Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

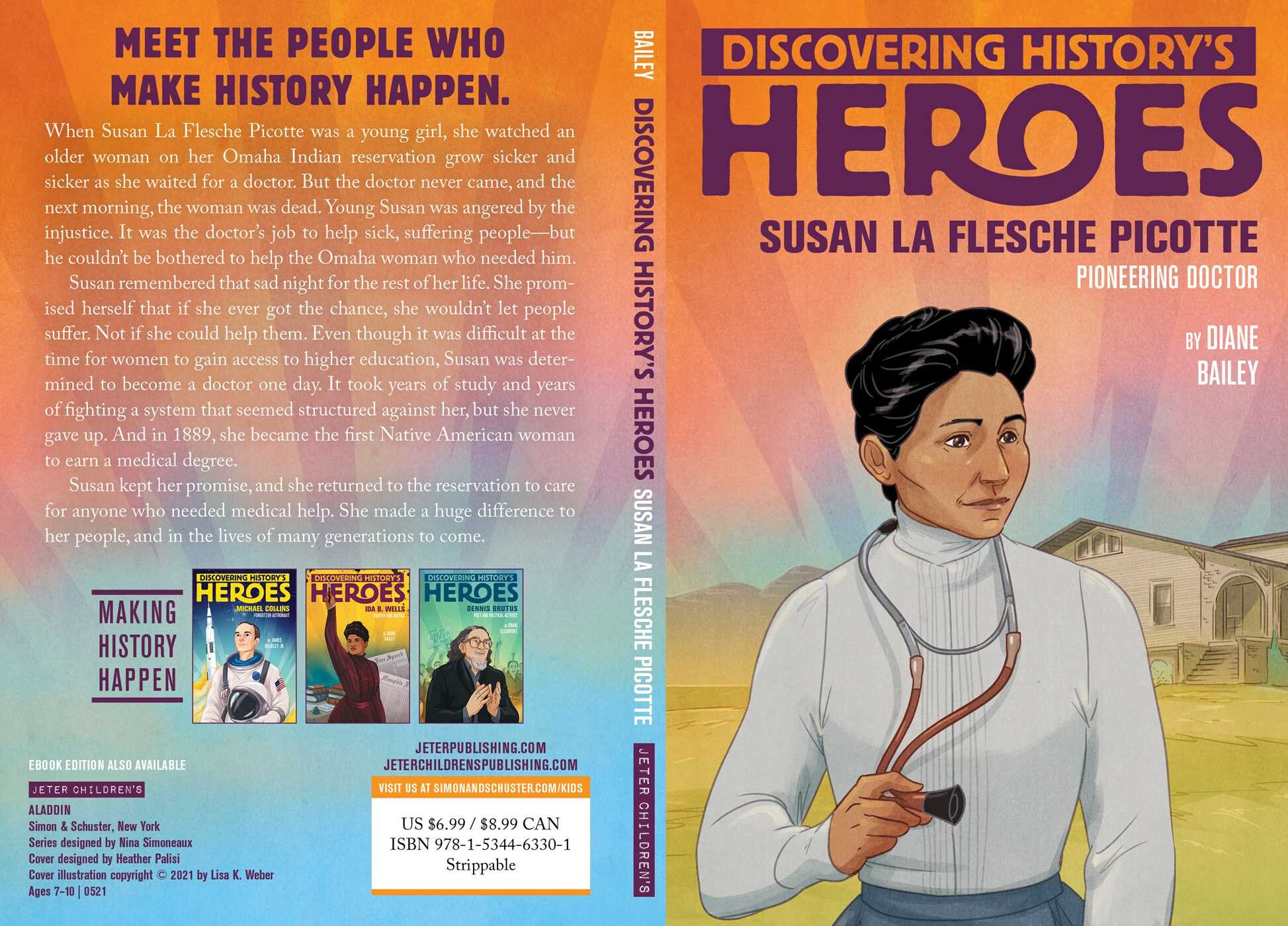

Jeter Publishing presents a series that celebrates men and women who altered the course of history but may not be as well-known as their counterparts. In this middle grade biography, learn about Susan LaFlesche Picotte, the first Native American woman to earn a medical degree.

Susan LaFlesche Picotte was the first Native American doctor in the United States and served more than 1,300 patients over 450 square miles in the late 1800s.

Susan was the daughter of mixed-race (white and Native American) parents, and struggled much of her life with trying to balance the two worlds. As a child, she watched an elderly Omaha Indian woman die on the reservation because no white doctor would come help. When she grew older, Susan attended one of just a handful of medical schools that accepted women, graduating top of her class as the country’s first Native American physician.

Returning to her native Nebraska, Susan dedicated her life to working with Native American populations, battling epidemics from smallpox to tuberculosis that ravaged reservations during the final decades of the 19th century.

Blizzards and frigid temperatures were just part of the job for Susan, who took her horse and buggy for house calls no matter what the weather conditions. Before her death in 1915, she also established public health initiatives and even built a hospital.

Susan LaFlesche Picotte was the first Native American doctor in the United States and served more than 1,300 patients over 450 square miles in the late 1800s.

Susan was the daughter of mixed-race (white and Native American) parents, and struggled much of her life with trying to balance the two worlds. As a child, she watched an elderly Omaha Indian woman die on the reservation because no white doctor would come help. When she grew older, Susan attended one of just a handful of medical schools that accepted women, graduating top of her class as the country’s first Native American physician.

Returning to her native Nebraska, Susan dedicated her life to working with Native American populations, battling epidemics from smallpox to tuberculosis that ravaged reservations during the final decades of the 19th century.

Blizzards and frigid temperatures were just part of the job for Susan, who took her horse and buggy for house calls no matter what the weather conditions. Before her death in 1915, she also established public health initiatives and even built a hospital.

Excerpt

Chapter 1: Born with the Buffalo 1. BORN WITH THE BUFFALO

In June 1865, the Omaha Indians were on the move. They had planted their crops, and in the fall the tribe would return to their reservation to harvest corn, squash, beans, and melons. For a few weeks during the summer, though, they were traveling across the plains, camping in their teepees, hunting for buffalo. The Omaha way of life depended on the buffalo. The animals’ meat would feed the tribe through the winter, and their furry coats would become warm blankets and robes. Their skin was turned into moccasins and teepee coverings.

In the past, millions of buffalo had roamed the Nebraska prairie. But those herds were dwindling as white men moved into the Great Plains and killed the buffalo. Sometimes it was for food, but more often it was just for sport. Joseph La Flesche, who was also called “Iron Eye,” was chief of the Omaha tribe. He feared there weren’t many years left when his people would be able to go on their annual summer hunt. What would happen then?

As these problems stood before the Omaha, though, good news spread through the camp. On June 17, Iron Eye’s wife Mary (also known as “One Woman”) gave birth to a baby girl. For a little while Joseph set aside his worries. Right now it was time to greet his new daughter.

Susan La Flesche was born into a big, close family. She already had three older sisters: Susette was eleven, Rosalie was four, and Marguerite was three. (A brother, Louis, had been born in 1848 but had died.)

Joseph also had a second wife, which was common among the Omaha people. From this marriage Susan had a half brother named Francis, who was seven when Susan was born. Her half sister, Lucy, was born the same year as Susan. Another half brother, Carey, came in 1872, the year Susan turned seven.

As soon as she was old enough, Susan was expected to help the family in any way she could. She learned how to plant and harvest crops, and how to dry strips of buffalo meat.

One of her jobs was to carry water from the spring to the house. Susan dreaded that chore! It was a long walk, barefoot over the rough grass, with the sun beating down on her back. And the buckets were heavy!

But there was plenty of time to play, too. Everyone laughed during the dance of the turkeys, when the children imitated the funny way turkeys poked their necks out. Other times the kids stared at one another until someone cracked a smile. Whoever smiled first lost the game—and got water poured over their head. Susan and her sisters played house in teepees that they built, taking care of dolls made from corncobs and dressed in bits of calico fabric. The sisters rode across the Nebraska prairie on stick ponies they made from the tall stalks of sunflowers.

Like all other Omaha children, Susan behaved respectfully around her parents and other adults. She knew it was rude to walk in between a person and the flap of the tent, and she knew not to stare at people—especially strangers! She learned to get up quietly, without drawing attention to herself. Of course she never interrupted when the grown-ups were talking. And from the time Susan was a little girl, the grown-ups were always talking. Big changes were happening on the reservation, and more changes were coming.

Joseph had become chief of the Omaha in 1853. By then, thousands of white people had been moving onto Indian lands. Joseph had seen how the US government had helped these settlers take over the land of other Indian tribes. He knew that the United States wanted the Omaha’s land too. Joseph worried that if the Omaha did not surrender their land voluntarily, the US government might take it by force. The Omaha were a small tribe, and not very powerful. They would not be able to stop the strong US military.

Joseph believed that for his tribe to have a peaceful, productive future, they needed to find a way to live alongside white men—not fight against them. So in 1854 he signed a treaty between the Omaha and the US government. Under the agreement, the Omaha sold the United States millions of acres of land that were their traditional hunting lands. In return, the Omaha got to keep living on a small piece of land, about 300,000 acres, that was nestled on the banks of the Missouri River in northeastern Nebraska. This was now the Omaha reservation.

However, the US government made sure they had a lot of power over the Omaha. The treaty made it clear that the Omaha were to use their reservation land in ways that white men approved of—namely, farming. Although the Omaha were used to raising a few crops, the US government wanted them to take up full-time, large-scale farming, like white men did. According to the treaty, the government didn’t even have to pay the Omaha the money they were owed from the sale of their hunting grounds. Instead, the United States could decide to use the money on programs for the “moral improvement and education” of the Omaha, or for starting farms and buying supplies. In return, the government helped the Omaha set up a mill, for grinding corn and flour, and a blacksmith shop to take care of their equipment. Finally, the US military promised to protect the Omaha from other Indian tribes such as the Sioux, who had been enemies of the Omaha for a long time. To make sure things were done the way the US government wanted, officials established an office on the reservation, called an agency, to take care of things.

Many of the Omaha opposed Joseph’s decision to cooperate with the United States. He had sold almost all the Omaha’s lands. How could they go on their annual hunts, which were so important to the tribe? Joseph sympathized with them, but he was their chief. He insisted that he’d done the right thing.

Joseph started to adopt the ways of white men. In the past the Omaha had lived in earth lodges or teepees. But white men lived in wooden houses with square corners and glass panes in the windows. In 1857, Joseph built a wooden house for his family. It was the first one on the reservation. He planted crops and kept cattle, just like white men. He also joined the Presbyterian Church, which established a mission on the reservation to spread the Christian religion among the Indians. Some Omaha followed Joseph’s lead and built their own wooden houses. But others refused. They mocked what they called the Village of the Make-Believe White Men.

Joseph was proud of his Indian heritage, and he wanted his children to be proud of it too. But he also wanted them to fit into the white man’s world. That meant making some changes. For example, Joseph and Mary gave their oldest daughter a traditional Indian name that meant “Bright Eyes,” but they also gave her an English name, Susette. The rest of the children, including Susan, got only English names. Because Susan and her sisters were daughters of a chief, normally they would have received tattoos to show their status. Not now. Joseph did not want them to look different.

Still, Susan grew up knowing how to speak Omaha as well as English, and understanding the traditions of her people. Many evenings her grandmother would come by the house and tell a story. Susan loved to listen to funny tales of rabbits who played tricks, or to silly explanations for why turkeys have red eyes. Sometimes the stories had a message. The Omaha were patient, cautious people. They did not rush into things. The stories explained that before making a big decision, “the people thought.”2

And so Susan grew up with a foot in two worlds—one Omaha, one white.

Both of them made her think.

In June 1865, the Omaha Indians were on the move. They had planted their crops, and in the fall the tribe would return to their reservation to harvest corn, squash, beans, and melons. For a few weeks during the summer, though, they were traveling across the plains, camping in their teepees, hunting for buffalo. The Omaha way of life depended on the buffalo. The animals’ meat would feed the tribe through the winter, and their furry coats would become warm blankets and robes. Their skin was turned into moccasins and teepee coverings.

In the past, millions of buffalo had roamed the Nebraska prairie. But those herds were dwindling as white men moved into the Great Plains and killed the buffalo. Sometimes it was for food, but more often it was just for sport. Joseph La Flesche, who was also called “Iron Eye,” was chief of the Omaha tribe. He feared there weren’t many years left when his people would be able to go on their annual summer hunt. What would happen then?

As these problems stood before the Omaha, though, good news spread through the camp. On June 17, Iron Eye’s wife Mary (also known as “One Woman”) gave birth to a baby girl. For a little while Joseph set aside his worries. Right now it was time to greet his new daughter.

Susan La Flesche was born into a big, close family. She already had three older sisters: Susette was eleven, Rosalie was four, and Marguerite was three. (A brother, Louis, had been born in 1848 but had died.)

Joseph also had a second wife, which was common among the Omaha people. From this marriage Susan had a half brother named Francis, who was seven when Susan was born. Her half sister, Lucy, was born the same year as Susan. Another half brother, Carey, came in 1872, the year Susan turned seven.

As soon as she was old enough, Susan was expected to help the family in any way she could. She learned how to plant and harvest crops, and how to dry strips of buffalo meat.

One of her jobs was to carry water from the spring to the house. Susan dreaded that chore! It was a long walk, barefoot over the rough grass, with the sun beating down on her back. And the buckets were heavy!

But there was plenty of time to play, too. Everyone laughed during the dance of the turkeys, when the children imitated the funny way turkeys poked their necks out. Other times the kids stared at one another until someone cracked a smile. Whoever smiled first lost the game—and got water poured over their head. Susan and her sisters played house in teepees that they built, taking care of dolls made from corncobs and dressed in bits of calico fabric. The sisters rode across the Nebraska prairie on stick ponies they made from the tall stalks of sunflowers.

Like all other Omaha children, Susan behaved respectfully around her parents and other adults. She knew it was rude to walk in between a person and the flap of the tent, and she knew not to stare at people—especially strangers! She learned to get up quietly, without drawing attention to herself. Of course she never interrupted when the grown-ups were talking. And from the time Susan was a little girl, the grown-ups were always talking. Big changes were happening on the reservation, and more changes were coming.

Joseph had become chief of the Omaha in 1853. By then, thousands of white people had been moving onto Indian lands. Joseph had seen how the US government had helped these settlers take over the land of other Indian tribes. He knew that the United States wanted the Omaha’s land too. Joseph worried that if the Omaha did not surrender their land voluntarily, the US government might take it by force. The Omaha were a small tribe, and not very powerful. They would not be able to stop the strong US military.

Joseph believed that for his tribe to have a peaceful, productive future, they needed to find a way to live alongside white men—not fight against them. So in 1854 he signed a treaty between the Omaha and the US government. Under the agreement, the Omaha sold the United States millions of acres of land that were their traditional hunting lands. In return, the Omaha got to keep living on a small piece of land, about 300,000 acres, that was nestled on the banks of the Missouri River in northeastern Nebraska. This was now the Omaha reservation.

However, the US government made sure they had a lot of power over the Omaha. The treaty made it clear that the Omaha were to use their reservation land in ways that white men approved of—namely, farming. Although the Omaha were used to raising a few crops, the US government wanted them to take up full-time, large-scale farming, like white men did. According to the treaty, the government didn’t even have to pay the Omaha the money they were owed from the sale of their hunting grounds. Instead, the United States could decide to use the money on programs for the “moral improvement and education” of the Omaha, or for starting farms and buying supplies. In return, the government helped the Omaha set up a mill, for grinding corn and flour, and a blacksmith shop to take care of their equipment. Finally, the US military promised to protect the Omaha from other Indian tribes such as the Sioux, who had been enemies of the Omaha for a long time. To make sure things were done the way the US government wanted, officials established an office on the reservation, called an agency, to take care of things.

Many of the Omaha opposed Joseph’s decision to cooperate with the United States. He had sold almost all the Omaha’s lands. How could they go on their annual hunts, which were so important to the tribe? Joseph sympathized with them, but he was their chief. He insisted that he’d done the right thing.

Joseph started to adopt the ways of white men. In the past the Omaha had lived in earth lodges or teepees. But white men lived in wooden houses with square corners and glass panes in the windows. In 1857, Joseph built a wooden house for his family. It was the first one on the reservation. He planted crops and kept cattle, just like white men. He also joined the Presbyterian Church, which established a mission on the reservation to spread the Christian religion among the Indians. Some Omaha followed Joseph’s lead and built their own wooden houses. But others refused. They mocked what they called the Village of the Make-Believe White Men.

Joseph was proud of his Indian heritage, and he wanted his children to be proud of it too. But he also wanted them to fit into the white man’s world. That meant making some changes. For example, Joseph and Mary gave their oldest daughter a traditional Indian name that meant “Bright Eyes,” but they also gave her an English name, Susette. The rest of the children, including Susan, got only English names. Because Susan and her sisters were daughters of a chief, normally they would have received tattoos to show their status. Not now. Joseph did not want them to look different.

Still, Susan grew up knowing how to speak Omaha as well as English, and understanding the traditions of her people. Many evenings her grandmother would come by the house and tell a story. Susan loved to listen to funny tales of rabbits who played tricks, or to silly explanations for why turkeys have red eyes. Sometimes the stories had a message. The Omaha were patient, cautious people. They did not rush into things. The stories explained that before making a big decision, “the people thought.”2

And so Susan grew up with a foot in two worlds—one Omaha, one white.

Both of them made her think.

Product Details

- Publisher: Aladdin (June 2, 2021)

- Length: 144 pages

- ISBN13: 9781534463301

- Ages: 7 - 10

Browse Related Books

Awards and Honors

- Kansas NEA Reading Circle List Intermediate Title

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Susan La Flesche Picotte Trade Paperback 9781534463301