Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

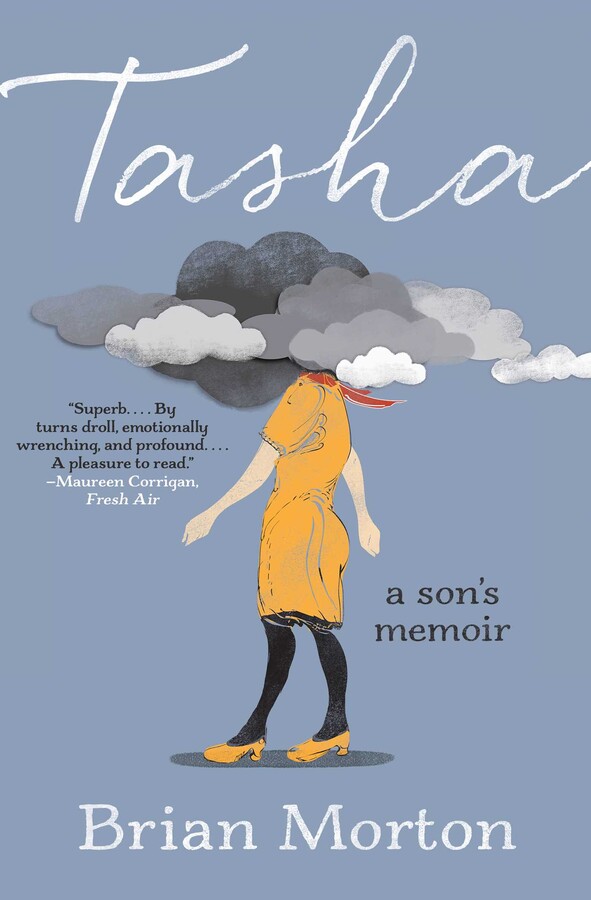

In the spirit of Fierce Attachments and The End of Your Life Book Club, acclaimed novelist Brian Morton delivers a “superb” (Maureen Corrigan, Fresh Air), darkly funny memoir of his mother’s vibrant life and the many ways in which their tight, tumultuous relationship was refashioned in her twilight years.

Tasha Morton is a force of nature: a brilliant educator who’s left her mark on generations of students—and also a whirlwind of a mother, intrusive, chaotic, oppressively devoted, and irrepressible.

For decades, her son Brian has kept her at a self-protective distance, but when her health begins to fail, he knows it’s time to assume responsibility for her care. Even so, he’s not prepared for what awaits him, as her refusal to accept her own fragility leads to a series of epic outbursts and altercations that are sometimes frightening, sometimes wildly comic, and sometimes both.

Clear-eyed, “deeply stirring” (Dani Shapiro, The New York Times Book Review), and brimming with dark humor, Tasha is both a vivid account of an unforgettable woman and a stark look at the impossible task of caring for an elderly parent in a country whose unofficial motto is “you’re on your own.”

Excerpt

On March 13, 2010, driving at night in a thunderstorm, my mother got stuck on a flooded road near the Hackensack River. Her car stalled out and the electrical system failed, so pressing on the horn yielded no sound. She didn’t have her cell phone with her. The river forced its way inside the car, covering her ankles, moving up to her knees. She was eighty-five years old and in poor health and she knew that if she left the car she’d be dragged down into the water. She was sure she was going to die.

I was living with my family in Westchester. The rain had been crazy all day. In the morning I’d promised my kids that we’d go out to the toy store and the library, but although we wouldn’t have to travel more than half a mile, the storm was so wild that I grew doubtful about leaving the house at all. Heather was at a conference that weekend, and I had the kids on my own. Finally I told myself it couldn’t be so terrible to drive a few blocks, and I took them to the toy store. Driving there turned out to be an exercise in not letting them see how frightened I was—I could barely make out the road—and after they’d each picked a toy, I decided to skip the library and take them back home.

My niece, who was in high school, was giving a dance recital that night, but the drive took an hour in good conditions and would have been a nightmare during a storm like this. I wrote to my sister, Melinda, with apologies; she told me it was fine, and added that our mother was still planning to attend.

I can’t say I was surprised. My mother was like a child in many ways. She’d never been good at knowing her own limitations or thinking ahead. One of my early memories was of an evening when she took Melinda and me to see our grandparents off at Penn Station after they’d visited us in New Jersey. I was four and my sister was seven. Our grandparents were taking a train back to Pittsburgh. She felt it important to help them find their seats, though they were only in their early sixties and were perfectly capable of doing this themselves, and she felt it important to stay with them, soaking up every minute of togetherness, even after the announcement that anyone without a ticket had to leave the train. She told my sister and me to get off and wait for her on the platform. I don’t know what made her want to postpone leaving until the last possible moment. I don’t think there was any real reason; I think it was just hard for her to leave. That was one of the first things you got to know about my mother, if you knew her at all. It was hard for her to let anybody go.

My sister and I waited outside the train. We heard a second announcement, and then a third, and then we saw the train start to move.

I don’t remember what I was thinking. I don’t remember if my sister said anything. But I do remember that the train began moving and my mother wasn’t with us and I didn’t know what we were going to do.

Finally she emerged in the space between two cars. She looked at us, smiled nervously, looked down at the swiftly moving platform, and jumped.

My mother, it should be mentioned here, was not a graceful woman. She’d never been athletic, and a providential moment of nimbleness was not bestowed upon her now. She leapt from the train in an odd way—the position of her body reminded me of an angel in a cartoon, reclining on a cloud while playing a harp—and landed heavily on the platform, and cried out in pain.

At the distance of sixty years, I can see that she was lucky. The force of the fall was taken by the fleshiest part of her body. She didn’t break any bones. She didn’t hit her head. She didn’t suffer any serious injuries. But for months she bore a frightening bruise, covering most of her thigh and part of her backside. (She showed it to us more than once, even though, for me at least, once was more than enough. She might have thought it was educational for us in some way.)

To my four-year-old mind, this adventure seemed to say two things about her. Her leap and her bruise seemed to mark her as both heroic and unbalanced. I can’t deny that I thought there was something glorious about the sight of her leaping from the train, but neither can I deny that I understood, even then, that there was something off about it too, something that set her apart from other grown-ups, and not in a good way.

All of which is to say that in 2010, when I learned my mother was planning to attend the recital, it didn’t even occur to me to try to talk her out of it. I thought it was foolish, but I also thought it was just her, and I’d learned long ago that when I tried to talk her out of doing something she was intent on, I had no chance.

I did whatever I did with the kids that night. I imagine I made them some nutritionally questionable dinner—chicken fingers for Emmett, mac and cheese for Gabe—and watched a movie with them and waited eagerly for them to fall asleep. After that I’m sure I either wrote or wasted time on the internet. The storm didn’t die down. If you care to look it up, just search for “storm” and “March 13, 2010” and “New Jersey.” I remember that I thought about my mother once or twice, wondering how she’d fared in the miserable weather. I wrote her an email at around midnight, and was surprised when I didn’t hear back—she liked to stay up late, and she was always on her computer—but I have to admit I didn’t think about it very much. I assumed things had turned out fine.

In the morning I checked my email and saw that she’d written to me at two. She told me what had happened—she’d finally been found by the police as they patrolled the flooded streets—and said that it had been the worst night of her life.

A few days later, Melinda visited her and noticed that her balance was off. She took her to her doctor, who sent them to Englewood Hospital to determine whether she’d had a stroke.

I met them at the hospital. My mother had already had a few tests and they were waiting for results. She was sitting in one of those backless gowns, which seem designed to humiliate you and thereby render you willing to do what you’re told. She was normally an irrepressibly chatty person, but now she was sitting on the examining room table with a doleful expression, not saying a word. Occasionally she swung her legs in the air, looking like a disappointed child.

When she did speak, it was hard to tell if she was slurring her words. If you listen carefully to anyone at all and ask yourself whether they’re slurring their words a little, it can be hard to be sure.

I was worrying about many things.

I was worrying about her, of course. I was worrying about how much damage she might have suffered; I was worried about whether she was going to be able to continue living on her own. But I was also worrying about myself. I had successfully kept her at arm’s length for many years, not really doing much for her except having dinner with her from time to time, and this was comfortable for me. Now it seemed that I might have to call on different capacities in myself, and I didn’t want to.

Reading Group Guide

Join our mailing list! Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Introduction

In an effort to preserve his relationship with his mother, Tasha—willful, meddlesome, wickedly funny—Brian had long held her at a distance. But when Tasha’s faculties begin to decline as she reaches the end of her life, her son must reckon with his responsibility to the woman who one night left him twenty-seven voicemails . . . when he was in his late twenties. Tasha is Brian’s tribute to a whip-smart woman who could be as outrageous as a Philip Roth character, as well as an unsparing account of caring for her in a country that offers little support for the elderly or the people invested in their well-being. In precise and unsentimental prose, Brian knits together family lore, meditations on masculinity, and anecdotes that are uproarious and upsetting in equal measures to paint a truthful portrait of his mother: the first-ever copy girl at the Daily Worker, a revolutionary educator, and the woman who, when she left her Bronx home at age sixteen, changed her name from Esther to Tasha. For readers of Bettyville and The End of Your Life Book Club, this memoir is a poignant depiction of what mothers teach their sons in life and death.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. In the first few chapters, Brian introduces us to his mother as well as to his perception of her, writing that Tasha is an endeavor “to try to see her whole, as I didn’t succeed in doing when she was alive” (p. 15). Beginning with this radical honesty, in what ways does Brian’s portrait of Tasha expand and complicate as the book progresses?

2. Teaneck is a “bedroom community” that boasts a history of progressive policies and community engagement, and Tasha is a “patriot” of the town (p. 39). How does her deep commitment to Teaneck and the people in it shape our understanding of her character?

3. As crabby as Tasha could be, she was quick to form both brief and enduring kinships with people who came into her life: Amelia (her father’s mistress), Naomi (Brian’s former student and her companion at Gabe’s birthday party), and Cece (her morning aide at Van Buren), to name a few. Which relationship do you find the most affecting?

4. Do you agree with Brian’s claim that it’s more difficult for a man to identify with his mother than his father, or do you think that this thinking is a vestige of another era, as he concedes might be the case (p. 65)?

5. The eighteenth-century Dutch Colonial in which Tasha lived for decades in mounting squalor is almost a character in itself, trapping her while paradoxically serving as a point of pride indicative of independence (in her mind, at least). If you were in Brian’s shoes, how would you have dealt with the question of Tasha’s house, both when she was alive and after she passed?

6. When Marcia, the Five Star Residence representative, invokes the word community during her conversation with Tasha, Brian uses this moment as a time to reflect on what that word means in theory and practice (pp. 88–90). What are some different examples of community in Tasha?

7. In some ways, the tone of Brian’s prose evolves as Tasha the person and Tasha the book near their ends. Can you identify certain places in the text where you noticed a shift in the tenor of the narrative?

8. Brian offers many scenes and stories to illustrate the kind of person Tasha was: two dead mice in the living room (p. 22); an argument over angel cake that ends in a tearful embrace (p. 40); a slow but steady escape from the Five Star Residence tour (pp. 92–95). What is your favorite Tasha anecdote, and why?

9. There is also a trove of Tasha quips from which to choose: “Brian? This is your former mother . . .” (p. 9); “Eighty-six is just a kid!” (p. 77); “You wouldn’t be here if not for me” (p. 144). Which is your favorite, and why?

10. For readers who have never experienced caring for an aging parent: Why do you think Brian felt moved to share his experience, and what did you learn from it? Did you begin reading with expectations about how the story would unfold? Were there moments and decisions throughout the book that surprised you?

11. For readers who have experienced caring for an elderly parent: What did you appreciate about Brian’s depiction, and is/was your experience similar or different? How so?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. The original title of Tasha was The Woman Who Leapt from the Train, after the scene in which Tasha does just that (pp. 2–3). Split up and brainstorm alternative titles, then come together to make a case for your favorite in front of the wider group.

2. Write down a list of other memoirs that deal in parent-child relationships, end-of-life care, motherhood, small-town life, or the lives of the elderly. Using these works as means to compare and contrast, consider how style and content affect your readings of these topics. What did you appreciate about Brian’s approach?

3. Imagine you are on the casting team for a film based on Tasha. Who would play Tasha, Brian, Heather, and Melinda? What about more minor characters like Dick, Sigismund Laster, Rabbi Zierler, and Winnie?

A Conversation with Brian Morton

Tasha is your first memoir after having published five novels. What are some challenges of the genre that you had not yet encountered as a novelist?

Weirdly, while I was writing the book, I wasn’t thinking about the challenges posed by a different genre. I was feeling a lot of freedom and ease.

When I write a novel, I feel as if I’m trying to give birth to a whole cast of characters and everything that goes along with them—their life histories, their worldviews, their clothes, their apartments, their pets. With Tasha, the stories were all there in my memory, ripe for the taking. Remembering felt easier than imagining usually does.

You wrote a version of your mother in The Dylanist, and in Florence Gordon the titular character is a strong-willed, independent seventy-five-year-old. How did those experiences inform how you wrote the Tasha that appears in Tasha?

In Tasha, I talk about how I painted an almost purely comic picture of her in The Dylanist. I wanted to paint a fuller portrait of her this time around. That was important to me.

About Florence Gordon—I didn’t see any similarity to Tasha when I was writing the Florence book, and I didn’t see any similarity to Florence when I was writing the Tasha book. But at one point during the editing process with Tasha, Lauren Wein, who was my editor for both books, underlined this sentence: “Old, frail, disoriented, she nevertheless retained an unbendable intensity of sheer will, trained on the one clear goal of living her own life.” And she made a note that said something like, “Remind you of anyone?” I still think Tasha and Florence are more different than they’re alike, but this helped me see that Tasha and Florence had more in common than I’d realized. And that maybe, in writing about Florence several years ago, I was getting ready to write about Tasha.

There is a tremendous specificity to Tasha, especially in the barbed banter that so defines Tasha as a character. How did you ensure a truthful portrayal of past events?

My mother was very quotable, so a lot of the things she says in the book are things I remember her saying. But my main goal was to try to re-create the feeling of what talking to her was like.

Tasha is relatively slim, yet it feels complete. Is there a story or character that you wanted to include but ended up omitting? If so, why? And if not, is there anything you wish you’d had more room in the narrative to explore?

The older you get, the more you appreciate short books. At least that’s how it’s been with me. Part of the fun of writing Tasha was trying to tell a story that felt complete in very few pages. So I was happy to try to be suggestive rather than exhaustive.

While Tasha is of course the central figure in the book, your family members and other minor characters populate the periphery. What decisions do you make when attempting to encapsulate a whole person in a few sentences?

Well, first of all, I object to your calling my family members minor characters!

That said, I knew from the beginning that this book was going to focus closely on my mother and on my relationship with her, but I didn't want to give the impression that I was taking care of her all by myself. So I felt it was important to try to make everybody else who came into the book as memorable as possible.

And also, it’s probably just a novelist’s habit. The habit of trying to illustrate how everyone is the center of a world. The habit of remembering that no one is a minor character in their own life. I had a student at Sarah Lawrence who put it well. He said that when he writes about minor characters, he wants to do it in a way that shows that each of them deserves their own spin-off.

And finally, maybe it was a way of honoring what I wrote about as Tasha’s attitude toward life—“her belief that everyone is equal and we’re all in this together.”

As you were developing and writing Tasha, did you turn to any other books or media that inspire you? If so, what are they and how did they influence you?

Rereading Philip Roth’s Patrimony, his memoir about his father, was helpful. After I started thinking about writing about my mother, I felt stymied for a while, because trying to choose among all my memories felt overwhelming. Finally, things got clearer when I decided to focus entirely on the last five years of her life. Sometime after I decided to do it this way, I picked up Patrimony, which I’d liked when I read it shortly after its publication in 1991, but which I didn’t remember. I’d forgotten how tightly Roth focused on a very short period of time. It reassured me that you could convey a sense of a loved one’s long life by writing about a brief, intense corner of it.

Is there a scene or section in Tasha of which you are especially proud or fond?

I suppose I’m fondest of the section in which she takes over the narration, because it was the scene that most completely took me by surprise. I had no idea it was coming.

The most stylistically and tonally divergent part of Tasha is when you reflect on her last words and then embody her voice in a stream-of-consciousness tirade. In what ways do you imagine this passage contributes to Tasha and its purpose?

When I wrote the section, I felt almost as if I were channeling her. It wasn’t premeditated, and I had no idea why I was writing it. But all through the process of working on the book, I’d been worrying about whether I was representing her fairly, seeing her as she really was. Eventually I came to think that this chapter (along with the section in which I include some passages from her diaries) was the closest I could come to letting her speak in her own voice.

If you could guarantee that readers think more deeply about one idea or concept in your book, what would it be and why?

At first I was going to answer this by saying something about the scandal of eldercare in the United States, or about the relationships of mothers and sons. But really, my hope is just that readers will feel as if they spent a little time with Tasha. My hope is that when they finish the book, they’ll feel like they knew her.

Product Details

- Publisher: Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster (August 16, 2023)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982178949

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“I found Tasha addictive. I couldn’t even slow down. Why? Its startling details, fearless depictions and the curiosity this sparks: How might Morton “solve” the unsolvable?”… Tasha stands as both a cri de coeur and vibrant testament—the painstaking, brave, generous piecing-together of a wildly difficult puzzle.” —Joan Frank, The Washington Post

“Superb… one thing that sets Tasha far apart from the usual one-sided literary conversation with a deceased parent is Morton's rigorous attempt to see his mother, Tasha, whole — as a person. Another thing that distinguishes Tasha is Morton's elastic style as a writer, by turns droll, emotionally wrenching, and profound. … [A] powerful memoir… Tasha is such a pleasure to read, oscillating between past and present, horror and hilarity, the big social picture and one son's ongoing attempt to work out some stuff with his mother.” —Maureen Corrigan, Fresh Air

“Brian Morton, a gifted, compassionate novelist, has, over the course of five elegant novels, explored the moral complexity inherent in storytelling. … With humility and grace, he tells us that he has failed his mother by not seeing her as a full and complete person, one with great courage, complexity and strength. But it is a gift of mature adulthood — and perhaps the work of writing memoir — to see our parents as people who exist outside of their centrality in our lives… [a] lucid memoir.” —Dani Shapiro, The New York Times

“Morton’s affecting, funny tribute captures the complexities of the mother-son bond, the crazy-making choices of caretaking and the mixed blessings of small-town life.”—People

"Unstinting yet tender… a tour de force... Part gut-punch comedy, part eulogy, this tribute is dazzling” —Publishers Weekly *starred review*

"One of the truest, most insightful mother-child memoirs I have ever read.” —Vivian Gornick, author of Fierce Attachments

"This profoundly moving memoir is both an absolute delight and a punch to the gut: Brian Morton writes without flinching about his often exasperating mother, his own considerable failings, and the impossible demands of balancing safety and independence, love and anger, guilt and grief. I urge you to read this astonishing work: part family comedy, part prayer for the dead, and wholly unforgettable —like Tasha herself." —Will Schwalbe, author of The End of Your Life Book Club

“A searing and tender memoir, written with candor, warmth, and heartbreaking grace.” —Betsy Lerner, author of The Bridge Ladies

"Yes, Tasha is an indelibly memorable character, but what makes the book really soar is the combination of her plus the author's truthful self-portrait: the two are locked in a pas de deux, for better or worse, that epitomizes the impossible-to-satisfy love of mother and child." —Phillip Lopate

“Empathic, elegantly written… Morton’s sharp condemnation of the lack of national eldercare propels Tasha, but its real animating force is his psychological insight and generous spirit.” —The National Book Review

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Tasha Trade Paperback 9781982178949