Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

• Presents Crowley’s preferred text, drawing on all existing draft manuscripts and margin notes from Crowley’s personal copies

• Contains an introduction and explanatory notes by Crowley biographer Richard Kaczynski, helping to illuminate obscure passages and references

• Includes Crowley’s mystical essays on his first forays into sex magic, his initial embrace of the legendary title of “the Beast,” and his encounters with the Golden Dawn, Buddhism, Agnosticism, and Christianity

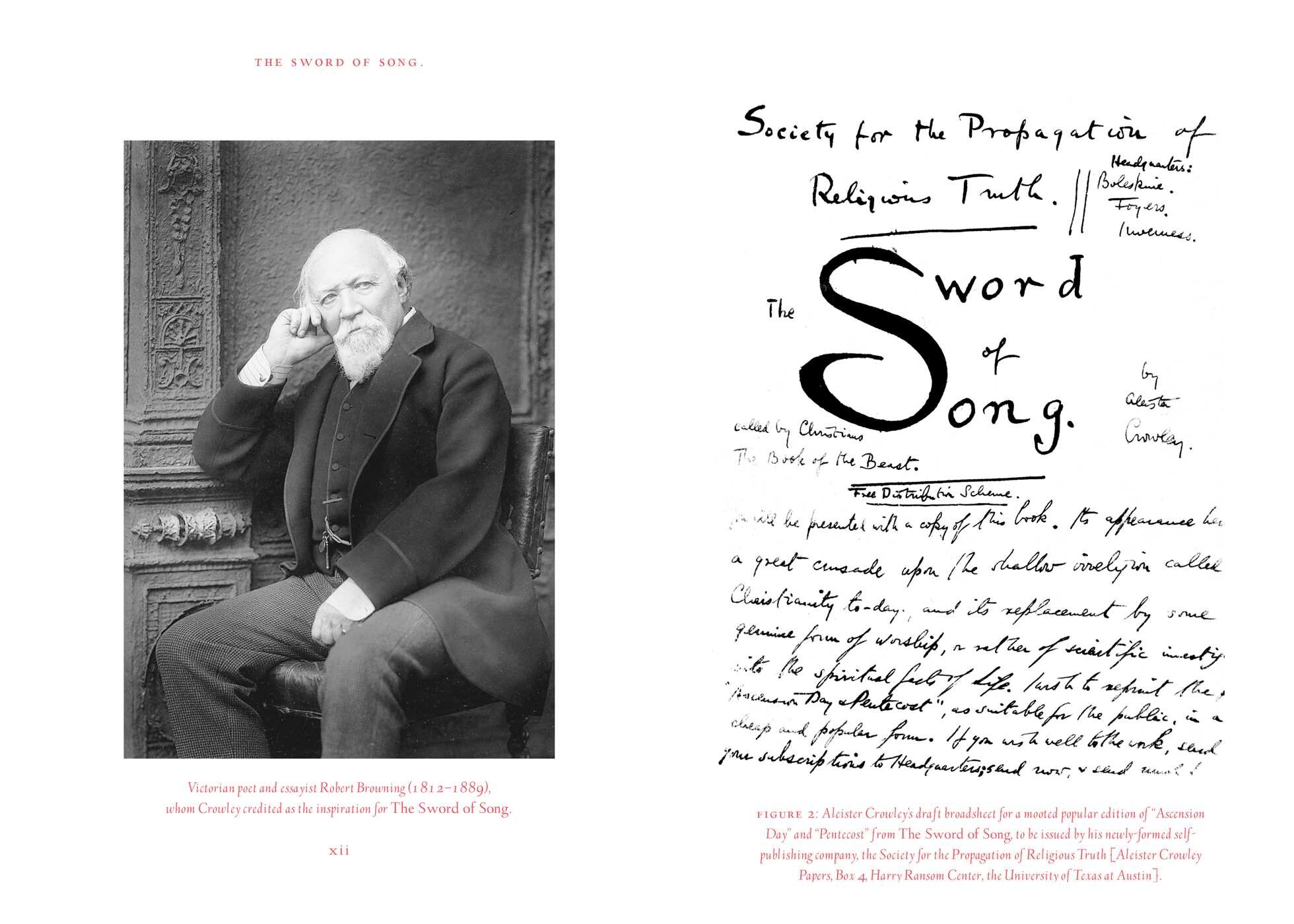

Too inflammatory for English publishers, Aleister Crowley printed The Sword of Song, his first talismanic work, in Paris in 1904, releasing a mere one hundred copies. Deconstructing his encounters with the Golden Dawn, Buddhism, Agnosticism, and Christianity, the book explored Crowley’s magic and spiritual philosophy before he experienced the revelation that led to The Book of the Law. The Sword of Song also contained Crowley’s first manifesto, his first forays into sex magic, his initial embrace of the legendary title of "the Beast," the occult poem "Ascension Day," and mystical essays.

Now in this fully annotated deluxe hardcover edition, renowned Crowley biographer Richard Kaczynski presents Crowley’s preferred text for The Sword of Song, drawing on all existing draft manuscripts as well as unpublished margin notes from Crowley’s personal copies of the book. Kaczynski clarifies all the significant changes and additions throughout the book’s various iterations and provides explanations for the many occult and popular culture references. He also includes a substantial scholarly introduction, reflecting an intimate knowledge of Crowley and the development of his magical practice.

Kaczynski demonstrates how The Sword of Song was not only a prototype for Crowley’s later works such as Konx Om Pax and The Book of Lies, but that The Sword of Song's blend of poetry, allegory, fiction, and essay reveals the formative inner workings of one of the twentieth century’s most provocative thinkers just before he received the life-changing Book of the Law from the discarnate entity Aiwass.

Excerpt

Not a word to introduce my introduction!1 Let me instantly launch the Boat of Discourse on the Sea of Religious Speculation, in danger of the Rocks of Authority and the Quicksands of Private Interpretation, Scylla and Charybdis. Here is the strait; what God shall save us from shipwreck?2 If we choose to understand the Christian (or any other) religion literally, we are at once overwhelmed by its inherent impossibility. Our credulity is outraged, our moral sense shocked, the holiest foundations of our inmost selves assailed by no ardent warrior in triple steel, but by a loathly and disgusting worm. That this is so,3 the apologists for the religion in question, whichever it may be, sufficiently indicate (as a rule) by the very method of their apology. The alternative is to take the religion symbolically, esoterically; but to move one step in this direction is to start on a journey whose end cannot be determined. The religion, ceasing to be a tangible thing, an object uniform for all sane eyes, becomes rather that mist whereon the sun of the soul casts up, like Brocken spectre,4 certain vast and vague images of the beholder himself, with or without a glory encompassing them. The function of the facts is then quite passive: it matters little or nothing whether the cloud be the red mist of Christianity, or the glimmering silver-white of Celtic Paganism; the hard grey dim-gilded of Buddhism, the fleecy opacity of Islam, or the mysterious medium of those ancient faiths which come up in as many colours as their investigator has moods.

If the student has advanced spiritually so that he can internally, infallibly perceive what is Truth, he will find it equally well symbolised in most external faiths.

It is curious that Browning never turns his wonderful faculty of analysis upon the fundamental problems of religion, as it were an axe laid to the root of the Tree of Life. It seems quite clear that he knew what would result if he did so. We cannot help fancying that he was unwilling to do this. The proof 5 of his knowledge I find in the following lines.

I have read much, thought much, experienced much,

Yet would die rather than avow my fear

The Naples’ liquefaction may be false . . .

I hear you recommend, I might at least

Eliminate, decrassify my faith

Since I adopt it; keeping what I must

And leaving what I can—such points as this . . .

Still, when you bid me purify the same,

To such a process I discern no end . . .

First cut the Liquefaction, what comes last

But Fichte’s clever cut at God himself? . . .

I trust nor hand nor eye nor heart nor brain

To stop betimes: they all get drunk alike.

The first step, I am master not to take.6

This is surely the apotheosis of wilful ignorance! We may think, perhaps, that Browning is "hedging" when, in the last paragraph, he says: "For Blougram, he believed, say, half he spoke,"i and hints at some deeper ground. It is useless to say, "This is Blougram and not Browning." Browning could hardly have described the dilemma without seeing it. What he really believes is, perhaps, a mystery.8

That Browning, however, believes in universal salvation, though he nowhere (so far as I know) gives his reasons, save as they are summarised in the last lines of the below-quoted stanza of "Apparent Failure," and from his final pronouncement of the Pope on Guido, represented in Browning’s master piece as a Judas without the decency to hang himself.

So (i.e., by suddenness of fate) may the truth be

flashed out by one blow,

And Guido see, one instant, and be saved.

Else I avert my face, nor follow him

Into that sad obscure sequestered state

Where God unmakes but to remake the soul

He else made first in vain; which must not be.9

This may be purgatory, but it sounds not unlike reincarnation. It is at least a denial of the doctrine of eternal punishment.

As for myself, I took the first step years ago, quite in ignorance of what the last would lead to. God is indeed cut away—a cancer from the breast of truth.

Of those philosophers, who from unassailable premisses draw by righteous deduction a conclusion against God, and then for His sake overturn their whole structure by an act of will, like a child breaking an ingenious toy, I take Mansel10 as my type.i

Now, however, let us consider the esoteric idea-mongers of Christianity, Swedenborg, Anna Kingsford, Deussen11 and the like, of whom I have taken Caird12 as my example. I wish to unmask these people: I perfectly agree with nearly everything they say, but their claim to be Christians is utterly confusing, and lends a lustre to Christianity which is quite foreign. Deussen, for example, coolly discards nearly all the Old Testament, and, picking a few New Testament passages, often out of their context, claims his system as Christianity. Luther discards James. Kingsford calls Paul the Arch Heretic. My friend the "Christian Clergyman" accepted Mark and Acts—until pushed.13 Yet Deussen is honest enough to admit that Vedanta teaching is identical, but clearer! And he quite clearly and sensibly defines Faith—surely the most essential quality for the adherent to Christian dogma—as "being convinced on insufficient evidence." Similarly the dying-to-live idea of Hegel (and Schopenhauer)14 claimed by Caird as the central spirit of Christianity is far older, in the Osiris Myth of the Egyptians. These ideas are all right, but they have no more to do with Christianity than the Metric System with the Great Pyramid. But see Piazzi Smyth!ii Henry Morley16 has even the audacity to claim Shelley—Shelley!—as a Christian "in spirit."

Talking of Shelley:—With regard to my open denial of the personal Christian God, may it not be laid to my charge that I have dared to voice in bald language what Shelley sang in words of surpassing beauty: for of course the thought in one or two passages of this poem is practically identical with that in certain parts of Queen Mab and Prometheus Unbound. But the very beauty of these poems (especially the latter) is its weakness: it is possible that the mind of the reader, lost in the sensuous, nay! even in the moral beauty of the words, may fail to be impressed by their most important meaning. Shelley himself recognised this later: hence the direct and simple vigour of the "Masque of Anarchy."17

It has often puzzled atheists how a man of Milton’s genius could have written as he did of Christianity. But we must not forget that Milton lived immediately after the most important Revolution in Religion and Politics of modern times: Shelley on the brink of such another Political upheaval. Shakespeare alone sat enthroned above it all like a god, and is not lost in the mire of controversy.i This also, though "I’m no Shakespeare, as too probable,"18 I have endeavoured to avoid: yet I cannot but express the hope that my own enquiries into religion may be the reflection of the spirit of the age; and that plunged as we are in the midst of jingoism and religious revival, we may be standing on the edge of some gigantic precipice, over which we may cast all our impedimenta of lies and trickeries, political, social, moral, and religious, and (ourselves) take wings and fly. The comparison between myself and the masters of English thought I have named is unintentional, though perhaps unavoidable; and though the presumption is, of course, absurd, yet a straw will show which way the wind blows as well as the most beautiful and elaborate vane: and in this sense it is my most eager hope that I may not unjustly draw a comparison between myself and the great reformers of eighty years ago.19

I must apologise (perhaps) for the new note of frivolity in my work: due doubtless to the frivolity of my subject: these poems being written when I was an Advaitist and could not see why—everything being an illusion—there should be any particular object in doing or thinking anything. How I have found the answer will be evident from my essay on this subject.i I must indeed apologise to the illustrious Shade of Robert Browning for my audacious parody in title, style, and matter of his Christmas-Eve and Easter-Day. The more I read it the eventual anticlimax of that wonderful poem irritated me only the more. But there is hardly any poet living or dead who so commands alike my personal affection and moral admiration. My desire to find the Truth will be my pardon with him, whose whole life was spent in admiration of Truth, though he never turned its formidable engines against the Citadel of the Almighty.

Product Details

- Publisher: Inner Traditions (June 4, 2025)

- Length: 464 pages

- ISBN13: 9798888501511

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“The Sword of Song is the troubadour’s voice of a young Aleister Crowley pouring ecstatically from the breast of his soul on the threshold of his great awakening. A masterpiece. A symphony. A divine nightingale’s prayer.”

– Lon Milo Duquette, author of The Magick of Aleister Crowley

“‘Post annos CXX patebo.’ Perhaps now that 120 years have passed since the first revelation of Crowley’s elusive collection, The Sword of Song, it can finally open itself to open minds who, like its author, are eager to challenge and find spiritual satisfaction in challenging religious orthodoxies of all kinds. Richard Kaczynski generously provides apposite, revealing, and wholly admirable assistance to help the new reader access the remarkable genius of 666: an oasis in our current desertion of higher things.”

– Tobias Churton, author of Aleister Crowley in England, Aleister Crowley in Paris, and Aleister Crowl

“Aleister Crowley’s The Sword of Song is a wild beast of a book. It includes poetry and prose touching on topics of Buddhism, Kabbalah, Tarot, cosmology, philosophy, agnosticism, magic, and more, but it is skillfully tamed by its editor, Richard Kaczynski, whose erudite introduction and notes shed light on this fascinating product of an original and extraordinary mind. Brimming with insights and ideas that explode on almost every page of the text, this sword truly sings!”

– Gordan Djurdjevic, author of India and the Occult : The Influence of South Asian Spirituality on Mod

“Aleister Crowley’s The Sword of Song, as a discursive and complex conglomerate of poetry, metaphysics, philosophical criticism, and more, has long amazed and puzzled readers. At last, Richard Kaczynski’s fastidious and insightful annotations to this long-awaited volume help to reveal these branches as a unified organic field. This new edition should prove invaluable to the novice as well as the advanced scholar for exploring a new aeon of penetrating vision into magick as it unfolds in our modern era.”

– Robert Podgurski, author of The Sacred Alignments and Sigils: Angelic Magick, Renaissance Thought, a

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Sword of Song 2nd Edition, Deluxe Edition Hardcover 9798888501511