and near the end of the section, found a listing of horse brokers. (This was before there was a viable Internet to use.)

Perfect, I thought. There were people who bought and sold horses—exactly what I needed. The first two names I called were not available, but on the third call, a gruff voice answered with a word that sounded like “haaawdy” and then asked, “Whut due ya’ll need . . . ?”

“It’s simple, really,” I answered. “I need two horses. One to ride, one to carry a pack. I want to go up into the Bighorn Mountains. . . .”

“Why, sure you do.” There was a pause, a long pause. I would surmise later, when I knew more of horse brokers, that he either thought I was joking, or, if he were very lucky, that I was uncompromisingly green, bordering on being perhaps medically stupid, and he had a chance to make his profit for the year on a one- or two-horse deal.

It was, of course, closer to the latter.

“Where do you live?” he asked.

“Story.” I named the small town at the base of the Bighorns, near where the Penrose Trail comes out, or down and out. I had purchased a small house there with a few acres of thick grass, and I was surprised to find it vacant. I was to find later—and there were so many “laters” when dealing with Wyoming—near the end of October, why this was to be, when the first late-October snow, a crushing thirty-two inches, came in one day, followed two days later by another thirty inches.

But back then I was wonderfully innocent; it was a grand summer day and the mountains beckoned, pulled, demanded that I come to them as I had in winter in Alaska with dogs during the Iditarod. “Where should I come?” I asked.

“No,” he said quickly. “I’ll come to you with the horses. I have two that are perfect for you.”

“Well, let me . . .” I was going to say, “Let me get ready for them,” as I had no idea what one did, really, to have and keep horses. The property had a small pasture with two feet of grass and a three-sided shed, was surrounded by tall ponderosa pines for shade and little else.

But he hung up before I could get another word out, and it seemed that I had just turned around when a large, gaudy pickup hooked to a flashy two-horse trailer pulled into the driveway. It’s difficult to describe it without lapsing into poor taste; indeed, the truck and trailer alone were a monument to the word “god-awful.” The color was an eye-ripping red with black rubber mudguards, and on each mudguard was a chrome silhouette of a nude woman, and across the front of the hood was—I swear—an actual six-foot-wide longhorn mounted in a silver boss with an engraving (again, I couldn’t make this up) of another nude woman with impossibly large features, which was, in turn, matched by the mudguards on the trailer and a large painted silhouette of a nude on the front of the trailer cleverly positioned so that a small ventilation opening for the horses to put their heads out . . . Well, you get the picture.

And if the truck and trailer were in bad taste, they were nothing compared to the man. Tall but with a large beer belly covered by an enormous silver and gold belt buckle with RODEO engraved over yet another silhouette of a nude woman, on top of tailor-cut jeans tucked inside knee-high white cowboys boots with (a major change in art forms) a bright blue bald eagle stitched on the front.

On his head was an impossibly large cowboy hat with a silver hatband, which I at first thought was made of little conchos but turned out to be little silhouettes of, right . . . more women.

He shook my hand without speaking, turned and opened the back of the trailer, and let two horses step out at the same time, which meant they weren’t tied in, nor did they have butt chains on—two major mistakes that prove he knew little about trailering horses and hence little about horses themselves.

Not that it mattered. I had already made up my mind that looking in the yellow pages cold for a horse broker was Very Wrong and that I wouldn’t buy a horse from this guy if he gave them away.

And yet . . .

And yet . . .

A thing happened, something I had never seen before.

The horses were simply standing there, at relative peace—no nervousness at all—and there was something about them that seemed, well, inviting. And I thought, felt, that I should go to them and touch them, pet them. I know how that sounds, and I have never been all “woo-woo” about animals, especially horses, of which I knew little except that they were big, huge, nine hundred to a thousand pounds, and potentially dangerous. Very dangerous. Decidedly so if they were startled or panicked or surprised. At that time I had had two friends killed while riding them and knew of several others permanently in wheelchairs. (This was years before actor Christopher Reeve, who as an excellent, Olympic-level rider, was permanently completely disabled—which led directly to his later death—when falling on a simple training jump.)

I actually took a step toward them—worse, toward their rear ends, which is never the way you walk up on a strange horse—before stopping.

Josh, my border collie, my friend, had been at my side watching, and before I could move farther, he rose from a sitting position, trotted forward, and without hesitating at all, trotted between the back legs of the mare, paused beneath her belly, then continued up through the front legs. At that moment she lowered her head and they touched noses, whereupon Josh turned to the right, touched noses with the black horse, who had lowered his head, trotted between his front legs, paused under the belly, through his back legs, then back in front of me, where he sat, looked up and—I swear—nodded.

Or it seemed that he nodded.

Or he wanted to nod.

Or he wanted me to think that he nodded.

Or he wanted me to know something. Something good about the horses.

What we had witnessed—the broker and I—had been nothing less than a kind of miracle. Dogs, perhaps many dogs, had been killed simply by getting too close to the back feet of a horse. Years later I would acquire a horse who had mistakenly killed his owner, a young woman who was checking his back feet, when a dog came too close. As it kicked at the dog, the horse caught the woman in the chest with a glancing blow. The force was so powerful it severed her aorta and she bled to death before help could arrive.

For Josh to so nonchalantly trot through the mare’s legs, as well as the legs of the black cow pony, then back to me, came in the form of a message. . . .

And I listened.

I had by that time lived with dogs, run with dogs, camped with dogs, for literally thousands and thousands of joyous and not a little educational miles. I had been saved, my life saved, many times by dogs—mainly lead dogs—making decisions about bad ice or moose attacks in the night, and I had learned again and again of my own frailty, slowness of thought and action compared to what the dogs could accomplish. And while at first I had trouble believing, because I was as chauvinistic as most humans are, at last I surrendered my own will and abilities to that of the dogs, and when Josh gave his okay to the horses, I listened and bought the horses no matter my feelings for the broker. And the four of us—horses, dog, and I—spent a wonderful summer exploring the wilderness areas of the Bighorn Mountains in Wyoming.

And through all of it—swimming rivers, climbing impossible ridges and grades, running into bear, moose, and one unforgettable brush with a mountain lion—the horses never once let me down or even gave me a moment’s pause. Indeed, as the summer passed, I came to rely more on them—and their relationship with Josh—than on my own judgment. And the knowledge came that the three of them were actually running things and I was just along for the wonderful ride. Again and again as we went into the mountains I relinquished my feeling of individual, my feeling of self, to the three of them; we would start up the mountain out of the yard, and within a few hundred feet the mare—which I habitually rode, using the little black pony for packing—would take over and run the show. Josh would go out ahead on the trail, and if he ran into anything—a moose or an elk or, less frequently, a bear—he would come back and look at the mare, and she would slow and let me come to attention and react. When the ride got long, as it sometimes did, and Josh grew tired (he ran at least six miles for every mile the horse covered) and there was a long flat area, such as a meadow, he would wait until there was a boulder or nearby hummock and would jump up behind me on the mare and ride for a while, sitting on her rump. When—how—they worked this out, I had no idea. I had never seen it before and never since, with other dogs and horses. But they did it, irrespective of me, and as we rode, the seeds for this book were planted. And as they sprouted and grew with note taking and the mining of my childhood memories came the belief, the solid belief, that it is true not just for me but for all of us.

We don’t own animals. Even those we kill to eat.

We live with them.

We get to live with them.

And so to Corky.

• • •

To shorten what many people have come to think of as a kind of madness—indeed, an earlier book of mine terms it a kind of madness—I decided at the age of sixty-seven to go back to dogs and Alaska and run the Iditarod again.

There are/were many reasons for this decision to run it after a lapse of twenty years, but for people with normal lives they do not seem even remotely logical. In many respects I think it is something on the order of combat; for people who have never experienced it, it is impossible to explain except to say it is outrageous, and for people who have done it, no explanation is necessary.

I missed the dogs.

Terribly.

Every day I thought of them: dogs long gone, old friends passed, and the joy and beauty they gave me.

And I missed the wilds of Alaska, to run through and in them with a dog team, alone and silent in such staggering beauty. When I took a friend of mine from Scotland to Alaskan mountains and rivers and forest—this was an articulate, well-read, educated friend—he could only stand, half crying, and say, “Jesus Christ,” over and over again in a kind of prayer.

All of that. The wild and the dogs and the stunning joy of dancing through the wilderness with them hung over me—no, danced out ahead of me—every single waking minute of every single waking day.

The hard thing to understand is that I ever left it, that I didn’t go back to the dogs sooner. Age didn’t seem to matter; nor did physical condition, though everything crazy you do when you’re young, every bar fight, every rough horse ridden and thrown from, every torturous twist the military does to your body comes back with a kind of staggering vengeance when you get old. Creaking bones, small and large traveling pains, bad vision . . .

And none of it seemed to matter even remotely; the pain became a kind of wonderful recognition that I was still alive, another obstacle to beat or, as the Marines put it, “Pain is weakness leaving the body.” Bushwa, of course, but it was and is that way for me and so I found some sled dogs.

And then more sled dogs.

And still more sled dogs.

And equipment . . .

I bought an old Ford truck with a dog box on it, found a shack in the woods in northern Minnesota, and tried training there. When that didn’t work—way too crowded; I waited at a trail intersection one afternoon while one hundred and four snow machines (at least fifty of them were pulling work sleds loaded with cases of beer) passed in front of my lead dog—I cut, as they say, and ran to Alaska, where I found an ugly old house, a kind of huge suburban shack, back in the bush, and sort of moved in.

“Sort of,” because there were no facilities for sled dogs. Each dog needed a post driven into the ground, with a chain and an insulated house. I could have kept them on a picket chain while I built the kennel—which would take two months; I would have to rent a bulldozer to clear a place, drill holes, build houses, etc. That seemed excessive, to have them confined to short pickets for all that time.

Luckily, a company would take the dogs to Juneau, put them up on the snow/glaciers for the summer to give rides to tourists, feed them whatever food I wanted to feed them, and in general take really good care of them. Plus they would continue to get healthy exercise.

I agreed to it, drove them to Juneau, watched them take helicopter rides up to the glacier—a singular experience for dogs who have never been off the ground—and came back to a house empty of dogs. It was a strange feeling—as if my family were suddenly gone.

I rented a bulldozer and cleared four acres of the small—if ancient—black spruce and set to work. In Wasilla there was a place where good tools could be rented, and I found a kind of machine for drilling four-foot-deep-by-eight-inch-wide holes in the ground. It was not the small auger type, but a large rig on wheels that made an extraordinary amount of noise and slamming motions while it was running so that it required constant attention and it was impossible to see or hear anything else.

And now a brief note on Alaska. Many people say many mistaken things about the state, people who have never lived there, as if it were a kind of Disneyland of the north, with quaintly “cute” animals like wolves, bears, and moose, which seem to have been placed there somehow for photo opportunities. Those are largely people who never truly get off the bus but shoot pictures through the windows.

The truth is Alaska is for real, and with a lack of knowledge, of understanding, this reality comes with sometimes great and sometimes lethal danger. At the time of this writing, a young woman schoolteacher visiting one of the outlying villages went for a jog—which she was accustomed to doing in the Lower 48—and was dragged down, killed, and eaten by wolves. Bears attack frequently—both black bears and grizzlies—as do moose, which can do great damage by kicking. (They are as strong as horses.) I personally know of several people severely injured by moose and four killed and eaten by bears.

When I moved back up to Alaska, I had in a strange way fallen into the category of the ignorant tourist. I had run two Iditarods, it was true, back in l983 and l985, but then I had been just visiting in winter when bears were in hibernation and did not understand or truly know the possibilities of summer attacks by bears.

And I bought a house at the end of a road that terminated on the very edge of a wilderness that stretched for literally thousands of miles. Not a road or village or settlement or power line or even a single person existed in this staggering immensity. Just wild things in the wild.

And I took a bulldozer and cleared four acres and moved in more or less like I owned the place.

Well.

Many things disagreed with me about this so-called ownership. On the first warm day, approximately two hundred million mosquitoes decided to express this disagreement and came to call. Then bears hit my trash, and I think it was a wolverine (there are no skunks in Alaska proper—nor snakes) that sprayed on most of what I had outside. A moose dented the top of my truck hood—I think just to be annoying. It was strange because I was alone—my dog handler being with the dogs on the glacier in Juneau—and I kept feeling as though I was being watched.

And I was.

About halfway through the afternoon of the second day with the heavy boring machine slamming me around, I felt a call from nature and I shut the machine down and went into the house to answer that call. I wasn’t gone fifteen or twenty minutes, but when I came out, I found I was not alone.

The drilling rig had kicked up a pile of soft dirt next to the hole, and there, in that pile of soft dirt, was a single bear track that measured seven and a half inches wide by eleven and a half inches long.

Grizzly.

Easily twice the size of most black bears.

It had been watching me.

Every hair on the back of my neck stood up.

It had stood there, back in the thick trees—not thirty or forty feet away—and watched me drilling holes. As soon as I’d gone into the house, it had come forward to see what I had been doing—to check out the hole—and I hadn’t seen or heard a thing.

I’d had no clue.

The next time, I thought, it could come up behind me while I was running the machine and simply bite my head off. (One of the bear attacks I had heard of ended in just that way—one bite, clean off. Like a guillotine.)

Strangely, it was not the fear of an attack that bothered me as much as the fact that I was alone, some kind of strange dread of that dark band of spruce and that bears, or any other animal, could stand there and watch and I wouldn’t know it.

I needed company. Somebody to watch my back. Somebody to give me at least a small warning.

I needed, really, a dog. And all my sled dogs were gone, up on the glacier for the summer.

And a gun.

I needed a dog for company and a gun—which I did not have—for possible protection. It being so complicated to drive across Canada with firearms, I had left my weapons with my son in Minnesota.

A gun was not a problem. Wasilla had several pawnshops. At one, I purchased a used Mossberg twelve-gauge pump, which held five rounds and had a slightly shortened barrel. I also bought a box of Magnum full-diameter slugs and another box with Magnum double-ought buckshot, fifteen thirty-caliber-round balls per shell, each ball a third of an inch in diameter. Either way, slugs or buckshot, pumping in one after the other, I could pretty much stop a charging Buick.

False security, as we will find later.

As for the dog, I always got my pets at animal shelters, so I called the Wasilla shelter and was told—perfect, really—that they had a three-legged border collie that needed a good home. He would make a great pet and work companion. I had, over the years, saved several border collies and found them to be something just a little better than wonderful—way smarter than me—and I planned for him to stay a house pet after the team came back from the glacier in Juneau.

The rule was first come, first served, and there had been another call on the border collie. So I jumped in my truck and roared the forty miles to Wasilla, then on down near the town of Palmer, slid into the parking lot at the shelter . . .

Just, as it turned out, seven minutes too late.

The other people had come for the border collie. Which was fine—they would give it a good home. I asked the woman at the shelter if she had another dog that might be suitable.

“Well . . . there is one that we just got and can’t afford to keep, since it will need a lot of medical and dental care and we don’t have any money. . . .”

Oh, I thought. Good. Medical bills. “Well, I don’t know. I kind of need one pretty quick. . . .”

“He was scheduled to be put down tomorrow if nobody showed for him.”

Well. She was probably playing me, but that was all right; you do what you have to do to save a dog, and she was hitting the target perfectly. I could not stand to have a dog put down. In a moment of illogical compassion and perhaps some weakness, I said: “All right. Bring him out.”

And so I met Corky. An eight-pound toy poodle covered with abscesses, mouth filled with rotten teeth, one ear and his butt packed with pus. He was probably ten or eleven years old, though the people who dumped him said in a form that he was only six. They also said that the reason they were leaving him was that he was “too rambunctious.”

“What did he do?” I asked as they brought him out in the little kennel the people had left him in. “Rip the tires off the car?” How the hell could such a little thing be “too rambunctious”?

There was no way, I thought, that this dog would be able to save me from grizzlies. . . . He’d be lucky to get home alive, judging by the way he looked.

And yet.

And yet there he was, looking at me through sickened, red eyes, wanting something, wanting me to sign, to acknowledge the contract, the age-old contract between a man and a dog, the contract that says simply, “I will be for you if you will be for me. . . .”