Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

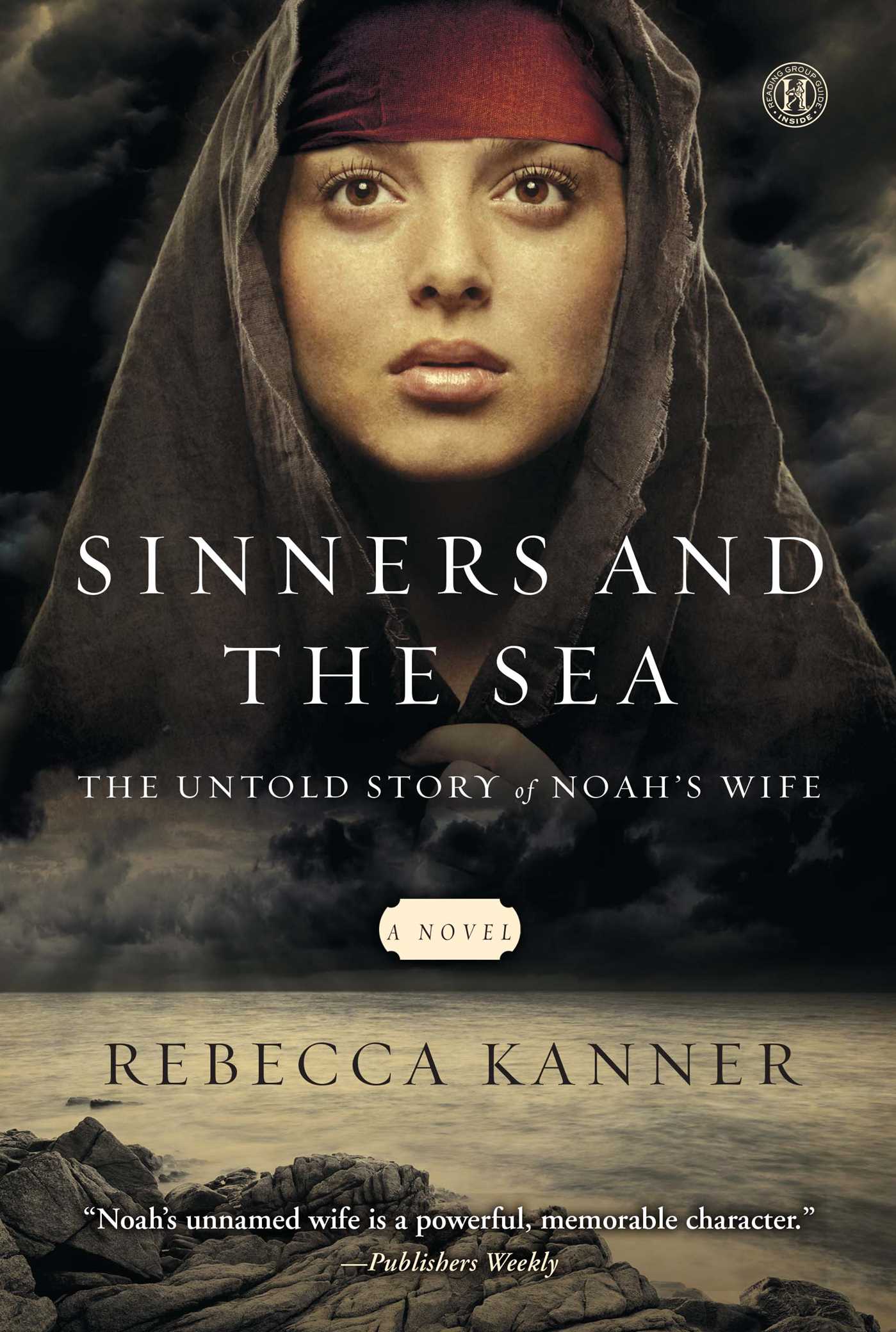

About The Book

The young heroine in Sinners and the Sea is destined for greatness. Known only as “wife” in the Bible and cursed with a birthmark that many think is the brand of a demon, this unnamed woman lives anew through Rebecca Kanner. The author gives this virtuous woman the perfect voice to make one of the Old Testament’s stories come alive like never before.

Desperate to keep her safe, the woman’s father gives her to the righteous Noah, who weds her and takes her to the town of Sorum, a haven for outcasts. Alone in her new life, Noah’s wife gives him three sons. But living in this wicked and perverse town with an aloof husband who speaks more to God than to her takes its toll. She tries to make friends with the violent and dissolute people of Sorum while raising a brood that, despite its pious upbringing, develops some sinful tendencies of its own. While Noah carries out the Lord’s commands, she tries to hide her mark and her shame as she weathers the scorn and taunts of the townspeople.

But these trials are nothing compared to what awaits her after God tells her husband that a flood is coming—and that Noah and his family must build an ark so that they alone can repopulate the world. As the floodwaters draw near, she grows in courage and honor, and when the water finally recedes, she emerges whole, displaying once and for all the indomitable strength of women. Drawing on the biblical narrative and Jewish mythology, Sinners and the Sea is a beautifully written account of the antediluvian world told in cinematic detail.

Excerpt

They say it is the mark of a demon. When I was a child, none took their chances by coming close to me, and certainly no one touched me. It looks as if a large man dipped his palm in wine and pressed it to my forehead above my left eye.

After I was born, the midwife seized the afterbirth and rubbed it over the mark. Then the afterbirth was buried, so that when it decayed, the mark would disappear too. But the mark grew darker. By my second year it had gone from red to purple.

My father tried every known remedy. He anointed it daily with olive oil, rubbed it with a sheep’s hoof, even offered the gods the smallest finger on his left hand to take it away. But the gods did not accept his finger. They dulled the heat of the fire he set to send it up to them so that it only smoked and did not burn.

He had not named me for fear it would be too easy then for people to talk and spread lies, and he was glad of this when the gods would not hear his plea.

There was not another tent within fifty cubits of my father’s. So as not to catch my affliction through their gazes, when people hurried past to catch an errant sheep or child, they looked at me out of the corner of one eye or not at all. Once a man four tents away chased his goat to only a few cubits from my father’s land, then stopped suddenly when he saw me at the cookfire and ran back in the direction he had come.

The goat was never seen again. It was thought that I had changed it into a newborn, the one who was left outside the midwife’s tent one night. Rocks were tied to the newborn’s hands and feet, and he was taken to the Nile.

After this, pregnant women sometimes went to stay with tribesmen in other villages so they would not accidentally see me and have their own child marked in some way. I thought perhaps they also feared that looking at me was a death sentence. My father had told me that my own mother had choked to death a year after I was born. Pregnant women, being the most superstitious of all people, likely thought it was me who sealed her throat around the goat meat.

While I could not tell you what the people of my father’s village looked like up close, the traders were different. They did not fear the mark so greatly. They ventured from the cities along the Nile to haggle with my father for his olives. They brought fruit, nuts, honey, spices, incense, and every kind of grain. They brought flattery, promises, lies, and wine to make my father believe them. He pretended to entertain thoughts of buying large quantities of grain to store in case of a famine, and wool and salted meat in case all the sheep died of the plague that had first fed upon people very young and old, even upon men and women who had been strong only half a moon before their deaths. What he really wanted from them was stories, thinking one might instruct him in how I could be saved.

The traders squatted around our cookfire and let me serve them. But if I accidentally brushed against one as I went around filling their bowls with goat stew and lentils, the man would jump up, curse, and sometimes run to wash himself where I had touched him. One trader even burned his tunic. So I was careful, because I loved to listen to their tales of other places, imagining one of them might be a place where I would not be thought so strange and dangerous.

The traders only spoke of one town with fear: Sorum, Town of Women. It was also known as the Town of Exiles. Though some traders would not venture there, many were their stories of Sorum. It was a town of whores and exiles, people whose foreheads were branded with the X of the banished. Unlike the protective mark that the God of Adam had put upon Cain, the marks on these people were not meant to save them from harm. An X upon your forehead meant that you had committed a crime in one of the cities along the Nile and were no longer welcome. I took a great interest in the stories of Sorum.

An old trader called Arrat the Storyteller told us most of what we knew of Sorum. Whenever he coughed and spat, it meant he wanted to speak. One night the other traders were so raucous, he had to do this over and over again until everyone went silent. Then he rubbed his hand along his beard, rocked forward to his toes, and said, “Sorum. Town of Women.”

One trader narrowed his eyes, another pressed his lips tightly together, and a third pulled his tunic closer around him.

“Now, it is that a woman who is a cross between a girl and a boar guards the entrance. Not to keep men out but, rather, to lure them in. She is uglier than a rotting corpse and smells even worse, yet a man who looks upon her cannot stop his feet from taking him to suckle at her breasts. He will give her all his goods, even the sandals off his own feet. After they have joined together just once, he will pine for her demon’s nectar his whole life. He will bring her fruits and nuts he steals off other men’s trees, oxen and mules he kills other men for. And finally, whatever is left of his soul.

“After she has laid waste to it but before he has fully crossed to the other side, she eats his organs and sucks the marrow from his bones. She does not stop, even though his limbs twitch and he screams for death to take him.

“Then she fashions the bones into necklaces and belts and gives them to the women of the town. Some wear so many bones, they stumble under their weight as though they were overfull with wine. The boar woman herself is decorated so completely with the bones of the men she has eaten that her whole body, except her teats and sex, is covered. Even with this heaviness upon her, she can run faster than a man. And worse, she is stronger than the biggest mule. No one dares cross her.

“No one except a crazed man who rides an ass through town, ancient and unseeing. He is as old as the world itself. So old his beard trails along the ground and gets caught beneath his donkey’s hooves. He yells at the women to repent. He wants to make Sorum upright for his god, the God of Adam.”

This brought laughter.

“His time would be better spent trying to turn a goat into a dove.”

“Or grow an olive grove from a whore—”

“Quiet!” my father commanded, knocking the man’s bowl from his hands. He stood to his full height and gestured toward where I squatted behind the circle of traders, eating my stew after having served theirs.

My father rarely went into a rage, though he had much to be unhappy about. He had a large olive grove and no heir, along with a daughter who could neither inherit the grove nor entice a match. I had heard a man scream at my father only a few days before: “Not even for every olive upon the earth!” The man stomped the ground so hard walking away that he left perfect sandal marks. He was enraged that my father would think him a match for me.

I hurried to pick up the trader’s bowl. “I am sorry,” the trader said, not to me but to my father.

My father said, “Do not think on it any longer.” But he did not buy any of the man’s honey, which surprised me, because eating honey makes a girl more pleasing in nature and shape.

Gods, see how he has lost hope. Please, I beg of you. Help rid me of this mark.

This was my daily plea, the same one I had been whispering each morning upon waking and each night before sleep since first seeing the mark in a pot of water ten years before. But I knew that if the gods had not answered my plea already, they probably never would. I was already nineteen, seven long years past when most girls were taken as wives.

• • •

Then came Mechem the Magical. All the traders had quick tongues but none quicker than his. To a man who labored to breathe, he would sell some wind that he carried in a sack upon his back. He would sell grains of curing sand to the mother of a child with a pus-filled wound. To the sick, he sold the healing droppings of a healthy doe, to the barren, the miracle placenta of a ewe that had birthed three lambs instead of two.

And finally, to my father, for half the olives in his grove, he sold the urine of a great beast. One even more powerful than a demon. The beast had tusks sharp enough to spear spirits, hooves heavy enough to crush them, a trunk long enough to slap them a whole league, and ears big enough to hear them as clearly as a fly buzzing on the beast’s own flank. Mechem promised that, after applying the potion to my forehead, the mark would take only a few days to fade.

“Because of the potion’s great power,” he told my father, “administering it is dangerous. Though I might lose what is left of my life, I will do it for only half the olives that remain.”

My father and Mechem argued back and forth outside the tent, until my father conceded three quarters of his harvest. He lifted the door flap, and he and Mechem came in. Mechem held a small amphora in one hand.

“Our troubles are over,” my father told me. His eyes were full of hope and fear. I knew the fear. He was afraid that the potion would not be able to overcome the mark. He looked expectantly at Mechem.

But Mechem seemed to be waiting. He frowned at my father.

“You will not even know I am here, unless you should need something,” my father assured him.

“The potion will not work with so much flesh vying to be purified.”

“Mine is not in need of purification,” my father said, then quickly looked to make sure his words had not wounded me. “I can stand behind these pots of lentils so the potion is not confused as to which skin to set upon.”

“No, you must leave. I cannot waste what little I have. Unless you possess another olive grove with which to pay me.”

My father’s jaw tightened. He narrowed his eyes at the trader.

“Three men died getting this potion,” Mechem said.

My father came to stand only a few hands’ width from the trader. He was a whole head taller than the little man. “I trust you will do as you have promised,” he said. Then he slipped out the door flap, and I was alone with Mechem.

Mechem looked directly at me. “I do not flinch from demons,” he said. Was this the man the gods had sent to answer my plea that the mark be taken from me? His eyes were glassy and wide-set, like a goat’s. His fingers curled and uncurled as he came to stand beside where I squatted at my loom. He leaned down and whispered, “My own seed will master the demon.” The smell of the wine he had drunk with my father lingered in a cloud between us. I did not have to wonder what he meant.

“But my honor . . .”

“I have two potions, woman. One to remove the mark and one to restore your virtue when I am done.” He pulled another tiny amphora from a pouch tied to his belt and held it in front of my face.

I leaned away from him. “My father is already making me a match,” I lied. “I cannot be tainted.”

“Your father, who did not bother to name you, is now making a match for you?”

“He did not give me a name so that people could not speak of me and spread lies.”

He set the potions down and grabbed my shoulder. His nails dug into my skin. “Silly woman. If you do not have a name, people will give you one: Angels’ Bane, Demon’s Daughter, Demon’s Whore—”

I shook his hand off my shoulder and stood. He pushed up against me, knocking over my loom. “I will take these names out of their mouths when I take the mark from you. You will be a miracle, a woman who overcame a demon. You will have new names: Demon Slayer, Woman of the Gods—”

“I do not care what they call me,” I said, stepping back.

He did not advance. He smiled and said, “You do not know how to lie, woman.”

“I am not as skilled in it as some.”

His nostrils twitched, revealing the stiff black hairs inside. I knew I had erred in angering him. Even though he was a small man, he was still a man, and I was just a woman who no one wanted to take for a wife.

“Please,” I said, “apply the potion only to the mark. All I have is that I am untouched.”

He reached out a finger and pressed his nail against my mark. “But you are touched, for all to see.”

“No one but my father and now you looks closely.”

“People look with their tongues and ears more than their eyes. These very traders whose bowls you fill with your father’s meat and lentils, whose cups you fill with his wine, they do not profit only from their goods. Just as your father has them here so he can hear their tales, so too does he give them one.”

“One is not so many.”

“But it is such a good one, it overshadows all the others.”

“It is nothing that could compare to the story of the boar woman.”

“The demon-woman tale Arrat weaves is riveting. He says your mark changes from red to black and that, after gazing upon it, smoke sometimes comes from his own eyes.” Mechem pretended sadness. “He does not have to clear his throat twice when he goes back along the river. The people there want to know what is in a village so near to their own, a distance a demon could hop in one breath. Do you never worry that men of the nearby villages will come for you?”

“Why would they do so?”

“Who wants to live with a demon so close when there are crops, herds, children, wives, and other property to look after?”

“You are not a good liar either. You go too far.” But I wasn’t certain he exaggerated.

“I do not lie about this.”

My heart beat not only because he wanted to come too close to me but because it suddenly seemed that all the peoples of the world were talking about me in hushed tones.

“Let me help you. Another man has to show the demon he is no match, that he does not own you. It is other men’s fear of you that keeps the demon’s mark upon your brow.” His fingers circled a lock of hair that had come loose from my scarf, and gently ran down the length of it. “Besides, it is a shame to have this mark upon you when you would be such a sweet sight without it.”

He leaned in close again, so that his nose nearly touched mine, and his breath against my lips caused me to stumble backward. The lock of my hair that he still held stretched taut between us.

“The demon is too strong for a man to survive lying with me,” I said, trying to lie more convincingly this time. “He lifts me from my sleeping blanket in the blackest part of night. Things I touch wither and die. If I even look too long at a bird, she will crumple and fall from the sky.”

“I am not a bird.”

“The demon has infected me with his poison so any man who tries to know me will never know me or any other woman again.”

Mechem took hold of my shoulders. He shoved me to the ground.

I could not roll away quickly enough to keep him from falling upon me. The wine on his breath covered a worse odor from his mouth, that of rot, as when a mouse drowns in a pot of nuts or lentils and is not discovered right away. He looked down the length of my body and grasped my breast through my tunic. I struggled to push him off, but my efforts had no effect on him.

He reached his hand lower still and pressed it to my tunic where my legs met. I bit him with all the strength of my fear. I tasted his dry, salty flesh and felt the wiry hair of his eyebrow against my lips. He recoiled, then thrust his hand against my neck. Though the bitter taste of his blood was upon my tongue, I was surprised by the deep gash upon his brow.

His cheeks flared red. “Let me tell you two things, woman. It was not a demon that gave you the mark. It was your own evil mother, and you will do as I say and tell no one, or I will let it be known in this village and all the surrounding ones that the demon has taken every last drop of your soul and uses your body for a vessel. I will show them my forehead, and they will not doubt me.”

“Do not speak false of the dead.”

“Your mother is dead now?” he asked. “Did she finally drink herself yellow and die?”

“She died a year after she bore me.”

He laughed, and his hand loosened on my neck. “And I am the handsomest man in the world! She fled before being branded with the mark of the exile for birthing you.”

“No, I do not believe you.” But I did. I finally understood why my father looked like he had just been hit with a rock whenever I asked about her.

“Even your own mother did not want you,” he said sadly. “Though I am no beauty, and years past the peak of my virility, I am not without an appetite for a woman’s softness. I will do what no other man would dare to and bring you into full womanhood.” He yanked my tunic up over my thighs.

Sunlight streamed into the tent as the door flap was lifted behind Mechem. Before Mechem could turn around to defend himself, my father knocked him off of me unto the ground.

“Fool!” Mechem cried. “I could bring you to ruin with the slightest movement of my tongue. People would flock from leagues in all directions to tear apart your tent, burn your olive grove to the ground, and kill your worthless demon spawn. Now leave us or I will be gone, taking my potion and my tale.”

“We have already agreed upon the price for your potion. I will apply it to my child myself. If the mark disappears within the next four days, then you will have half my harvest.”

“You will have neither my potion nor my silence,” Mechem said. He picked up the amphora with the urine of the great beast and was moving to where he had left the other potion, the one that would restore my virtue after he had taken it, when my father wrapped an arm around him and tried to yank the amphora from his fingers.

“The demon is unleashed!” Mechem yelled loudly toward the door flap. As there were no tents near ours, I doubted anyone heard him. Still, he began screaming as though he were a man dying a horrible death.

My father put a hand over Mechem’s mouth, trying to muffle the old man’s screams. He forced the trader to the ground and slammed his head down with the full force of his weight. There was a great thud, and the screaming stopped.

My father stared down at Mechem. “Wake up,” he demanded. The trader did not acknowledge my father, and his head and limbs moved lifelessly when my father shook him.

My father looked incredulously at the dead man for a few shallow breaths. Then he dropped his head into his hands. “We are doomed,” he said.

Reading Group Guide

Join our mailing list! Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Introduction

Sinners and the Sea recounts the familiar biblical story of Noah and his ark—but this time, the story is told from the perspective of his often forgotten wife. The narrator, who remains nameless until the last page of the novel, struggles to understand her purpose and worth in a world that condemns her because of a prominent birthmark on her forehead. After years of misery and hardship, her father is finally able to marry her off to Noah, a 600-year-old prophet who praises only one God and who has foretold the imminent end of the world. Poignantly written, Sinners and the Sea examines the complexities between right and wrong and calls into question the very idea of righteousness.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. The novel opens with the narrator describing her birthmark: “they say it is the mark of a demon…it looks as if a large man dipped his palm in wine and pressed it to my forehead above my left eye” (10). In what way or ways does this description immediately characterize the narrator and her situation? As a reader, are you immediately sympathetic to the narrator and her plight? Why or why not?

2. Discuss the narrator’s father. Would you describe him as a “good” man? Does he love his daughter, or is he burdened by his daughter’s mark? Do you think his decision to marry her off to Noah is in her best interest? Why or why not?

3. Noah’s extreme old age contributes to the mythical quality of the novel. What are other moments in the novel that you would characterize as mythic? As biblical?

4. Consider the relationship between the narrator and Javan. Would you consider their relationship a friendship? Why or why not? In your opinion, what do the two women have in common? In what ways are they different? Do you think that one woman is more dependent on the other, or do you think the two rely on each other equally?

5. Until the very end of the story, the narrator remains nameless. “It is not because you are unworthy that I have kept you hidden and not given you a name” (38), the narrator’s father assures her, and yet later, when the narrator asks her husband to bestow a name on her he replies: “I already have. Come now, Wife, onwards to Sorum” (50). Discuss the importance of naming in the novel. Why is it significant that the narrator remains nameless? What power does naming have?

6. Is there a hero of this story? If so, which character would you call the hero and why?

7. Is the figure of Noah in the story similar to the prophet in the Bible, or is he different? Do you agree with the narrator’s assessment that Noah cast a “spell of gloom” (104) over the family, or do you think he had other intentions?

8. “But Ham at least would one day have his own family, and then he would make decrees instead of following them. It seemed I never would. I wondered who had more control over her life—one of Javan’s prostitutes, or me” (140). Consider this quote in light of the entire novel. Do the women have as much power as the men in the novel? Do they have more in some cases? Consider the narrator, Javan, and Zilpha in your response.

9. Discuss the narrator’s three sons. Are they a blessing or a burden, or both? Why do you think there is so much competition between the three sons? In your opinion, for whose attention are they vying—Noah’s or the narrator’s?

10. A theme of the novel emerges on page 233 when the narrator says: “If Noah and my sons die when we meet the other ship, who I will be?” Discuss the importance of identity in the novel. Do you think the narrator views herself as anonymous without her family?

11. Can you glean any symbolism from the narrator’s birthmark? In her opinion, the mark brought “shame, humiliation, hatred, and…life” (272). Do you agree with this assessment? How did the mark contribute to the narrator’s “salvation” (272)?

12. Discuss the events that transpired on the ark during the flood. Did the characters change their behavior when they were the only people left on earth, or did they stay the same?

13. Characterize the relationship between the narrator and her three daughters-in-law. Does she favor one over the other? Does she like—or even love—all three? Is there one that she does not seem care for? Did you like one more than the others? Why?

14. Revisit the ending of the story. Did it surprise you that Noah gave his wife the gift of a name?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. Sinners and the Sea lets readers explore a different version of the familiar story of Noah and his ark. Reread the story of Noah from the Book of Genesis 6-9. Compare and contrast the two stories, paying special attention to the character of Noah’s wife. In what ways is she similar to our narrator? In what ways is she different? After reading the two, would you consider Sinners and the Seaa feminist text? Why or why not?

2. Much of the novel is about righteousness and the divide between sinners and saints. But such divides are never clear-cut, and are very often contradictory. For example, the narrator surmises that Noah “liked living among sinners” and that “he did not care for anyone’s righteousness but his own” (149). Discuss the narrator’s position with your book club during a show-and-tell. Define what “righteousness” means to you. Have each member bring in photos, keepsakes, books, or any other objects associated with their definition. Is it easy to define such a complex term? Do you think it is true that often we do not care for anyone’s righteousness but our own?

3. Have a movie night with your book club and rent Evan Almighty (2007). Discuss how the characters in the movie are similar to and different from the characters in the novel. What parallels can you find between the two stories? What are the differences between the book and the film?

4. Following the theme of biblical women, have your book club read The Red Tent (2007) by Anita Diamant. Explore with your group what it might have meant to be a woman living during biblical times. Has society changed its treatment of women? Based on the novels, do you think it is easier for women today than it was then?

A Conversation with Rebecca Kanner

1. This is your debut novel. Describe what this story means to you and why you chose to retell the story of Noah from his unnamed wife’s point of view. What inspired the creation of this story?

As a child I had a storybook about the flood. Noah, his family, and all of the animals walked happily into the ark. The darkness and the rains came. The sea tossed the ark, there were a few pages of rough sailing. Then the sun came out. The giraffes’ heads poked up out of a window. They seemed to be smiling. Everyone piled out of the ark and God put a rainbow in the sky. Noah’s wife didn’t get even one line of dialogue. I wanted to write an adult version of the flood which took into account the hardships of building the ark, the horror of watching hundreds of people die, the fear that God has deserted you, and the guilt and sadness the survivors might have felt. With a woman’s sensitivity, Noah’s wife is able to tell us about all of this, and about her own struggle as the wife of a man tortured by the terrible task he must carry out.

2. Who is your favorite character and why?

I love Javan, the town’s most notorious madam. For the reader she might not be immediately likable. She’s crude and often violent. But she’s also a caring mother who is willing to sacrifice herself for her daughter. There’s something deeply satisfying and life-affirming about finding the good in people, especially when it’s well hidden.

3. Your novel depicts a part of the Bible that we don’t often see; that is, a story told from the point of view of a woman. Was it important to you to present an alternative point of view?

Certainly. I don’t want to look at biblical stories where women don’t get much air time, so to speak, and say, “This is sexist, I wash my hands of it.” I can’t do that. The men and women of the Old Testament were the teachers and friends of my youth. Because the bible often tells huge stories in only a few pages, there’s plenty of room between the lines for us to imagine the lives of biblical women.

4. Would you consider this a feminist text?

The word feminist seems to have gotten a bad rap lately. To me, being a feminist doesn’t mean that I think men and women are the same. It means that women’s voices are as important as men’s. I do consider this a feminist text.

5. Describe the research that went into the making of this novel. Was it a lot or a little?

Initially I was concerned with how much truth there was in the biblical story. I did some research into the plausibility of building such a large ark and taking one or seven pairs of each animal onboard. There was a great flood several thousand years ago. What some scientists will allow is that a smaller ark with all the animals in a local area could have survived the flood. I don’t know what happened, and I’ve come to be okay with that. Dwelling in possibility, being uncertain, is a spiritual position. One of trust and humility and openness. I like that there are things beyond human comprehension. Life is a mystery, and my own life is better if I treat it that way. If I wake up in the morning and say, “Surprise me.”

6. Do you hope to break any stereotypes with this novel?

There are many good, strong women in the bible. I’m thinking specifically of the matriarchs Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah. So I wasn’t concerned with the stereotypes of women someone might take from the bible. But there are current cultural stereotypes that I was hoping to challenge in Sinners and the Sea. When I began the book I didn’t know that Herai was going to be a character. Once she emerged she became very important to me. As a society we tend to value people with certain traits less than others. Herai’s mother, Javan, has insight that the people around her don’t have. With regard to Herai’s “slowness” she says, “What is so good about being quick?”

7. How did you come to be a writer? What is your background and who are your influences?

I became a writer by being shy and loving books. The shyness has faded a bit but the love of books remains. I’ve always been a fan of short stories. In a really good story it feels as though a whole soul has been stuffed into just a few pages. Short stories are haunting as you read them because even at the beginning they’re nearly gone. And because they’re almost always about a sense of loss.

I love the stories of Lorrie Moore. There is a great sense of loss but the writing is so smart and so compelling that the sadness doesn’t overwhelm the story.

Sinners and the Sea is full of loss—the loss of the whole world, the only one Noah and his family have known. But unlike many short stories, I don’t think it’s ultimately a sad story, at least not for most of the survivors. Noah’s wife loses people, loses some innocence, but she also sees that the new world is a gift.

8. Discuss the significance of the birthmark. Is being ‘marked’ symbolic for some greater issue in the novel?

There is some symbolism. I will leave it up to the reader to find it for herself.

9. What would you name as the major theme(s) of this story?

The theme that was most important to me in writing Sinners and the Sea is that the things we dislike about ourselves—our struggles, our mistakes and imperfections, our burdens, our “marks”—can sometimes save us.

10. Who are you reading now? Who is your favorite author?

I’m reading Michael Cunningham’s The Hours. It’s a biographical novel which, as you can imagine, is of interest to me. Who my favorite author is usually depends upon who I’m reading at the time. I just finished the wonderful book, The Round House by Minnesota native Louise Erdrich. The most humbling experience I’ve had in the last couple of years was reading Wolf Hall. Hilary Mantel will go down in history as one of the greatest writers of our time.

11. What is next for you as a writer?

I’m working on a novel about the biblical Queen Esther, an orphan who was taken into the harem of the king of Persia, and went on to become queen. She must stand up to the most powerful advisor in the empire and sway the king if she wants to save her people from genocide. This book is a sort of biblical The Other Boleyn Girl with a touch of Game of Thrones.

Product Details

- Publisher: Howard Books (January 23, 2014)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9781451695250

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“We think we know Noah’s story but he was not alone on the ark; what was the experience of his wife, his family? Rebecca Kanner’s vividly imagined telling recreates the world of the Bible, and asks powerful questions about the story and about ourselves.”

– Rabbi David Wolpe, Sinai Temple in Los Angeles, author of Why Faith Matters

“Rebecca Kanner brings the antediluvian world of giants, prophets, and demons alive, setting her narrative in motion from the first chapter and never letting it rest. She is a writer of great dexterity, performing tricks at a full sprint.”

– Marshall Klimasewiski, author of The Cottagers and Tyrants

“Sinners and the Sea is an excellent example of the traditional Jewish method of Midrash meeting the modern writer’s pen. Kanner does a masterful job of penetrating the depths of the Biblical Flood narrative and weaving in the complicated reality of challenging relationships and longings for personal fulfillment. Her desire to go beyond the traditional midrashic understanding of the lives she explores introduces us to a courageous and insightful young writer whose first book will take its place alongside other exciting modern re-readings of the ancient Biblical text.”

– Rabbi Morris Allen of Beth Jacob Congregation

“Sinners and the Sea is a rare find—a bold and vivid journey into the antediluvian world of Noah. Kanner’s is a fresh, irresistible story about the unnamed woman behind the famous ark-builder. Compelling and masterfully written.”

– Tosca Lee, New York Times bestselling co-author of The Books of Mortals series

"Kanner animates a harsh, almost dystopic world of fallen people struggling to survive. Noah's unnamed wife is a powerful, memorable character."

– Publisher's Weekly

"Kanner successfully undertakes a formidable task retelling a familiar religious story through the eyes of Noah’s wife. The narrative’s well-articulated, evenly balanced, and stimulating—but it’s definitely not the familiar tale that’s so frequently illustrated in children’s books."

– Kirkus Reviews

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Sinners and the Sea Trade Paperback 9781451695250

- Author Photo (jpg): Rebecca Kanner Photograph © Steven Lang(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit