Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

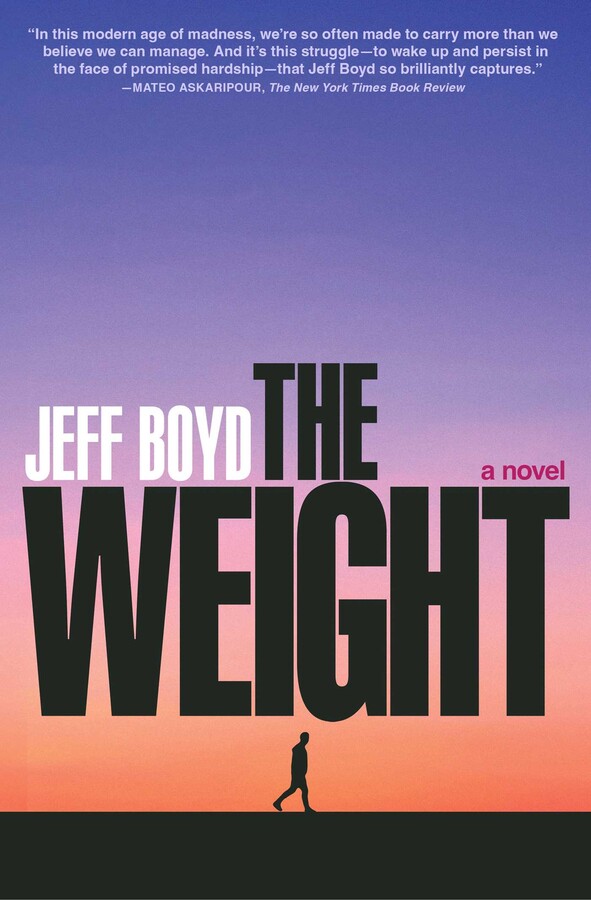

About The Book

A powerful coming-of-age novel about a twenty-something Black musician living in predominantly white Portland, Oregon, playing in a rock band on the verge of success while struggling with racism, romance, and the legacy of his strict religious upbringing.

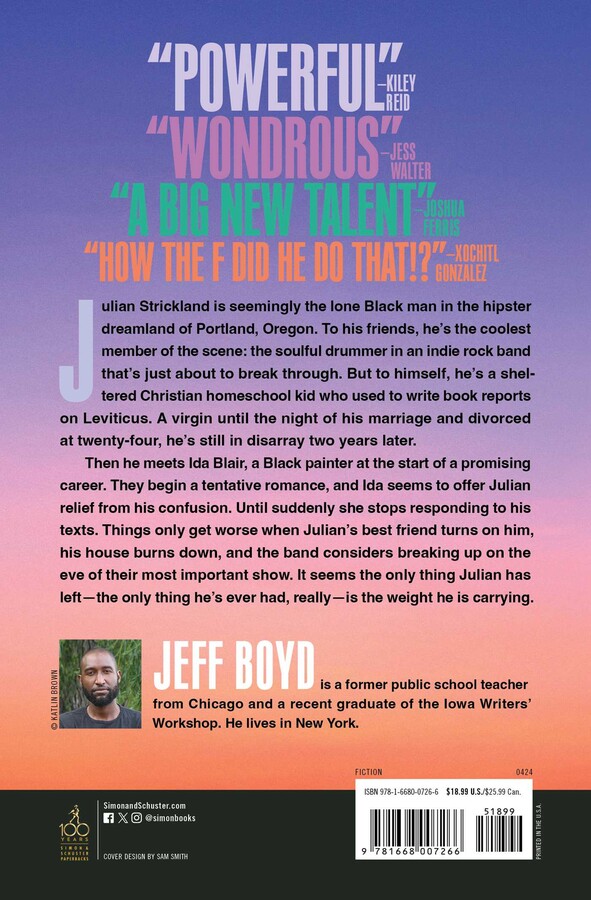

Julian Strickland is seemingly the lone Black man in the hipster dreamland of Portland, Oregon. To his friends, he’s the coolest member of the scene: the soulful drummer from Chicago in an indie rock band that’s just about to break through. But to himself, he’s a sheltered Christian homeschool kid who used to write book reports on Leviticus. A virgin until the night of his marriage, divorced at twenty-four, he’s still in disarray two years later—pretending to fit in, wondering if any of his relationships are real, estranged from his family, and struggling to reconcile his relationship with God.

Then he meets Ida Blair, a Black painter at the start of a promising career. They begin a tentative relationship, and Ida seems to offer Julian relief from his confusion. But suddenly she stops responding to his texts. Things only get worse when Julian’s best friend mysteriously turns on him, his house burns down, and the band considers breaking up on the eve of their most important show yet. It seems the only thing Julian has left—the only thing he’s ever had, really—is the weight he is carrying.

Jeff Boyd’s beguiling first novel is a piercing exploration of faith, racial identity, love, and friendship—woven of acid humor, disarming vulnerability, and unforgettable poignance.

Julian Strickland is seemingly the lone Black man in the hipster dreamland of Portland, Oregon. To his friends, he’s the coolest member of the scene: the soulful drummer from Chicago in an indie rock band that’s just about to break through. But to himself, he’s a sheltered Christian homeschool kid who used to write book reports on Leviticus. A virgin until the night of his marriage, divorced at twenty-four, he’s still in disarray two years later—pretending to fit in, wondering if any of his relationships are real, estranged from his family, and struggling to reconcile his relationship with God.

Then he meets Ida Blair, a Black painter at the start of a promising career. They begin a tentative relationship, and Ida seems to offer Julian relief from his confusion. But suddenly she stops responding to his texts. Things only get worse when Julian’s best friend mysteriously turns on him, his house burns down, and the band considers breaking up on the eve of their most important show yet. It seems the only thing Julian has left—the only thing he’s ever had, really—is the weight he is carrying.

Jeff Boyd’s beguiling first novel is a piercing exploration of faith, racial identity, love, and friendship—woven of acid humor, disarming vulnerability, and unforgettable poignance.

Excerpt

Chapter 1 1

THE PLACE WAS A RUIN. Painted blue so many years ago, its primary color was now dirt brown. William walked up to the house’s front landing. I stayed on the sidewalk. It was a beautiful day, but if anyone was inside the house, they didn’t seem to care. There was a window to the right of the door and the blinds were drawn. The doorbell didn’t work. The screen door was locked. William hit it a couple times. The frame rattled violently, and still no one came to the door.

“Can’t you just call the guy?” I asked him.

He turned to me and shook his head no. “I don’t have his number,” he said.

Two houses down, a white woman was standing by a street-side mailbox. She was watching us.

“Let’s get out of here,” I said.

“Hold on a minute. Maybe we should ask those guys across the street.”

On the front porch of the house across the street there were two sketchy white dudes sitting on lawn chairs smoking cigarettes. When we first pulled up, William had waved to them, and they’d acted like we didn’t exist, eyes not focused on anything in this world. I took a quick glance behind me. Nothing about them had changed. I turned back to William.

“No way,” I said.

“Then we should head around back and see if it’s still there.”

“I’m not trying to get shot over a damn fire pit,” I said.

William smiled.

“Good buddy,” he said. “Don’t be silly. No one’s going to shoot us.”

He acted like I was being absurd. Well, I’d never heard of a white guy like him getting shot in a stranger’s backyard for no good reason. For people like me, that kind of shit happened all the time. Despite that fact, I followed him anyway, refusing to let him believe that he was brave and I was a coward.

We walked across the empty driveway to the left side of the house where a string slipped through a hole in a wooden fence. William pulled the string and yanked the handle. The gate didn’t budge. He threw up his hands in defeat. He was the kind of guy who got surprised when a door didn’t open for him almost automatically. He was lucky to have me with him. Standing on my toes, I reached over the fence and pulled up the latch.

We entered the backyard. The blinds on the back of the house were closed just like the front. The sliding glass windows were covered with paper bags so you couldn’t see inside. The wooden deck was rotten, big holes, missing panels. No signs of life. No outside furniture. Only the fire pit standing alone amid high grass and weeds, like bait to a trap.

William walked up to the fire pit without concern, but I approached cautiously. When I stepped on a twig and it snapped, my body braced for an explosion. Seconds slowly passed and, somehow, I was still alive.

The risks I took for my friends. I was a friendship soldier sometimes. I kept marching ahead until I stood next to William.

The fire pit was about three feet in diameter, a big black metal bowl with slanted legs. The bottom of the iron cylinder contained ash, burnt wood, and a carton’s worth of cigarette butts.

“Let’s dump this shit out and bounce,” I said.

“That’s not how I roll,” William said.

I thought he might take it as an admission of my fear if I followed him to his car just for him to grab a trash bag, so I stayed in the backyard, trespassing by myself. I looked over the low wooden fence to the neighbor’s backyard. An out-of-commission refrigerator was toppled over in the grass. Two rusted cars without wheels sat on cinder blocks underneath a giant tree. I didn’t see a soul, and somehow that only made me feel worse, like I could be shot at any moment without knowing it was coming. Every second alone felt like an eternity. I wished I still believed in the power of prayer.

William came back with a paper sack and held it open. I tilted the fire pit. A lot of shit missed the bag. He bent down to grab a chunk of burnt wood and it turned into ash and fell through his fingers. Undeterred, he kept picking up little pieces. He picked up a couple of cigarette butts and tossed them into the bag.

“This is going to take forever,” I said.

He looked up at me from his crouched position.

“Then how about you help instead of just standing there?”

“Fine,” I said. “Get out of my way.”

He stood up and moved aside. I stomped at the debris until everything disappeared into the grass. William sighed as if he didn’t like my method of cleaning, but he didn’t tell me to stop. We picked up the fire pit and headed out front. It was heavy and I was walking backwards. I tried to move faster.

“What’s wrong with you today?” William asked.

“My fingers are getting numb,” I said.

“You want to take a break?”

“No,” I said. “I want you to hurry up.”

The woman who’d been watching us from a mailbox now stood behind William’s Subaru, blocking our access to the trunk. She wore a white sweatshirt with a large screen print of Minnie Mouse driving a red convertible down a scenic cartoon highway. Her wispy white hair was the sons of Noah after the flood—wild in every direction. She had a flip phone flipped open with her thumb over the call button like any false move and boom! she’d call the cops.

We set the fire pit down in front of her.

“You boys moving in?” she asked.

“We’re just here for the pit,” I said.

“How’d you know it was back there?”

“It was listed for free on Craigslist,” William said.

“That’s peculiar,” she said. “Last tenants moved out about a month ago. And good riddance to those godforsaken meth heads.” She put her phone in her pocket but didn’t move away. Instead of moving, she told us the last tenants used to pack the garage with stolen bikes and spray-paint them with the door opened only a smidge. “The fumes almost killed me from all the way across the street. I don’t know how they survived. Must have been all the drugs. They were invincible, like cockroaches. Unwanted just the same.”

She spoke so loudly I got the impression she was also addressing the dudes across the street. Letting them know she had an eye on them as well. She went on and on about the transgressions of the last tenants. William kept nodding like he understood this lady’s troubles, like he hadn’t grown up a San Diego surfer kid with adolescent memories of being stoned and playing guitar on the beach with his friends as the sun disappeared into the ocean. Fine for him. But what if the zombies across the street woke up and decided to cause trouble for the Black man? I wanted to tell her to get the hell out of our way. Yet I didn’t want to do anything to make her call the cops.

Once she finally moved, we put the fire pit in the trunk and headed for home. From the safety of the car, I waved to the zombies as we drove away. They waved back. Maybe they weren’t so murderous after all, but how was I to know until it was too late?

Finally out of Gresham, back in Portland, William rolled the windows down. He was enjoying the drive. He took the tree-lined route home instead of the fast one.

“Thanks for helping me out,” he said.

“My pleasure,” I said.

And even with the danger, I was being sincere. I was happy to help him because I missed him. We used to be the kind of roommates who did everything together. We used to sit in our living room and get stoned and listen to music and drink and talk until the sun came up. A few times we’d pissed in the toilet at the same time so there’d be no interruption in the conversation we were having. But not anymore, not since things got serious with him and Skyler. Now, except for band stuff, we barely saw each other. Which is why I’d agreed to help him with the fire pit in the first place, so we could spend some time together just the two of us. But our errand had taken longer than I’d thought it would. It was close to three o’clock and I had somewhere else to be.

“Mind speeding up a little?”

“What’s the hurry?”

“I’m supposed to meet up with Anne.”

“Why?”

“Why not?”

“Because she’s engaged.”

“Exactly,” I said. “That’s why we need to talk.”

“But what’s there to talk about?”

“Just speed the hell up, man.”

“Jesus,” he said. “Fine. It’s your funeral.”

He rolled up the windows and pressed on the gas. I sat in the passenger seat and hoped I wasn’t headed for the end.

THE PLACE WAS A RUIN. Painted blue so many years ago, its primary color was now dirt brown. William walked up to the house’s front landing. I stayed on the sidewalk. It was a beautiful day, but if anyone was inside the house, they didn’t seem to care. There was a window to the right of the door and the blinds were drawn. The doorbell didn’t work. The screen door was locked. William hit it a couple times. The frame rattled violently, and still no one came to the door.

“Can’t you just call the guy?” I asked him.

He turned to me and shook his head no. “I don’t have his number,” he said.

Two houses down, a white woman was standing by a street-side mailbox. She was watching us.

“Let’s get out of here,” I said.

“Hold on a minute. Maybe we should ask those guys across the street.”

On the front porch of the house across the street there were two sketchy white dudes sitting on lawn chairs smoking cigarettes. When we first pulled up, William had waved to them, and they’d acted like we didn’t exist, eyes not focused on anything in this world. I took a quick glance behind me. Nothing about them had changed. I turned back to William.

“No way,” I said.

“Then we should head around back and see if it’s still there.”

“I’m not trying to get shot over a damn fire pit,” I said.

William smiled.

“Good buddy,” he said. “Don’t be silly. No one’s going to shoot us.”

He acted like I was being absurd. Well, I’d never heard of a white guy like him getting shot in a stranger’s backyard for no good reason. For people like me, that kind of shit happened all the time. Despite that fact, I followed him anyway, refusing to let him believe that he was brave and I was a coward.

We walked across the empty driveway to the left side of the house where a string slipped through a hole in a wooden fence. William pulled the string and yanked the handle. The gate didn’t budge. He threw up his hands in defeat. He was the kind of guy who got surprised when a door didn’t open for him almost automatically. He was lucky to have me with him. Standing on my toes, I reached over the fence and pulled up the latch.

We entered the backyard. The blinds on the back of the house were closed just like the front. The sliding glass windows were covered with paper bags so you couldn’t see inside. The wooden deck was rotten, big holes, missing panels. No signs of life. No outside furniture. Only the fire pit standing alone amid high grass and weeds, like bait to a trap.

William walked up to the fire pit without concern, but I approached cautiously. When I stepped on a twig and it snapped, my body braced for an explosion. Seconds slowly passed and, somehow, I was still alive.

The risks I took for my friends. I was a friendship soldier sometimes. I kept marching ahead until I stood next to William.

The fire pit was about three feet in diameter, a big black metal bowl with slanted legs. The bottom of the iron cylinder contained ash, burnt wood, and a carton’s worth of cigarette butts.

“Let’s dump this shit out and bounce,” I said.

“That’s not how I roll,” William said.

I thought he might take it as an admission of my fear if I followed him to his car just for him to grab a trash bag, so I stayed in the backyard, trespassing by myself. I looked over the low wooden fence to the neighbor’s backyard. An out-of-commission refrigerator was toppled over in the grass. Two rusted cars without wheels sat on cinder blocks underneath a giant tree. I didn’t see a soul, and somehow that only made me feel worse, like I could be shot at any moment without knowing it was coming. Every second alone felt like an eternity. I wished I still believed in the power of prayer.

William came back with a paper sack and held it open. I tilted the fire pit. A lot of shit missed the bag. He bent down to grab a chunk of burnt wood and it turned into ash and fell through his fingers. Undeterred, he kept picking up little pieces. He picked up a couple of cigarette butts and tossed them into the bag.

“This is going to take forever,” I said.

He looked up at me from his crouched position.

“Then how about you help instead of just standing there?”

“Fine,” I said. “Get out of my way.”

He stood up and moved aside. I stomped at the debris until everything disappeared into the grass. William sighed as if he didn’t like my method of cleaning, but he didn’t tell me to stop. We picked up the fire pit and headed out front. It was heavy and I was walking backwards. I tried to move faster.

“What’s wrong with you today?” William asked.

“My fingers are getting numb,” I said.

“You want to take a break?”

“No,” I said. “I want you to hurry up.”

The woman who’d been watching us from a mailbox now stood behind William’s Subaru, blocking our access to the trunk. She wore a white sweatshirt with a large screen print of Minnie Mouse driving a red convertible down a scenic cartoon highway. Her wispy white hair was the sons of Noah after the flood—wild in every direction. She had a flip phone flipped open with her thumb over the call button like any false move and boom! she’d call the cops.

We set the fire pit down in front of her.

“You boys moving in?” she asked.

“We’re just here for the pit,” I said.

“How’d you know it was back there?”

“It was listed for free on Craigslist,” William said.

“That’s peculiar,” she said. “Last tenants moved out about a month ago. And good riddance to those godforsaken meth heads.” She put her phone in her pocket but didn’t move away. Instead of moving, she told us the last tenants used to pack the garage with stolen bikes and spray-paint them with the door opened only a smidge. “The fumes almost killed me from all the way across the street. I don’t know how they survived. Must have been all the drugs. They were invincible, like cockroaches. Unwanted just the same.”

She spoke so loudly I got the impression she was also addressing the dudes across the street. Letting them know she had an eye on them as well. She went on and on about the transgressions of the last tenants. William kept nodding like he understood this lady’s troubles, like he hadn’t grown up a San Diego surfer kid with adolescent memories of being stoned and playing guitar on the beach with his friends as the sun disappeared into the ocean. Fine for him. But what if the zombies across the street woke up and decided to cause trouble for the Black man? I wanted to tell her to get the hell out of our way. Yet I didn’t want to do anything to make her call the cops.

Once she finally moved, we put the fire pit in the trunk and headed for home. From the safety of the car, I waved to the zombies as we drove away. They waved back. Maybe they weren’t so murderous after all, but how was I to know until it was too late?

Finally out of Gresham, back in Portland, William rolled the windows down. He was enjoying the drive. He took the tree-lined route home instead of the fast one.

“Thanks for helping me out,” he said.

“My pleasure,” I said.

And even with the danger, I was being sincere. I was happy to help him because I missed him. We used to be the kind of roommates who did everything together. We used to sit in our living room and get stoned and listen to music and drink and talk until the sun came up. A few times we’d pissed in the toilet at the same time so there’d be no interruption in the conversation we were having. But not anymore, not since things got serious with him and Skyler. Now, except for band stuff, we barely saw each other. Which is why I’d agreed to help him with the fire pit in the first place, so we could spend some time together just the two of us. But our errand had taken longer than I’d thought it would. It was close to three o’clock and I had somewhere else to be.

“Mind speeding up a little?”

“What’s the hurry?”

“I’m supposed to meet up with Anne.”

“Why?”

“Why not?”

“Because she’s engaged.”

“Exactly,” I said. “That’s why we need to talk.”

“But what’s there to talk about?”

“Just speed the hell up, man.”

“Jesus,” he said. “Fine. It’s your funeral.”

He rolled up the windows and pressed on the gas. I sat in the passenger seat and hoped I wasn’t headed for the end.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (May 15, 2024)

- Length: 336 pages

- ISBN13: 9781668007266

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Weight Trade Paperback 9781668007266

- Author Photo (jpg): Jeff Boyd Katlin Brown(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit