Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

The Book of Virtues: 30th Anniversary Edition

Table of Contents

About The Book

Help your children develop moral character with this updated, 30th anniversary edition of the perennial classic The Book of Virtues.

Almost 3 million copies of the Book of Virtues have been sold since it was published in 1993. It is one of the most popular moral primers ever written, an inspiring anthology that helps children understand and develop character—and helps parents teach it to them. Thirty years ago, readers thought that the times were right for a book about moral literacy. Back then, Americans worried that schools were no longer parents’ allies in teaching good character. As the book’s original introduction noted, “moral anchors and moorings have never been more necessary.” If that was true in the 1990s, it is even more true today. The explosion of information with the Internet has left many unsure of what is valuable and what is not.

Responsibility. Courage. Compassion. Loyalty. Honesty. Friendship. Persistence. Hard work. Self-discipline. Faith. These remain the essentials of good character. The Book of Virtues contains hundreds of exemplary stories offering children examples of good and bad, right and wrong. Drawing on the Bible, American history, Greek mythology, English poetry, fairy tales, and modern fiction, William J. and Elayne Bennett show children the many virtuous paths they can follow—and the ones they ought to avoid. For the 30th anniversary edition, the Bennetts have slimmed down the book’s contents, while also finding room to introduce such figures as Mother Teresa, Colin Powell, and heroes of 9/11 and the War in Afghanistan. Here is a rich mine of moral literacy to teach a new generation of children about American culture, history, and traditions—ultimately, the ideals by which we wish to live our lives. The updated edition of The Book of Virtues will continue a legacy of raising moral children far into a new century.

Almost 3 million copies of the Book of Virtues have been sold since it was published in 1993. It is one of the most popular moral primers ever written, an inspiring anthology that helps children understand and develop character—and helps parents teach it to them. Thirty years ago, readers thought that the times were right for a book about moral literacy. Back then, Americans worried that schools were no longer parents’ allies in teaching good character. As the book’s original introduction noted, “moral anchors and moorings have never been more necessary.” If that was true in the 1990s, it is even more true today. The explosion of information with the Internet has left many unsure of what is valuable and what is not.

Responsibility. Courage. Compassion. Loyalty. Honesty. Friendship. Persistence. Hard work. Self-discipline. Faith. These remain the essentials of good character. The Book of Virtues contains hundreds of exemplary stories offering children examples of good and bad, right and wrong. Drawing on the Bible, American history, Greek mythology, English poetry, fairy tales, and modern fiction, William J. and Elayne Bennett show children the many virtuous paths they can follow—and the ones they ought to avoid. For the 30th anniversary edition, the Bennetts have slimmed down the book’s contents, while also finding room to introduce such figures as Mother Teresa, Colin Powell, and heroes of 9/11 and the War in Afghanistan. Here is a rich mine of moral literacy to teach a new generation of children about American culture, history, and traditions—ultimately, the ideals by which we wish to live our lives. The updated edition of The Book of Virtues will continue a legacy of raising moral children far into a new century.

Excerpt

The Book of Virtues Introduction

This book is intended to aid in the time-honored task of the moral education of the young. Moral education—the training of heart and mind toward the good—involves many things. It involves rules and precepts—the dos and don’ts of life with others—as well as explicit instruction, exhortation, and training. Moral education must provide training in good habits. Aristotle wrote that good habits formed at youth make all the difference. And moral education must affirm the central importance of moral example. It has been said that there is nothing more influential, more determinant, in a child’s life than the moral power of quiet example. For children to take morality seriously they must be in the presence of adults who take morality seriously. And with their own eyes they must see adults take morality seriously.

Along with precept, habit, and example, there is also the need for what we might call moral literacy. The stories, poems, essays, and other writing presented here are intended to help children achieve this moral literacy. The purpose of this book is to show parents, teachers, students, and children what the virtues look like, what they are in practice, how to recognize them, and how they work.

This book, then, is a “how to” book for moral literacy. If we want our children to possess the traits of character we most admire, we need to teach them what those traits are and why they deserve both admiration and allegiance. Children must learn to identify the forms and content of those traits. They must achieve at least a minimal level of moral literacy that will enable them to make sense of what they see in life and, we may hope, help them live it well.

Where do we go to find the material that will help our children in this task? The simple answer is we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We have a wealth of material to draw on—material that virtually all schools and homes and churches once taught to students for the sake of shaping character. That many no longer do so is something this book hopes to change.

The vast majority of Americans share a respect for certain fundamental traits of character: honesty, compassion, courage, and perseverance. These are virtues. But because children are not born with this knowledge, they need to learn what these virtues are. We can help them gain a grasp and appreciation of these traits by giving children material to read about them. We can invite our students to discern the moral dimensions of stories, of historical events, of famous lives. There are many wonderful stories of virtue and vice with which our children should be familiar. This book brings together some of the best, oldest, and most moving of them.

Do our children know these stories, these works? Unfortunately, many do not. They do not because in many places we are no longer teaching them. It is time we take up that task again. We do so for a number of reasons.

First, these stories, unlike courses in “moral reasoning,” give children some specific reference points. Our literature and history are a rich quarry of moral literacy. We should mine that quarry. Children must have at their disposal a stock of examples illustrating what we see to be right and wrong, good and bad—examples illustrating that, in many instances, what is morally right and wrong can indeed be known and promoted.

Second, these stories and others like them are fascinating to children. Of course, the pedagogy (and the material herein) will need to be varied according to students’ levels of comprehension, but you can’t beat these stories when it comes to engaging the attention of a child. Nothing in recent years, on television or anywhere else, has improved on a good story that begins “Once upon a time . . .”

Third, these stories help anchor our children in their culture, its history and traditions. Moorings and anchors come in handy in life; moral anchors and moorings have never been more necessary.

Fourth, in teaching these stories we engage in an act of renewal. We welcome our children to a common world, a world of shared ideals, to the community of moral persons. In that common world we invite them to the continuing task of preserving the principles, the ideals, and the notions of goodness and greatness we hold dear.

The reader scanning this book may notice that it does not discuss issues like nuclear war, abortion, creationism, or euthanasia. This may come as a disappointment to some. But the fact is that the formation of character in young people is educationally a different task from, and a prior task to, the discussion of the great, difficult ethical controversies of the day. First things first. And planting the ideas of virtue, of good traits in the young, comes first. In the moral life, as in life itself, we take one step at a time. Every field has its complexities and controversies. And so too does ethics. And every field has its basics. So too with values. This is a book in the basics. The tough issues can, if teachers and parents wish, be taken up later. And, I would add, a person who is morally literate will be immeasurably better equipped than a morally illiterate person to reach a reasoned and ethically defensible position on these tough issues. But the formation of character and the teaching of moral literacy come first, in the early years; the tough issues come later, in senior high school or after.

Similarly, the task of teaching moral literacy and forming character is not political in the usual meaning of the term. People of good character are not all going to come down on the same side of difficult political and social issues. Good people—people of character and moral literacy—can be conservative, and good people can be liberal. We must not permit our disputes over thorny political questions to obscure the obligation we have to offer instruction to all our young people in the area in which we have, as a society, reached a consensus: namely, on the importance of good character, and on some of its pervasive particulars. And that is what this book provides: a compendium of great stories, poems, and essays from the stock of human history and literature. It embodies common and time-honored understandings of these virtues. It is for everybody—all children, of all political and religious backgrounds, and it speaks to them on a more fundamental level than race, sex, and gender. It addresses them as human beings—as moral agents.

Every American child ought to know at least some of the stories and poems in this book. Every American parent and teacher should be familiar with some of them, too. I know that some of these stories will strike some contemporary sensibilities as too simple, too corny, too old-fashioned. But they will not seem so to the child, especially if he or she has never seen them before. And I believe that if adults take this book and read it in a quiet place, alone, away from distorting standards, they will find themselves enjoying some of this old, simple, “corny” stuff. The stories we adults used to know and forgot—or the stories we never did know but perhaps were supposed to know—are here. (Quick!—what did Horatius do on the bridge? What is the sword of Damocles? The answers are in this book.) This is a book of lessons and reminders.

In putting this book together I learned many things. For one, going through the material was a mind-opening and encouraging rediscovery for me. I recalled great stories that I had forgotten. And thanks to the recommendations of friends, teachers, and the able prodding of my colleagues in this project, I came to know stories I had not known before. And, I discovered again how much books and education have changed in thirty years. In looking at this “old stuff” I am struck by how different it is from so much of what passes for literature and entertainment today.

Most of the material in this book speaks without hesitation, without embarrassment, to the inner part of the individual, to the moral sense. Today we speak about values and how it is important to “have them,” as if they were beads on a string or marbles in a pouch. But these stories speak to morality and virtues not as something to be possessed, but as the central part of human nature, not as something to have but as something to be, the most important thing to be. To dwell in these chapters is to put oneself, through the imagination, into a different place and time, a time when there was little doubt that children are essentially moral and spiritual beings and that the central task of education is virtue. This book reminds the reader of a time—not so long ago—when the verities were the moral verities. It is thus a kind of antidote to some of the distortions of the age in which we now live. I hope parents will discover that reading this book with or to children can deepen their own, and their children’s, understanding of life and morality. If the book reaches that high purpose it will have been well worth the effort.

A few additional notes and comments are in order. Although the book is titled The Book of Virtues—and the chapters are organized by virtues—it is also very much a book of vices. Many of the stories and poems illustrate a virtue in reverse. For children to know about virtue they must know about its opposite.

In telling these stories I am interested more in the moral than the historic lesson. In some of the older stories—Horatius at the bridge, William Tell, George Washington and the cherry tree—the line between legend and history has been blurred. But it is the instruction in the moral that matters. Some of the history that is recounted here may not meet the standards of the exacting historian. But we tell these familiar stories as they were told before, in order to preserve their authenticity.

Furthermore, I should stress that this book is by no means a definitive collection of great moral stories. Its contents have been defined in part by my attempt to present some material, most of which is drawn from the corpus of Western Civilization, that American schoolchildren, once upon a time, knew by heart. And the project, like any other, has faced several practical limitations such as space and economy (the rights to reprint recent stories and translations can be very expensive, while older material often lies in the public domain). The quarry of wonderful literature from our culture and others is deep, and I have barely scratched the surface. I invite readers to send me favorite stories not printed here, in case I should attempt to renew or improve this effort sometime in the future.

This volume is not intended to be a book one reads from cover to cover. It is, rather, a book for browsing, for marking favorite passages, for reading aloud to family, for memorizing pieces here and there. It is my hope that parents and teachers will spend some time wandering through these pages, discovering or rediscovering some moral landmarks, and in turn pointing them out to the young. The chapters can be taken in any order; on certain days we need reminding of some virtues more than others. A quick look at the Contents will steer the reader in the sought-after direction.

The reader will notice that in each chapter the material progresses from the very easy to the more difficult. The early material in each chapter can be read aloud to, or even by, very young children. As the chapter progresses greater reading and conceptual proficiency are required. Nevertheless we urge younger readers to work their way through as far as possible. As children grow older they can reach for the more difficult material in the book. They can grow up (and perhaps even grow better!) with this book.

Finally, I hope this is an encouraging book. There is a lot we read of or experience in life that is not encouraging. This book, I hope, does otherwise. I hope it encourages; I hope it points us to “the better angels of our nature.” This book reminds us of what is important. And it should help us lift our eyes. St. Paul wrote, “Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is of good repute, if there is any excellence and anything worthy of praise, let your mind dwell on these things.”

I hope readers will read this book and dwell on those things.

I am indebted to Bob Asahina, my able editor at Simon and Schuster, for his encouragement, advice, and usual sober judgment. Sarah Pinckney, also of Simon and Schuster, kept the train running on time with her always-on-target and always-gracious answers, solutions, and suggestions. Robert Barnett, my agent, provided sound counsel and enthusiasm for this venture. My two colleagues in this project deserve special mention. Steven Tigner was judicious, knew where to find things and how best to describe virtues. He promised to help and he did; he’s a man of virtue. As to John Cribb, I cannot thank him enough for his efforts to make this book a reality. Unfailingly and constantly he “mined the quarry” at the Library of Congress, in cartons of old books, in piles of dog-eared magazines. He came to love the stories and the idea of this book. He was “miner,” scout, archivist, researcher, and critic. I owe him a great deal; I am grateful for the example of his friendship.

Finally, my wife, Elayne, always thought this was my book, the one book I had to do. And she was, as usual, right. She read, reviewed, guided, and recommended. As with everything else in my life, this, too, was made better because of her touch. And ironically enough I owe her thanks because on many nights long after I fell asleep, tired from a day of doing a lot of things—including putting this book together—she was the one still awake and reading good stories like these to our boys.

This book is intended to aid in the time-honored task of the moral education of the young. Moral education—the training of heart and mind toward the good—involves many things. It involves rules and precepts—the dos and don’ts of life with others—as well as explicit instruction, exhortation, and training. Moral education must provide training in good habits. Aristotle wrote that good habits formed at youth make all the difference. And moral education must affirm the central importance of moral example. It has been said that there is nothing more influential, more determinant, in a child’s life than the moral power of quiet example. For children to take morality seriously they must be in the presence of adults who take morality seriously. And with their own eyes they must see adults take morality seriously.

Along with precept, habit, and example, there is also the need for what we might call moral literacy. The stories, poems, essays, and other writing presented here are intended to help children achieve this moral literacy. The purpose of this book is to show parents, teachers, students, and children what the virtues look like, what they are in practice, how to recognize them, and how they work.

This book, then, is a “how to” book for moral literacy. If we want our children to possess the traits of character we most admire, we need to teach them what those traits are and why they deserve both admiration and allegiance. Children must learn to identify the forms and content of those traits. They must achieve at least a minimal level of moral literacy that will enable them to make sense of what they see in life and, we may hope, help them live it well.

Where do we go to find the material that will help our children in this task? The simple answer is we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We have a wealth of material to draw on—material that virtually all schools and homes and churches once taught to students for the sake of shaping character. That many no longer do so is something this book hopes to change.

The vast majority of Americans share a respect for certain fundamental traits of character: honesty, compassion, courage, and perseverance. These are virtues. But because children are not born with this knowledge, they need to learn what these virtues are. We can help them gain a grasp and appreciation of these traits by giving children material to read about them. We can invite our students to discern the moral dimensions of stories, of historical events, of famous lives. There are many wonderful stories of virtue and vice with which our children should be familiar. This book brings together some of the best, oldest, and most moving of them.

Do our children know these stories, these works? Unfortunately, many do not. They do not because in many places we are no longer teaching them. It is time we take up that task again. We do so for a number of reasons.

First, these stories, unlike courses in “moral reasoning,” give children some specific reference points. Our literature and history are a rich quarry of moral literacy. We should mine that quarry. Children must have at their disposal a stock of examples illustrating what we see to be right and wrong, good and bad—examples illustrating that, in many instances, what is morally right and wrong can indeed be known and promoted.

Second, these stories and others like them are fascinating to children. Of course, the pedagogy (and the material herein) will need to be varied according to students’ levels of comprehension, but you can’t beat these stories when it comes to engaging the attention of a child. Nothing in recent years, on television or anywhere else, has improved on a good story that begins “Once upon a time . . .”

Third, these stories help anchor our children in their culture, its history and traditions. Moorings and anchors come in handy in life; moral anchors and moorings have never been more necessary.

Fourth, in teaching these stories we engage in an act of renewal. We welcome our children to a common world, a world of shared ideals, to the community of moral persons. In that common world we invite them to the continuing task of preserving the principles, the ideals, and the notions of goodness and greatness we hold dear.

The reader scanning this book may notice that it does not discuss issues like nuclear war, abortion, creationism, or euthanasia. This may come as a disappointment to some. But the fact is that the formation of character in young people is educationally a different task from, and a prior task to, the discussion of the great, difficult ethical controversies of the day. First things first. And planting the ideas of virtue, of good traits in the young, comes first. In the moral life, as in life itself, we take one step at a time. Every field has its complexities and controversies. And so too does ethics. And every field has its basics. So too with values. This is a book in the basics. The tough issues can, if teachers and parents wish, be taken up later. And, I would add, a person who is morally literate will be immeasurably better equipped than a morally illiterate person to reach a reasoned and ethically defensible position on these tough issues. But the formation of character and the teaching of moral literacy come first, in the early years; the tough issues come later, in senior high school or after.

Similarly, the task of teaching moral literacy and forming character is not political in the usual meaning of the term. People of good character are not all going to come down on the same side of difficult political and social issues. Good people—people of character and moral literacy—can be conservative, and good people can be liberal. We must not permit our disputes over thorny political questions to obscure the obligation we have to offer instruction to all our young people in the area in which we have, as a society, reached a consensus: namely, on the importance of good character, and on some of its pervasive particulars. And that is what this book provides: a compendium of great stories, poems, and essays from the stock of human history and literature. It embodies common and time-honored understandings of these virtues. It is for everybody—all children, of all political and religious backgrounds, and it speaks to them on a more fundamental level than race, sex, and gender. It addresses them as human beings—as moral agents.

Every American child ought to know at least some of the stories and poems in this book. Every American parent and teacher should be familiar with some of them, too. I know that some of these stories will strike some contemporary sensibilities as too simple, too corny, too old-fashioned. But they will not seem so to the child, especially if he or she has never seen them before. And I believe that if adults take this book and read it in a quiet place, alone, away from distorting standards, they will find themselves enjoying some of this old, simple, “corny” stuff. The stories we adults used to know and forgot—or the stories we never did know but perhaps were supposed to know—are here. (Quick!—what did Horatius do on the bridge? What is the sword of Damocles? The answers are in this book.) This is a book of lessons and reminders.

In putting this book together I learned many things. For one, going through the material was a mind-opening and encouraging rediscovery for me. I recalled great stories that I had forgotten. And thanks to the recommendations of friends, teachers, and the able prodding of my colleagues in this project, I came to know stories I had not known before. And, I discovered again how much books and education have changed in thirty years. In looking at this “old stuff” I am struck by how different it is from so much of what passes for literature and entertainment today.

Most of the material in this book speaks without hesitation, without embarrassment, to the inner part of the individual, to the moral sense. Today we speak about values and how it is important to “have them,” as if they were beads on a string or marbles in a pouch. But these stories speak to morality and virtues not as something to be possessed, but as the central part of human nature, not as something to have but as something to be, the most important thing to be. To dwell in these chapters is to put oneself, through the imagination, into a different place and time, a time when there was little doubt that children are essentially moral and spiritual beings and that the central task of education is virtue. This book reminds the reader of a time—not so long ago—when the verities were the moral verities. It is thus a kind of antidote to some of the distortions of the age in which we now live. I hope parents will discover that reading this book with or to children can deepen their own, and their children’s, understanding of life and morality. If the book reaches that high purpose it will have been well worth the effort.

A few additional notes and comments are in order. Although the book is titled The Book of Virtues—and the chapters are organized by virtues—it is also very much a book of vices. Many of the stories and poems illustrate a virtue in reverse. For children to know about virtue they must know about its opposite.

In telling these stories I am interested more in the moral than the historic lesson. In some of the older stories—Horatius at the bridge, William Tell, George Washington and the cherry tree—the line between legend and history has been blurred. But it is the instruction in the moral that matters. Some of the history that is recounted here may not meet the standards of the exacting historian. But we tell these familiar stories as they were told before, in order to preserve their authenticity.

Furthermore, I should stress that this book is by no means a definitive collection of great moral stories. Its contents have been defined in part by my attempt to present some material, most of which is drawn from the corpus of Western Civilization, that American schoolchildren, once upon a time, knew by heart. And the project, like any other, has faced several practical limitations such as space and economy (the rights to reprint recent stories and translations can be very expensive, while older material often lies in the public domain). The quarry of wonderful literature from our culture and others is deep, and I have barely scratched the surface. I invite readers to send me favorite stories not printed here, in case I should attempt to renew or improve this effort sometime in the future.

This volume is not intended to be a book one reads from cover to cover. It is, rather, a book for browsing, for marking favorite passages, for reading aloud to family, for memorizing pieces here and there. It is my hope that parents and teachers will spend some time wandering through these pages, discovering or rediscovering some moral landmarks, and in turn pointing them out to the young. The chapters can be taken in any order; on certain days we need reminding of some virtues more than others. A quick look at the Contents will steer the reader in the sought-after direction.

The reader will notice that in each chapter the material progresses from the very easy to the more difficult. The early material in each chapter can be read aloud to, or even by, very young children. As the chapter progresses greater reading and conceptual proficiency are required. Nevertheless we urge younger readers to work their way through as far as possible. As children grow older they can reach for the more difficult material in the book. They can grow up (and perhaps even grow better!) with this book.

Finally, I hope this is an encouraging book. There is a lot we read of or experience in life that is not encouraging. This book, I hope, does otherwise. I hope it encourages; I hope it points us to “the better angels of our nature.” This book reminds us of what is important. And it should help us lift our eyes. St. Paul wrote, “Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is of good repute, if there is any excellence and anything worthy of praise, let your mind dwell on these things.”

I hope readers will read this book and dwell on those things.

I am indebted to Bob Asahina, my able editor at Simon and Schuster, for his encouragement, advice, and usual sober judgment. Sarah Pinckney, also of Simon and Schuster, kept the train running on time with her always-on-target and always-gracious answers, solutions, and suggestions. Robert Barnett, my agent, provided sound counsel and enthusiasm for this venture. My two colleagues in this project deserve special mention. Steven Tigner was judicious, knew where to find things and how best to describe virtues. He promised to help and he did; he’s a man of virtue. As to John Cribb, I cannot thank him enough for his efforts to make this book a reality. Unfailingly and constantly he “mined the quarry” at the Library of Congress, in cartons of old books, in piles of dog-eared magazines. He came to love the stories and the idea of this book. He was “miner,” scout, archivist, researcher, and critic. I owe him a great deal; I am grateful for the example of his friendship.

Finally, my wife, Elayne, always thought this was my book, the one book I had to do. And she was, as usual, right. She read, reviewed, guided, and recommended. As with everything else in my life, this, too, was made better because of her touch. And ironically enough I owe her thanks because on many nights long after I fell asleep, tired from a day of doing a lot of things—including putting this book together—she was the one still awake and reading good stories like these to our boys.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (February 1, 2023)

- Length: 640 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982197117

Browse Related Books

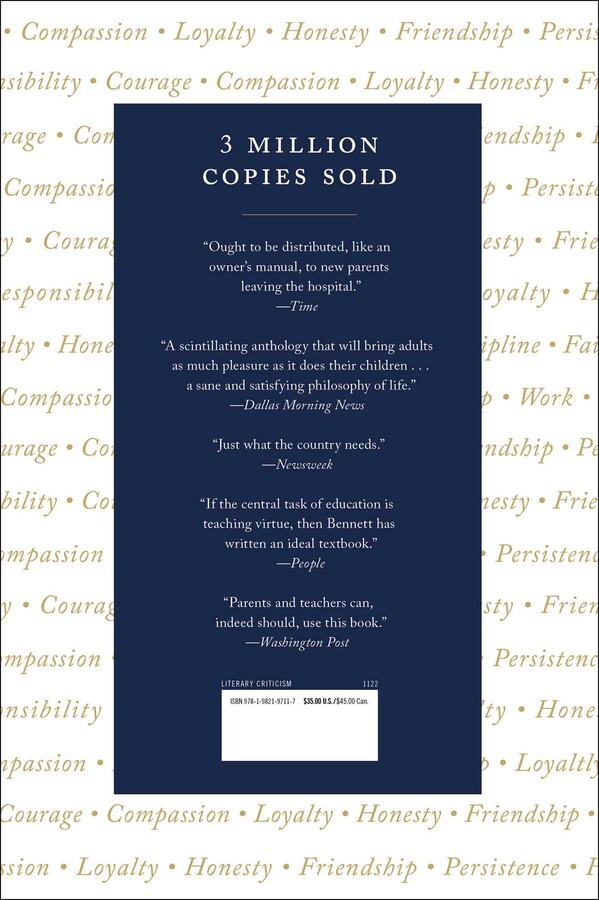

Raves and Reviews

“The Book of Virtues touches the heart—and thereby helps shape the mind. It contains many of the heroic and moral tales that over the years I have grown to love, as well as a great many more that I was delighted to discover for the first time. This is an uplifting and diverting book. Parents will buy it to read to their children and find themselves dipping into it out of pure pleasure.” —Margaret Thatcher

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Book of Virtues: 30th Anniversary Edition Hardcover 9781982197117

- Author Photo (jpg): William J. Bennett Photo Credit:(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit