Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

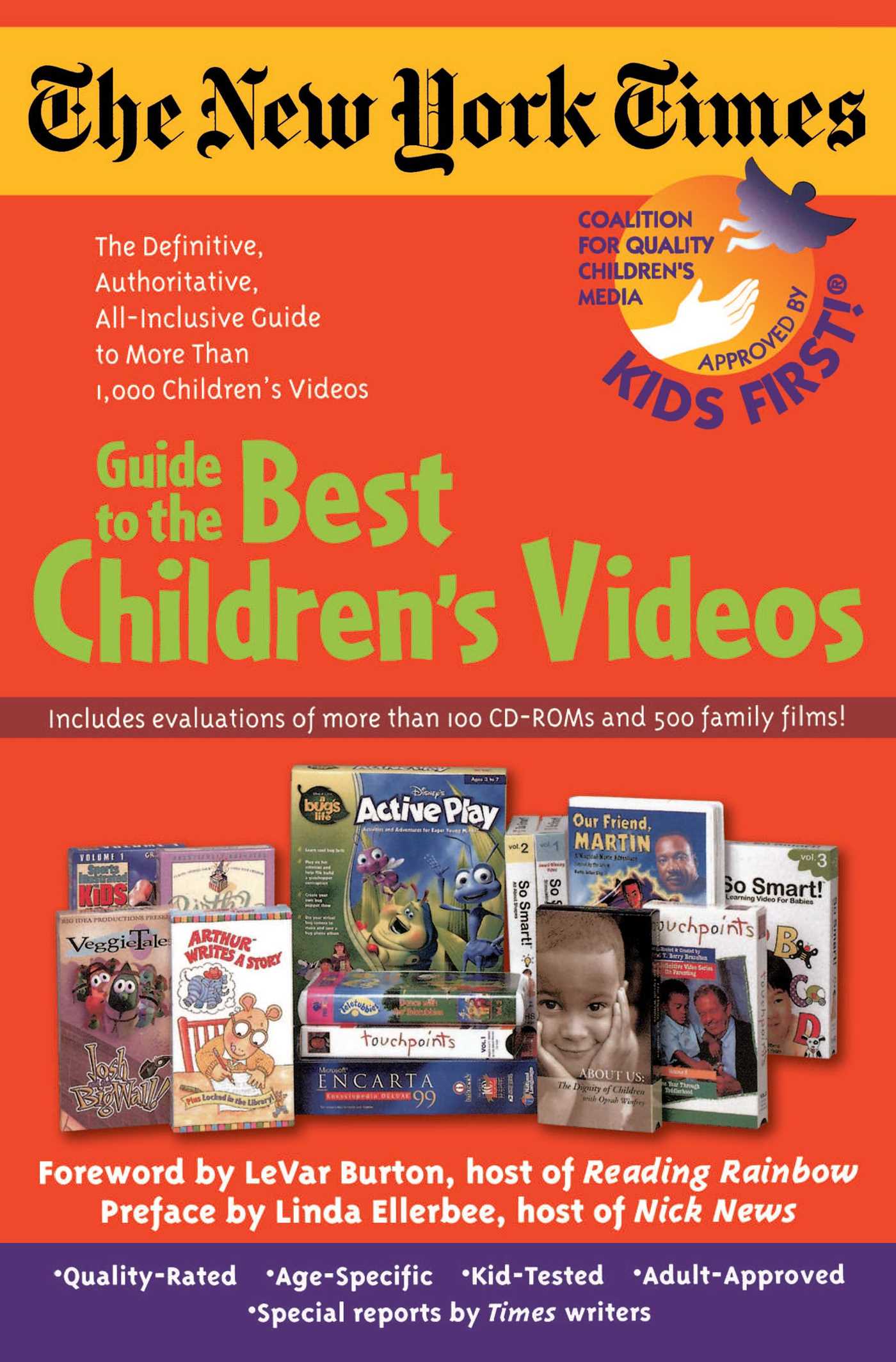

The New York Times Guide to the Best Children's Videos

By Kids First!

Table of Contents

About The Book

The only guide you'll need for choosing the best videos -- and CD-ROMS -- for your family.

INCLUDES:

More than 1000 entries of kid-tested and adult-approved videos currently available.

Listings organized by age -- from infancy to adolescence -- as recommended by child development specialists.

A wide range of categories with special attention to gender and ethnicity: Educatioinal/Instructional; Fairy Tales; Family Literature and Myth; Special Interest; Foreign Language; Holiday; Music; How-To; and Nature.

Review ratings in a clear, easy-to-read format.

Evaluations by panels of adults and children.

Outstanding programs from independents and major studios.

Ordering information, running times, and suggested retail prices.

Evaluations of more than 100 CD-ROMs

500 recommended feature films for the family...and more!

INCLUDES:

More than 1000 entries of kid-tested and adult-approved videos currently available.

Listings organized by age -- from infancy to adolescence -- as recommended by child development specialists.

A wide range of categories with special attention to gender and ethnicity: Educatioinal/Instructional; Fairy Tales; Family Literature and Myth; Special Interest; Foreign Language; Holiday; Music; How-To; and Nature.

Review ratings in a clear, easy-to-read format.

Evaluations by panels of adults and children.

Outstanding programs from independents and major studios.

Ordering information, running times, and suggested retail prices.

Evaluations of more than 100 CD-ROMs

500 recommended feature films for the family...and more!

Excerpt

Chapter One: TV for Girls

Jan Benzel

My daughter Julia quickly discovered a great advantage of learning to read: it allowed her to decipher the television schedule.

Let me stop right here and say for the record that I began parenthood as one of those sanctimonious mothers whose personal goal it was to lower the national TV-watching average among children -- now something like three hours a day -- by turning in a paltry few hours a week for our family. We'd finger-paint! Bake! Read the classics! Go camping!

I soon realized there were big problems with that approach. First, as the parent who walked into a room and turned the TV off, I was very unpopular.

Second, TV -- and video -- have some practical applications from a parent's point of view: Appeasing children left under protest with a new baby-sitter. Distracting children while parents gobble down dinner. Allowing an exhausted parent to take a Saturday afternoon nap (for this, Mary Poppins, at 139 spellbinding minutes, is recommended). And sometimes kids, like adults, just need to escape, cool out, calm down, be entertained.

Then there's the peer-pressure argument. Other kids watch TV. I still remember my own childhood indignity of not knowing the ins and outs of Batman when other third-graders were dissecting the previous night's episode over their peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches. Did I want my daughters to grow up feeling geeky?

Lastly, I didn't enjoy the role of hypocrite. I like TV myself. Batman notwithstanding, I watched television, as much as my parents would allow, and I turned out okay. It's a huge force in American culture. To forbid TV watching in a household is something like ignoring a two-ton elephant sitting in the middle of your living room. Better to approach it with intelligence and care. The forbidden becomes all the more desirable. Fortunately, there's more good programming than ever for children, and it can open up all sorts of windows on the world.

There's public television's rich lineup, from Sesame Street through Bill Nye the Science Guy; Nickelodeon's Nick Jr.; Steven Spielberg's Tiny Toon Adventures, new animation in the classic mode set to vintage rock and roll or symphonic music, with layers of humor to reward different ages; the Disney Channel (despite its endless self-promotions); the nature shows on the Discovery Channel. And once in a while, the networks offer an appealing show, although they've seen their Saturday morning stronghold slip away as Fox, WB, and the cable channels gather steam.

But I still feel some consternation, even when we've narrowed the choice of programs to the best among the flowering proliferation of shows.

When Julia, who is six years old, reads the TV listings, excitedly perusing the possibilities for her precious hour of screen time (not on school nights, reminds her Sanctimonious Mom), these are the names she sees: Winnie the Pooh, Arthur, Rocko's Modern Life, Doug, Charlie Brown, Barney (anathema to anyone over three), and Wishbone. Not so different from what I saw when I devoured TV Guide, that bible to the first generation of TV kids: Popeye, Rocky and Bullwinkle, Daffy Duck, Mickey Mouse, Casper the Friendly Ghost, Dennis the Menace, and Leave it to Beaver. Then and now, it's a boys' club.

Yes, an occasional female character appears on some of these programs, but almost always she's Olive Oyl to Popeye, Lucy to Charlie Brown. Females get second billing if they have a part at all. What's most distressing to me is how early the models emerge. Even in television for the youngest children, from the most enlightened programmers, females have yet to gain a substantial foothold. The creators of Sesame Street, that bastion of diversity, scratched their heads long and hard over creating a female Muppet. Their attempts, including Prairie Dawn, have been feeble at best and never captured the writers' and viewers' imagination the way Elmo, Cookie Monster, Ernie, and Bert have. Why is it that in thirty years, only one girl Muppet, Miss Piggy, made it? At least in the 1950's we had Lassie.

Julia and her sister, Rebecca, who is eight, soak up the subtleties and puzzle over what girls are "supposed" to do when they grow up. Boys absorb the messages too: Girls aren't important, and they don't get to do the fun stuff. Who would you rather be, Jasmine or Aladdin?

In the throes of establishing their elementary school identities, my girls and their friends favor the pithy slogan "Girls rule, boys drool." But there's cognitive dissonance. Their parents and teachers tell them they can do anything they put their minds to. It's true that more of their mothers have careers these days, but what they see still doesn't match what we tell them. We have Madeleine Albright and Janet Reno, but Bill Clinton is in charge. Tom Cruise makes upwards of $20 million a picture; female leads command only a quarter of that. There's a professional women's basketball league, but try to find news of the players on the sports pages. Women's soccer has only just burst upon the scene. The world has changed, but not that much, little girls. Minorities are even less visible than females. It's clear where the power lies.

The primary role of pop culture is not, of course, to be an agent of change. It's a mirror, driven by the demands of its viewers. The reason most often cited for the male dominance on children's television is marketing related: conventional wisdom holds that girls will watch shows about boys, but boys will not watch programs about girls. Throw in a token pink Power Ranger, and girls will tune in. Mark Johnson, who produced the independent film A Little Princess, based on the children's novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett, is still chagrined that although the beautiful, literate movie received critical accolades, it flopped at the box office. "Boys just couldn't bring themselves to say to their friends on the playground: 'Hey, I saw this great movie, A Little Princess,'" he said.

By the time boys get to elementary school, the barrier between the sexes has already been established and is only fortified by the images delivered by the culture. The relentless barrage of commercials, on the networks and most cable channels alike, is the most pointed source of gender distinction: girls are fed pink everything, from baby dolls to nail polish to Barbie CD-ROMs; boys get action figures, which mostly seem to come in putrid shades of green. Neither stereotype holds much appeal.

But there are some challenges to the status quo. The expansion of the television universe -- along with the increasing number of women (and fathers of daughters) among television's creative ranks -- has altered the balance a bit in the last five years. Among the legions of superheroes and boy-centric series, a few females have achieved star billing, especially at off times and in corners of TV that don't depend so much on mass audiences. Many are based on books or otherwise established creations, and there are at least one or two for each age range. Nickelodeon has had hits with Clarissa Explains It All and The Secret World of Alex Mack, both live-action series, now in reruns, that appeal to preteen-agers. The main character in the animated Wild Thornberrys is Eliza, the level-headed daughter of a nature-show host, who travels the world with her family in a van. Girls can have superpowers too: the fourteen-year-old Alex uses hers to help her navigate the shoals of adolescence. For the preschool set, there's Allegra's Window, which addresses the big hurdles of early childhood like surviving the chicken pox, and the new Maisy, an animated series for preschoolers, about the capers of a high-spirited mouse and her friends. HBO has Little Lulu, Pippi Longstocking, and two new series: Dear America, based on Scholastic books that convey history through the eyes of fictional girls and Happily Ever After, fairy tales retold with a feminist twist. Disney offers The Little Mermaid, Madeline, Katie and Orbie, and The Baby-Sitters Club.

Disney, the granddaddy of them all when it comes to entertaining children and now the behemoth of the huge and lucrative children's video market, has had a franchise on female characters, about which much controversy has raged. Movies like Snow White and Sleeping Beauty have drawn Bronx cheers from revisionists and feminists for their female-in-distress-awaiting-their-someday-prince themes. Although a prince of some description is still always in the wings, some of Disney's more recent movies, including Beauty and the Beast, Pocahontas, and Mulan have bona fide heroines who see far more action than their predecessors. Ariel, the Little Mermaid, is among them and continues her underwater adventures in the animated series.

"Girls like adventures as much as boys," Madeline tells Lord Cucuface in The New Adventures of Madeline. Based on the characters from Ludwig Bemelman's books written in the 1930s, the story has been updated. "Children live in a world they don't control, and power is a compelling concept," said Robby London, an executive at DIC Entertainment, which produced the series. "It always has been for boys, and now power is starting to appeal to girls, too." Magical powers are a big draw: Rebecca's must viewing now includes Sabrina, the Teenage Witch on ABC (Two of a Kind, starring Ashley and Mary Kate, the ever-popular Olson twins, is a close second). Sabrina lives with her mother, aunt, and a wisecracking black cat, and spends her time getting in and out of hot water casting spells on her classmates.

Most heartening to me are the shows where boys and girls mix it up, like HBO's Little Lulu, based on Marjorie Buell's 1930s comic strip. "Girls can do everything boys can," Lulu says. "Actually, girls can do everything better than boys. Climb trees, catch fish, throw snowballs. Girls can even eat more grilled cheese sandwiches than boys if they feel like it. Girls are so much better than boys in every way. They just don't go round bragging about it." Ronald Weinberg, executive producer of the series, warmed to Lulu because, he said, she's a free-thinking young woman with a clear idea of where she's going and how she's going to get there. "She's a strong little girl you would like a lot," he said, but added that the series, like the comic strip, would have "as much boy stuff as girl stuff." "Lulu is the star the way Murphy Brown or Lucy were the stars, but she's part of a gang of kids," he added.

Karen Jaffe, the executive director of Kidsnet, a clearinghouse for information about children's television and radio, said children's shows with elements of action, power, or cleverness appeal to both sexes. "Kids like to watch other kids who stay one step ahead of the grown-ups," she said. "If a character is cool, it doesn't seem to matter whether it's a boy or a girl."

Shows like Arthur, Rugrats, and Doug are also in that mold, and the girl characters -- Arthur's friend Francine and little sister D.W., and Doug's friend Patti Mayonnaise -- are often brainy, plucky types. More important, both boys and girls are also pains in the neck, conceited, anxious, athletic, thoughtful, and everything in between. In the adult-role-model department, there is Ms. Frizzle, the wacky science teacher who takes her class on unusual field trips in The Magic School Bus on public television, videos, and CD-ROMs. Lily Tomlin is the voice of Ms. Frizzle, trilling Socratic questions to her charges as they spin in their rattletrap school bus through the solar system, the human body, or anyplace else where they might learn something.

With the potential for more and more channels has come the inevitable news of plans for gender-segregated programming. Fox, who brought the world Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, will splinter its children's programming into a Girlz Channel and a Boyz Channel. Heads are wagging at the prospect of the gender stereotyping, in both programming and commercials, which will probably ensue, at least on those two channels.

I'm not too alarmed. Television these days involves choice, and in children's programming, more choice is a good thing, for girls and boys. I sat and watched my classmates play Little League games. My daughters play soccer, basketball, and softball in leagues of their own. So they'll have a channel of their own. It's far better than being invisible.

Copyright © 1999 by The New York Times

Jan Benzel

My daughter Julia quickly discovered a great advantage of learning to read: it allowed her to decipher the television schedule.

Let me stop right here and say for the record that I began parenthood as one of those sanctimonious mothers whose personal goal it was to lower the national TV-watching average among children -- now something like three hours a day -- by turning in a paltry few hours a week for our family. We'd finger-paint! Bake! Read the classics! Go camping!

I soon realized there were big problems with that approach. First, as the parent who walked into a room and turned the TV off, I was very unpopular.

Second, TV -- and video -- have some practical applications from a parent's point of view: Appeasing children left under protest with a new baby-sitter. Distracting children while parents gobble down dinner. Allowing an exhausted parent to take a Saturday afternoon nap (for this, Mary Poppins, at 139 spellbinding minutes, is recommended). And sometimes kids, like adults, just need to escape, cool out, calm down, be entertained.

Then there's the peer-pressure argument. Other kids watch TV. I still remember my own childhood indignity of not knowing the ins and outs of Batman when other third-graders were dissecting the previous night's episode over their peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches. Did I want my daughters to grow up feeling geeky?

Lastly, I didn't enjoy the role of hypocrite. I like TV myself. Batman notwithstanding, I watched television, as much as my parents would allow, and I turned out okay. It's a huge force in American culture. To forbid TV watching in a household is something like ignoring a two-ton elephant sitting in the middle of your living room. Better to approach it with intelligence and care. The forbidden becomes all the more desirable. Fortunately, there's more good programming than ever for children, and it can open up all sorts of windows on the world.

There's public television's rich lineup, from Sesame Street through Bill Nye the Science Guy; Nickelodeon's Nick Jr.; Steven Spielberg's Tiny Toon Adventures, new animation in the classic mode set to vintage rock and roll or symphonic music, with layers of humor to reward different ages; the Disney Channel (despite its endless self-promotions); the nature shows on the Discovery Channel. And once in a while, the networks offer an appealing show, although they've seen their Saturday morning stronghold slip away as Fox, WB, and the cable channels gather steam.

But I still feel some consternation, even when we've narrowed the choice of programs to the best among the flowering proliferation of shows.

When Julia, who is six years old, reads the TV listings, excitedly perusing the possibilities for her precious hour of screen time (not on school nights, reminds her Sanctimonious Mom), these are the names she sees: Winnie the Pooh, Arthur, Rocko's Modern Life, Doug, Charlie Brown, Barney (anathema to anyone over three), and Wishbone. Not so different from what I saw when I devoured TV Guide, that bible to the first generation of TV kids: Popeye, Rocky and Bullwinkle, Daffy Duck, Mickey Mouse, Casper the Friendly Ghost, Dennis the Menace, and Leave it to Beaver. Then and now, it's a boys' club.

Yes, an occasional female character appears on some of these programs, but almost always she's Olive Oyl to Popeye, Lucy to Charlie Brown. Females get second billing if they have a part at all. What's most distressing to me is how early the models emerge. Even in television for the youngest children, from the most enlightened programmers, females have yet to gain a substantial foothold. The creators of Sesame Street, that bastion of diversity, scratched their heads long and hard over creating a female Muppet. Their attempts, including Prairie Dawn, have been feeble at best and never captured the writers' and viewers' imagination the way Elmo, Cookie Monster, Ernie, and Bert have. Why is it that in thirty years, only one girl Muppet, Miss Piggy, made it? At least in the 1950's we had Lassie.

Julia and her sister, Rebecca, who is eight, soak up the subtleties and puzzle over what girls are "supposed" to do when they grow up. Boys absorb the messages too: Girls aren't important, and they don't get to do the fun stuff. Who would you rather be, Jasmine or Aladdin?

In the throes of establishing their elementary school identities, my girls and their friends favor the pithy slogan "Girls rule, boys drool." But there's cognitive dissonance. Their parents and teachers tell them they can do anything they put their minds to. It's true that more of their mothers have careers these days, but what they see still doesn't match what we tell them. We have Madeleine Albright and Janet Reno, but Bill Clinton is in charge. Tom Cruise makes upwards of $20 million a picture; female leads command only a quarter of that. There's a professional women's basketball league, but try to find news of the players on the sports pages. Women's soccer has only just burst upon the scene. The world has changed, but not that much, little girls. Minorities are even less visible than females. It's clear where the power lies.

The primary role of pop culture is not, of course, to be an agent of change. It's a mirror, driven by the demands of its viewers. The reason most often cited for the male dominance on children's television is marketing related: conventional wisdom holds that girls will watch shows about boys, but boys will not watch programs about girls. Throw in a token pink Power Ranger, and girls will tune in. Mark Johnson, who produced the independent film A Little Princess, based on the children's novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett, is still chagrined that although the beautiful, literate movie received critical accolades, it flopped at the box office. "Boys just couldn't bring themselves to say to their friends on the playground: 'Hey, I saw this great movie, A Little Princess,'" he said.

By the time boys get to elementary school, the barrier between the sexes has already been established and is only fortified by the images delivered by the culture. The relentless barrage of commercials, on the networks and most cable channels alike, is the most pointed source of gender distinction: girls are fed pink everything, from baby dolls to nail polish to Barbie CD-ROMs; boys get action figures, which mostly seem to come in putrid shades of green. Neither stereotype holds much appeal.

But there are some challenges to the status quo. The expansion of the television universe -- along with the increasing number of women (and fathers of daughters) among television's creative ranks -- has altered the balance a bit in the last five years. Among the legions of superheroes and boy-centric series, a few females have achieved star billing, especially at off times and in corners of TV that don't depend so much on mass audiences. Many are based on books or otherwise established creations, and there are at least one or two for each age range. Nickelodeon has had hits with Clarissa Explains It All and The Secret World of Alex Mack, both live-action series, now in reruns, that appeal to preteen-agers. The main character in the animated Wild Thornberrys is Eliza, the level-headed daughter of a nature-show host, who travels the world with her family in a van. Girls can have superpowers too: the fourteen-year-old Alex uses hers to help her navigate the shoals of adolescence. For the preschool set, there's Allegra's Window, which addresses the big hurdles of early childhood like surviving the chicken pox, and the new Maisy, an animated series for preschoolers, about the capers of a high-spirited mouse and her friends. HBO has Little Lulu, Pippi Longstocking, and two new series: Dear America, based on Scholastic books that convey history through the eyes of fictional girls and Happily Ever After, fairy tales retold with a feminist twist. Disney offers The Little Mermaid, Madeline, Katie and Orbie, and The Baby-Sitters Club.

Disney, the granddaddy of them all when it comes to entertaining children and now the behemoth of the huge and lucrative children's video market, has had a franchise on female characters, about which much controversy has raged. Movies like Snow White and Sleeping Beauty have drawn Bronx cheers from revisionists and feminists for their female-in-distress-awaiting-their-someday-prince themes. Although a prince of some description is still always in the wings, some of Disney's more recent movies, including Beauty and the Beast, Pocahontas, and Mulan have bona fide heroines who see far more action than their predecessors. Ariel, the Little Mermaid, is among them and continues her underwater adventures in the animated series.

"Girls like adventures as much as boys," Madeline tells Lord Cucuface in The New Adventures of Madeline. Based on the characters from Ludwig Bemelman's books written in the 1930s, the story has been updated. "Children live in a world they don't control, and power is a compelling concept," said Robby London, an executive at DIC Entertainment, which produced the series. "It always has been for boys, and now power is starting to appeal to girls, too." Magical powers are a big draw: Rebecca's must viewing now includes Sabrina, the Teenage Witch on ABC (Two of a Kind, starring Ashley and Mary Kate, the ever-popular Olson twins, is a close second). Sabrina lives with her mother, aunt, and a wisecracking black cat, and spends her time getting in and out of hot water casting spells on her classmates.

Most heartening to me are the shows where boys and girls mix it up, like HBO's Little Lulu, based on Marjorie Buell's 1930s comic strip. "Girls can do everything boys can," Lulu says. "Actually, girls can do everything better than boys. Climb trees, catch fish, throw snowballs. Girls can even eat more grilled cheese sandwiches than boys if they feel like it. Girls are so much better than boys in every way. They just don't go round bragging about it." Ronald Weinberg, executive producer of the series, warmed to Lulu because, he said, she's a free-thinking young woman with a clear idea of where she's going and how she's going to get there. "She's a strong little girl you would like a lot," he said, but added that the series, like the comic strip, would have "as much boy stuff as girl stuff." "Lulu is the star the way Murphy Brown or Lucy were the stars, but she's part of a gang of kids," he added.

Karen Jaffe, the executive director of Kidsnet, a clearinghouse for information about children's television and radio, said children's shows with elements of action, power, or cleverness appeal to both sexes. "Kids like to watch other kids who stay one step ahead of the grown-ups," she said. "If a character is cool, it doesn't seem to matter whether it's a boy or a girl."

Shows like Arthur, Rugrats, and Doug are also in that mold, and the girl characters -- Arthur's friend Francine and little sister D.W., and Doug's friend Patti Mayonnaise -- are often brainy, plucky types. More important, both boys and girls are also pains in the neck, conceited, anxious, athletic, thoughtful, and everything in between. In the adult-role-model department, there is Ms. Frizzle, the wacky science teacher who takes her class on unusual field trips in The Magic School Bus on public television, videos, and CD-ROMs. Lily Tomlin is the voice of Ms. Frizzle, trilling Socratic questions to her charges as they spin in their rattletrap school bus through the solar system, the human body, or anyplace else where they might learn something.

With the potential for more and more channels has come the inevitable news of plans for gender-segregated programming. Fox, who brought the world Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, will splinter its children's programming into a Girlz Channel and a Boyz Channel. Heads are wagging at the prospect of the gender stereotyping, in both programming and commercials, which will probably ensue, at least on those two channels.

I'm not too alarmed. Television these days involves choice, and in children's programming, more choice is a good thing, for girls and boys. I sat and watched my classmates play Little League games. My daughters play soccer, basketball, and softball in leagues of their own. So they'll have a channel of their own. It's far better than being invisible.

Copyright © 1999 by The New York Times

Product Details

- Publisher: Gallery Books (April 19, 2000)

- Length: 384 pages

- ISBN13: 9780671036690

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The New York Times Guide to the Best Children's Videos Trade Paperback 9780671036690