Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

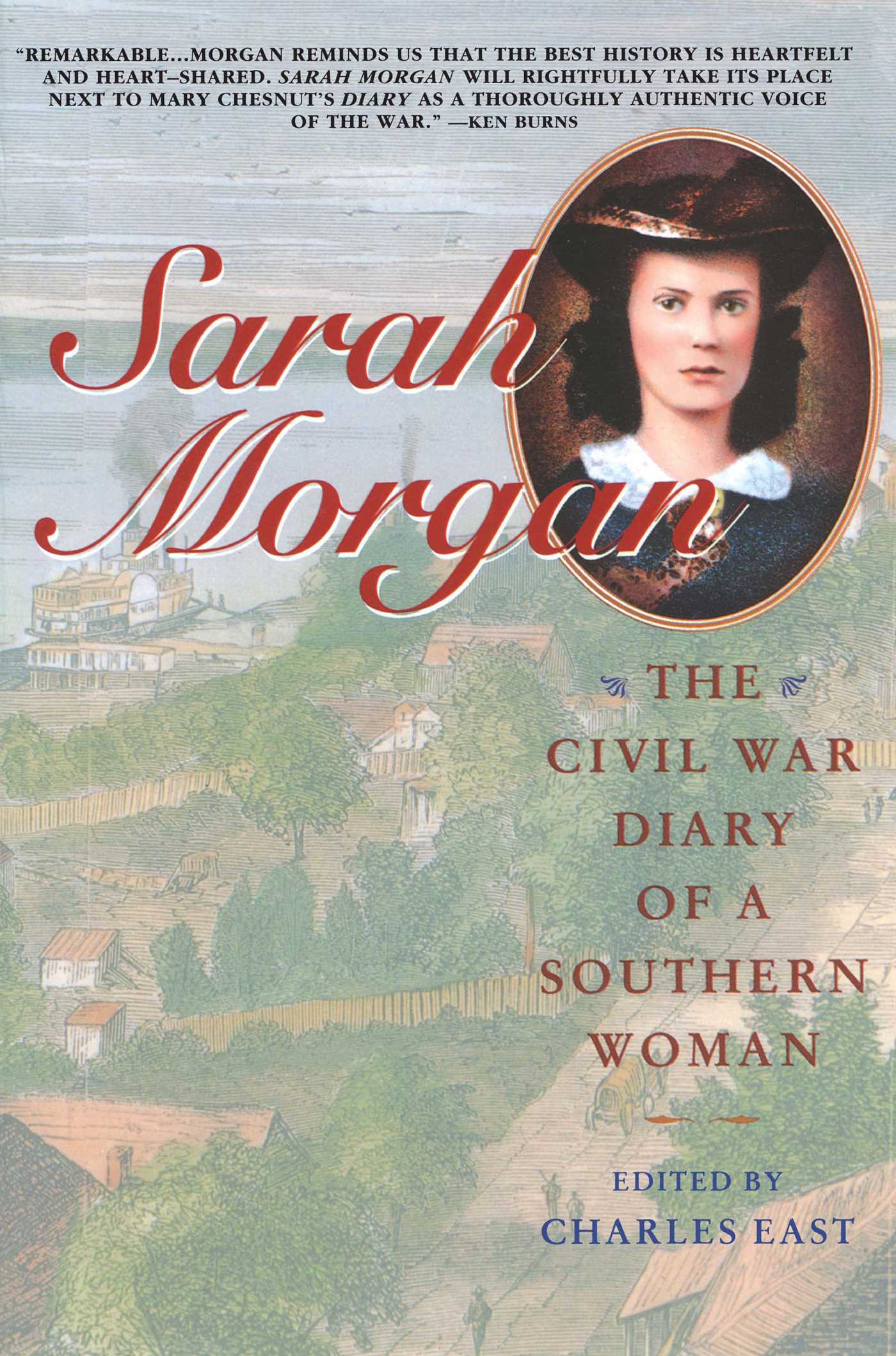

About The Book

Sarah Morgan herself emerges as one of the most memorable nineteenth-century women in fiction or nonfiction, a young woman of intelligence and fortitude, as well as of high spirits and passion, who questioned the society into which she was born and the meaning of the war for ordinary families like her own and for the divided nation as a whole.

Now published in its entirety for the first time, Sarah Morgan's classic account brings the Civil War and the Old South to life with all the freshness and immediacy of great literature.

Excerpt

(This was an old book Brother had in Paris, before I was born. He gave it to me for my 2d Journal, though I call it my First. The other was begun when I was Eleven years old.)

[p. 1] 1862. Jan 10th

B.R. [Baton Rouge]

A new year has opened to me while my thoughts are still wrapped up in the last; Heaven send it may be a happier one than 1861. And yet there were many pleasant days in that year, as well as many bitter ones. Remember the bright sunny days of last winter; the guests at home, the visits abroad; the buggy rides, the walks, the dances every night; the merry, kind voices that came from laughing lips, the bright eyes that then sparkled with pleasure? Is there nothing to remember with gratitude in all that?

What if grief came afterwards; long days and nights of heart breaking grief that only God knows of, [when I was] so heart broken that even God seemed so far off that prayers could not reach him; all the days of my life had been unclouded happiness, without pain or sadness until that awful night when I looked at mother's stony, horror struck face as she lay on the floor with father kneeling over her, and heard her cry out to me with that unnatural voice "Harry is dead! You loved him Sarah!" And my soul seemed to expand in one vast world of agony and then I laughed and said "Father, it is not true! tell her so!" Then as he lifted up his face all tearstained [p. 2] -- my dear old father! -- and said -- "It is true, dear" my heart fairly stopped beating -- and I knew or saw nothing more until I heard his voice saying "My child, for God's sake control yourself!"

It called me back from I know not where; some place that I remember now as being void of everything except awful darkness; and when I saw his face dimly through the veil that seemed wrapped around me, and remembered what he was suffering, with one gasp I conquered something that was dragging me into that dark nothing again, and crept close to mother to help father to hold her. Then, for the first time I knew what grief was. But I had always been so happy until then! "Shall we receive good at the hand of the Lord, and shall we not receive evil also?"

O that dreary night! Presently I found myself in the street. A crowd was gathered at the gate, but I passed through and ran on to where I knew I would find Miriam. I remember putting my arms around her and saying "Miriam, my Harry is dead!" and then we were in the street again, I dont know how -- and presently some one's hand was on my arm and some one said "Hush!" -- I know not why -- but I threw off the hand and ran away; they had no right to hold me; it was my brother that was dead, the one I loved best of all.

People were in the house gathering around mother; they took Miriam too; but I shook them off, for one [p. 3] word or one touch would unnerve me, and I must be brave for father's sake. They said I must go to Lilly and some one took me there where people were standing around her too, and when I saw her come to, only to faint again, I thought she too would die. It was hard to keep from crying then, so every two or three minutes I would run away and hide until I could come back quiet.

That night seemed to last forever. Again I was home; the same scene was there. Mother's dull cry of misery never ceased or varied, Miriam helpless and without self control could do nothing for herself or her. Father had all to do. I tried to help him; I dont know whether I did though. My thoughts were so busy elsewhere. How did he die? the question haunted me where ever I turned, but I dared not ask; I felt what it was. It must have been very late when I asked Mrs Day, and I felt as though it was stamped in red hot iron on my brain; Mr Sparks had killed him -- she need not have told me. I must have known it centuries before, and through all those ages it had been burning in my very soul.

Had he ever lived? It must have been a dream, all those pleasant days, where Harry was mingled with all happy thoughts. Was it years ago, or only a week past that very night that he was laughing at me while I dragged mother around in a dance, that he joined his violin to my guitar, and called on Miriam and Lydia to sing with us? That last supper where we were so [p. 4] happy, where I drew from him stories of London and Paris, and complained that he did not tell me enough, and promised myself that one day, when I should be his little house-keeper, he should tell me all -- was that real? O no! it had never been. "Harry" was a name, a fancy of my own brain -- he had never lived.

And yet in the same breath, I cried "He was so good!" Was! and I did not believe that he had ever existed -- was I said, when the next instant I could not realize that he could possibly be no more! Those were strange thoughts that took possession of me then, and though now it seems to me that I was little short of insane, at the time I fairly hugged myself with the satisfaction of knowing that outwardly at least, I was calm, and that no one would guess what I suffered. I who felt that self control, when there was real anguish, was impossible!

After a while, one by one every one left; Miriam was to stay all night with Lilly, and I was left alone with father and mother. Mother would cry out "What will you do without him, Sarah? you loved each other so! You will miss him, for he loved you best of all!" Poor mother! she forgot her loss in thinking of mine. I believe it was that consciousness of his love for me that was sustaining me through all that. I thought of his life, where we two had been thrown more together than any of the others, and recalling all the past, could thank God that I had never said or thought a harsh word about him.

The day he left home, he had taken [p. 5] off a shirt which mother wanted to use as a pattern for the set she was making him. It was lying at the foot of the bed, where she had been sewing on the others until sunset that evening, with nothing to show it had been worn save the crease in the collar and cuffs. But she cried out when she saw it, and said to take it away. Father wanted to take it; he thought I would be afraid. Afraid of dear, dead Harry who had been so good to me all his life! I could not feel so, and I carried it away my self.

That long night as I lay awake in bed, I held his daguerreotype in my hand, and thought of him lying cold and stiff in the coffin so far away. I could see the gas light shining on his white face, I could see all as though I were present. I thought how fortunate it was that Lydia, Gibbes and I had not gone to Linwood that morning as we intended; how strange it was that when I awoke at five, and heard the rain, I checked my feeling of disappointment with "I'll have to be thankful I cannot go yet" and when I went down to breakfast with a feeling of vague misery that I could not shake off, all laughed at me for my first attack of blues, they said, and declared it was because I did not get off. Father said "This is the first time I ever knew you to give way to a feeling of disappointment; I must say I thought you more reasonable." I felt the reproach, but could only declare that I was not sorry we did not go, I was sure it was for the best, and in return got laughed at again.

Even Lydia wondered at me, and all the morning over at her house with [p. 6] Miriam, I was weighed down with the load I felt on my heart. In going over to dinner, I felt that I must try to be myself again, and commenced singing Harry's "Partant pour la Syrie" to prove my resolution; but I could not finish. At last, while at table I said to Miriam "I will conquer! What o'clock is it?" "Just three." "Good! from this hour, Richard is himself again!" and from that time, I was as gay as I had before been depressed. Laughing still, I went to Mrs Brunot's, and I shall never forget the horror struck face, as she fell back against the wall, looking at me with out a word. I thought she must have heard bad news of Felix, and entered the parlor without staying to ask. The girls met me so singularly, I felt as though I was an unwelcome guest. They were talking of something strange I knew, but the instant I entered all was still.

Three or four gentlemen were there, and all eyed me until I was ill at ease. I tried to talk, but every time I mentioned Harry they seemed unwilling to speak of him, until I really felt piqued about it. Presently, we went to walk in the State House grounds, I with Mr Walsh. I could not help speaking of Harry still. He remarked Gibbes looked very handsome with his hair cut short. I said "That's because he looks like Hal. Hal is the handsomest, as well as the best man God ever made. I know people do not think so, but, Bah! nobody can appreciate him as I do!" He looked so curiously at me, that I was half angry with him; but he said nothing. At last I came home, and taking my guitar sang alone [P. 7] in the parlor until first Lydia, then father and mother came in. Then came that scream from mother, who had gone up for her keys with father; and then remembering how sick he looked as he came in, I thought he must be dying, and ran up too. But I dared not see him die, and ran out in the street calling Gibbes. Lydia caught me, and said "Wait! I'll tell you!" but I could only say Father! and dragged her up stairs with me, while she was trying to tell me, but she never did; mother told it.

O that never ending night! What a relief to see daylight at last, and to be able to get up from the place I had never moved from all night, without thinking of sleep! I dressed in a hurry, and came to this room -- his then -- where all his clothes were lying, as though he would be back in a little while, and folded them and put them away. The brown cap -- the one he said he would save for this winter! -- which he wore until he left, was lying there too. He said he loved it, it had been so serviceable to him; so I took it to keep for him. My task was finished, and the sun was rising on the first of May.

They said Jimmy had come, and running down, I met him in the entry. It was the first time in a year, for he had just come from Annapolis. It was such a sad time to welcome the dear little fellow home; may I never witness such another scene, as his meeting with mother! It was then, for the first time, that we knew how he [Hal] died, fully. Every body knew it, but ourselves, less than an hour after, but we did not know even of his death, until four hours after it occured. Jimmy said he looked [p. 8] so grand lying so still and pale, there was such a holy light shining on his face, and all pain and sorrow had passed away, and Hal's soul was before God, trusting in His mercy. Gone in his brightest days! Gone when all on earth seemed to promise only pleasure, and merited happiness for the rest of his days! Gone, with his heart full of the beauty and goodness of the whole world -- gone to dust and ashes!

O Hal! Was I right in saying when you came home, that you would not be with us long, that Death was shining in your eyes? Mother and Miriam would not believe me, and laughed, but I knew you must go. Those eyes looked too holy to stay here; they did not belong to this world. God sent that light there to show me that he would take you from the harm to come; there is no disappointment in the tomb, Hal; and it was written in the book of Fate that you were not to prosper in this world; your aim was too high, and disappointment would have crushed your soul to the earth. Better be laying in your grave, Hal, with all your noble longings unsatisfied, than to have your heart filled with bitterness as it would have been, for your motto, as I always said when you spoke of future success, was that ominous "Never!" Those glorious eyes, with God's truth sparkling in them, are now dimmed forever, Hal. Yet, not forever; I shall see them at the Last Day; bury me where I may see them again. O please God, let me die as calmly as he. And let Hal be the first to welcome me, and lead me before Thee, in the name of Jesus Christ!

[P. 9] Jan 26th 1862

Three months ago today, how hard it would have been to believe, if any one had fortold what my situation was to be in three short weeks from then! Even as late as the eighth of November, what would have been my' horror if I had known that in six days more, father would be laid by Harry's side! That evening he looked so well and was so cheerful, and felt better than he had been for two weeks; I little thought of what was coming. How well I remember that same day, at our reading club at Mrs Brunot's, I stopped reading to tell the girls of the desk father had that morning given me, and I went on to talk of his care and love, for my comfort and me, until -- I don't know why, unless it was the premonition of his coming death -- I lost all control, and burst out crying, though I tried to laugh it off. At that hour, one week after, I was standing at the head of his grave, looking down at his coffin with dry eyes.

When we came home from reading, we found father with a severe attack of Asthma, but he had it so often, that we thought this too would pass off in a little while; but it was not to be; he never again drew a free breath. At night, he grew so much worse, that Dr Woods was sent for at his request, as Dr Enders could not be found? O how hard I prayed God that he might be relieved! It seemed as though my prayer was answered, and for an hour and a half, he seemed to suffer less. At the end of that time, about nine at night, he told me to go to Lilly, and let Charlie stay with him all night. I kissed him good night as he sat in his arm [p. 10] chair under the chandelier in the parlor, and went away confident that I would find him well in the morning.

I woke at [sic] early the 9th, but dreaded to move for fear that something, which I vaguely felt hovering over me should be true, but Lilly called to me to dress quickly and go home with her, for father had been insensible ever since I had left. At the corner, as we were hurrying here, we met Dr Enders, who laid his hand on Lilly's arm and said "If you go to see your father, you must be prepared for what ever may happen." I waited long enough to hear her ask if he was dying, and his answer "I believe so" and then I was off, and never knew how I reached the parlor.

Father was lying on matresses [sic] on the left of the mantle as I entered, or rather he was sitting up, propped with pillows, for he was too sick to be carried up stairs. His hands were moving as though he were writing, and his eyes, though staring, had not a ray of light in them. Dr Woods, Miriam and mother were supporting him, and someone told me he had not an hour to live. I went to my room then, and asked God to spare him a little while longer; it was dreadful to have him go without a goodbye, our dear father we all loved so. When I came down, I felt he would not die just yet. He was still the same, and until two, we watched for some change. Then he began to expectorate, and Dr Woods told me if he could throw off the phlegm from his lungs, his reason would return.

It was a sad way of keeping Brother's birthday, sitting by what was to be father's death bed. But he grew better towards evening, and they said [p. 11] he was perfectly conscious, and almost out of danger. Mother did not believe them; she said if he was conscious he would want to know what he was doing on the floor in the parlor instead of being in his bed. He seemed to know that he had not full possession of his reason for once when I was sitting by him he asked for his spectacles; I brought them and he said "Where is my paper, dear?" I told him he had not been reading, and he gave me back his spectacles saying "Take them, darling; my mind wanders."

That was Saturday; but Sunday, he was much better, and perfectly himself, as I knew the moment I entered the room, for he put out his hand and said "How is my little daughter today?" We thought him out of danger now, for he talked with every one, and seemed almost well. About twelve, Brother and Jimmy came from New Orleans, for we had telegraphed the day before for them. Jimmy had a violent chill a few moments after he came in, and as I was the least fatigued, I undertook to nurse him. After I got him to lie down on our bed, I had to sit by him the greater part of the time and soothe his head when the fever came on, and hold his hand. He is the most affectionate boy I ever saw. All the time he was sick, he could not rest unless he had his arms around somebody's neck, or somebody's hand in his. I sat by him until night, only looking in the parlor every hour or so to see how father was, and then Miriam and I changed patients; she laid down by Jimmy and went asleep, and I went down to sit up all night with [p. 12] father.

I found him still better, and talking of law business with Brother, so I read until Brother went over to Gibbes' house, where his bed had been prepared. As soon as he had gone, father was seized with Pleurisy, and suffered dreadfully until the next morning. Dr Woods, mother and I sat up with him, the former trying every thing to relieve him. He was very kind to father; as tender with him as though he was a woman; and half the time, would anticipate me when I would get up to put a wet cloth on father's head, and lay it as tenderly on his forehead as though he were his son. I shall always remember him gratefully for that. Father would beg me to go to bed; he was afraid it would make me sick he said; he was always so uneasy about me, my dear father! O father! how your little daughter misses you now! It was almost four when I at last consented to lie down in the dining room but I soon fell asleep, and knew nothing more until sunrise when they told me that father had suffered a great deal after I left.

It seems to be an invariable rule, that whenever I spend a sleepless night, there is a trunk to pack in the morning and this morning I had to pack the children's trunk, for when the Dr pronounced father out of danger, Brother decided to go home, and take the children. I was sorry to see them go, for Charlotte, Nellie and Lavinia had been with us since the 1st of August; but I felt it was for the best. I think they were sorry to leave; they kissed father again and again, and Charlotte actually cried. Brother's good bye was "The Doctor says you will be all right in a day or two; good bye, Pa," as he leaned [p. 13] over him. Father followed him with his eyes to the door, and he never saw him again.

The greater part of the day I was busy with Jimmy who was still unable to leave his bed, but now and then I would steal down and comb father's head with his little comb -- the one I gave him when I was eleven years old, that he ever after used. Better and stronger he still grew, and O how happy I felt. Tuesday he was well enough to sit up in his large chair, and read Sword and Gown through while I combed his silver hair. How little I realized what was so soon to happen! The next day I was sitting by Jimmy rubbing his hands, when Dr Woods came up to see him. He sat there a long while laughing with me, and I went down to see father with him. Charlie was hastily putting up a bedstead where the matresses had laid, to my great surprise, for I had hoped they would have been able to take father upstairs that day, he was so well. Instead of making any remark, I turned to father and told him some joke Dr Woods and I had just been laughing about. He smiled at me, but the gastly [sic], wan look startled me; there was something in his face which had not been there an hour ago.

A sick, deathly sensation crept over me. I heard him whisper -- for he could never talk above a whisper after that Monday -- I heard him whisper to Charlie to help Dr Woods lift him in his bed, and I could hear no more. I ran out of the room with that heart sick feeling. One week or ten days before when I expressed my fear that with his attack of Rheumatism he could not walk up stairs without pain, and had better have a bed brought down, he said to me "My dear, if they [p. 14] ever again make me a bed in the parlor, I shall give myself up for lost. I shall expect never to leave it again." They were putting him in it then; what if his prediction should be realized?

I fought against the idea, and tried to talk cheerfully to Jimmy, and had almost succeeded in persuading myself that I was foolishly uneasy when Miriam passed by and put a piece of paper in my hands. On it was "I do not think there is vitality sufficient to recover from this attack." The words stamped themselves on my memory; they meant that we were soon to be fatherless; Dr Woods' name was signed; he wanted us to be prepared. It was kindly meant, but how cold. They chilled me, those icy words.

I heard Jimmy ask what was the matter, but I could not speak with that choaking [sic] ball in my throat, and that stiff tongue. I felt my way into the little end room, I could not see. And then I knelt and prayed the dear Lord to spare our father, if it might be, if he could be the same that he had always been. But if he was ever to suffer this worse than death again -- if his great noble soul was to be weakened, or deprived of its strength on which we so much relied -- for I remembered how terribly he had suffered -- then, I said, let God take him now, that he may never know this pain again; father would not wish to live without that clear judgement and understanding that has placed him above other men. If God will spare him to us with renewed health, and unimpaired faculties, Well! If not -- God grant us strength to bear it. But I could not bear it patiently; my heart failed me when I thought of father's leaving me here; until then, I had hoped to die first. I gave away in [p. 15] spite of my endeavor to be quiet, so I promised myself that this would be my day, since I could not conquer, but tomorrow should be Miriam's and mother's; I would be calm for their sake. And I kept that promise.

Poor mother! she did not expect father would die, until late in the afternoon, and wonderfully she bore up, never showing what she felt until he lay dying before her. Jimmy guessed what was to happen, and dressed himself and lay down on the sofa, where he could be near father in the parlor, and Miriam took turns in sitting on the bed near him, with me. brushing away the flies and combing his head. It was about four o'clock in the evening. Lilly and I were alone in the room with him, when he whispered something to us that we could not understand. He cast such an imploring look first at one, then the other, but Lilly put her ear to his lips, and said we had not heard. This time he whispered "Have I committed any mortal sin? I believe in the Resurrection and the Life." Then he looked at each again for an answer, but Lilly cried and kissed him. Since he had been taken sick, every one had been coming to inquire about him, and even now they were still sending, and I had to leave the room to answer the same sad thing to each one -- "very low." And then I would have to stay away until I could wipe my eyes and be quiet enough to stand by him.

Sunset came; all without was so quiet and calm; not a breath stirring. I walked up and down the balcony, where I could see him through the open windows. Within, it was more deathly calm than without. Though [p. 16] there were so many there, not a word was spoken, not a hand moved, and the gas, just lighted, was shining on the white coverlid that rose and fell at every painful breath, and father's pale face and silvery hair looked so deathlike that [I thought] my heart would fail me. Several times during the day, I had caught sight of my self in the mirror, and hardly knowing the face that stared so despairingly back at mine, I would whisper "Hush!" to the quivering lips I saw, as though it were a living creature, and would say to the shadow reflected there "It means that tomorrow you will be an orphan," and would vaguely wonder why it trembled so. I felt as sorry for that shadow as though it were living -- and yet, I was not sorry for myself; I tried to forget my own identity.

O how still that room was, with the single sound of that dreadful breathing! It made the silence more intense. Among all those living souls, the noblest there was going: floating out to the Great Beyond. Our hearts sickened and turned cold, his never failed; he knew God was just, and he "Believed in the Resurrection and the Life." It was about eight at night, when he beckoned to Jimmy, and drawing him near, he kissed him repeatedly and said "God bless you my boy! Good-night." Poor little Jimmy burst into tears and ran out of the room. He watched him out, and after waiting awhile, and unable to talk, he put his arms around mother and kissed her good bye, then me, then Miriam. O dear father! can I ever forget that last good bye? It said everything that a last kiss can say; and when I turned [p. 17] away, I felt as though my last and best friend was gone.

How kind Charlie was! All those days he never left his side for more than a moment or two, and only for one or two nights, when Cousin Will or Dr Woods sat up with father did he leave him. No son could have been more devoted. I do not know what would have become of us, without Charlie.

I had determined to sit up all night by father, but half an hour after he had kissed me good bye, they said I must go out while they changed his blisters. I waited with aunt Caro and aunt Adèle in the dining room, but after a while Mr McMain and Charlie said I must go to bed; Lilly was lonesome up stairs, and the Doctors found father much better, they would call me if he needed me. I do not know how it happened, but presently I found myself lying on the bed near Lilly, and slept for some time, when Miriam woke me to say father was still better, and I must take my clothes off and go back to bed. I had not the energy to resist, and did as I was told, though every half hour I would wake up, to hear Charlie tell Lilly how father was, and directly fall asleep again. It was always "His pulse has gained" "He is stronger" "Dr Enders finds him much better," until I persuaded myself that he would get well. I kept repeating "O live father! live for your children!" and would fall asleep praying that father might be spared.

The last thing I heard, was that he was still better; it was then half past four. I fell into a heavy sleep, and did not wake until I felt someone trying to raise me up, and kissing me, to wake me. It must have been a few moments [p. 18] after seven then. I half way opened my eyes, and saw it was Tiche, but had not the energy to say anything though I had not seen her for several weeks, she having come up from New Orleans while I was asleep. I heard her say "Run to Master," and then she was gone.

Half way dreaming, I got up, and slowly put on my shoes and stockings. Then I deliberately commenced to comb my hair, but just then, Margret came in and said "Never mind your hair; Master is dying; run!" In another instant, I was standing by him. I remember to have heard them carry Lilly out of the room, while she was crying; but I saw nothing until I reached his bed. Someone was holding mother, as she stood at the head, wringing her hands and afraid of touching him. Poor mother! how she was crying! Miriam had thrown herself by his side, on the other side of the bed, with her face buried in one of his pillows sobbing aloud, but no one was touching him. So I went to him as he lay on the edge of the bed, and put my left hand in his, while I laid my right on his fore head. The hand of death would not have been colder than mine; but I remembered my promise "To day is mine, tomorrow, Miriam's and mother's," and did not shed a tear.

Father lay motionless, save for that deep drawn breath, each of which seemed to be the last, with his eyes perfectly blue and unclouded fixed on the parlor door, as though waiting for some one to enter. Only four times can I distinctly remember having seen him breathe after I came in the room. What a long, long interval there was between [p. 19] each! It may have been only a few moments that I stood there, but to me it seemed hours. Presently I bent over him to see him breathe again, but mother cried "Shut his eyes!" and closed them with her own hands. I kissed him as he lay so motionless, and turned away, for I knew father was dead. Jimmy was crying aloud in a chair at the foot of the bed, but I dared not go to him; one word, one touch would have unnerved me, and I had my promise to keep. So I went to my room, and hurried on my clothes, for all this while I had been standing in my nightgown.

I looked at the watch as I went out -- quarter past seven, it said. When I came back, every one had disappeared, except aunt Adèle who was brushing away the flies. I took her place, and she left me alone with dead father. It seemed impossible that he should be dead, he looked so warm and lifelike, and then I held my breath to hear him breathe again. From that hour, the idea that he would presently come to, never forsook me until I saw his coffin lid screwed. People wondered at my self control, but I could never have kept my promise so faithfully, if it had not been for that wild thought.

I dont know how long I sat there alone, but presently the men came to dress him, and Charlie took me away. The slippers I worked for him his last birthday were at the foot of the bed, where he had them put when he took them off the day before; the little comb was lying on his pillow, so I took them away with me. [p. 20] When I had brought his grave clothes, and the men had finished, Miriam and I sat down on each side of him, and remained there except for a moment or so at a time, all day. People came in in crowds, but I wanted them to be quiet; I felt I would give away if I spoke.

About ten, it must have been, Lydia came; she knew he was very sick, and the crape at the door told her the rest. She held on to me as she looked at his dead face; they all seemed to think poor weak me the strongest. Father had been so kind and tender to her; no wonder she cried so bitterly! I could not stand it; but I remembered what father said when Hal died -- that I had more fortitude than any woman he had ever seen -- and I determined to make his words come true. But it was a relief when Lydia went up to mother; I could be quiet then.

People might come and go; I neither saw or cared for them; my hand was on father's head, I was watching for the eyes to open, I was thinking of those away. Poor Sis! this will break her heart! California is such a long way off, and even now she does not know what has fallen on our home! George was at Norfolk; he left New Orleans the day before Harry died. Gibbes was at Centreville; Brother should have been there at daylight, and father had died waiting for him, and though the day was wearing on he had not come.

Sunset came, then the early twilight, and only Mattie was left with us. I still kept my place with my hand on his forehead, watching. I could see the moon [p. 21] shining on the white fence over the way, and the blue sky through the open windows. Then the gas was lighted, and shone just as it did last night full on his quiet face and silver hair. But last night those lips called me and kissed me, and to night -- O it was so sad!

Then those who were to watch, came in, but I did not look at them; I heard them while I was watching. Later, Charlie put his arm around me, and carried me in the dining room to get my supper; it was hard to eat, but I tried to please him, and when I wanted to go back and wait, he would not let me. Then I promised, if he would let me kiss father good night, I would do whatever he pleased. So I kissed him for Sis too, and went back as I said I would, and Charlie made me go to bed with Lilly. I kept quiet; I hardly dared breathe for fear I should cry; but I grew so cold and numb, I thought my blood was frozen. We were lying in father's bed, and directly below, he was lying so stiff and cold! I could see him as though I were standing by him, where ever I turned even with my eyes shut I could still see him; and that awful hush seemed to pervade the whole world. Then a step broke the stillness, and I knew Brother had come; he could not have known it until he reached the door, and he was standing by our dead father at that moment. I grew colder and colder, until I crept closer to Lilly, and I knew that at one touch I would give away, for I cried my self asleep in Lilly's arms.

Then the next morning before sunrise, I was sitting [p. 22] by father again, looking at his grand head. It looked so magnificent, there was some thing so majestic in the form, that I could not cover it up. Brother came and stood by me; he too was trying to control himself; but I knew all he was suffering, by what I suffered myself. Presently came the men with an iron coffin, and set it down almost at my feet, with a dull, hollow clang, that went to my very heart; and they said Miriam and I must go out; but we would not, and stayed by, and saw him put in it. When they brought the lid, we kissed him good bye -- poor Sis! I kissed him for her too -- and Brother cried, but did not touch him; and even I had to turn to the window, for the tears would come. And we watched them cement the iron lid, and screw it down, and then I took my old place at his head, and held the handle nearest me, though I could no longer see his dear face again.

I took no notice of time, but I must have been there a long while, when I was roused by footsteps, and saw two or three strange faces looking at me. I knew it must be ten, so I put on my bonnet and cloak, and came back to him, and layed my hand on his coffin. Some one made me go to the other side of the room, I dont know who, for when I tried to see, there was only an indistinct sea of faces before me, and I did not even know whether I had ever seen them before. I knew nothing except that father was lying dead in that coffin before me.

When [p. 23] Mr Gierlow said "I am the resurrection and the Life" I looked up, and saw him standing by the side of the coffin, and only Brother at the foot, who put out his hand for me. I got up, and groped my way towards him, for all save those three in the centre was indistinct to me. and he caught me and held me tight while Mr Gierlow read the service, until the prayers, when I knelt alone by father, with my face on his cold coffin. Presently there was a deep hush, and then, looking up from the chair brother had placed me in, I saw them preparing to carry father away. Then Brother put my hand on his arm, and slowly made his way through a crowd that suffocated me, as far as the front door, and there Gen Carter took me away from him and passed through a still greater crowd, until he put me in the carriage with Miriam and Lydia. and Howell got in with me, and we slowly drove off.

Then came the dreary drive to the graveyard, following in the very steps of the horses that were carrying father away from us; and then, we stopped at the gate, and Howell gave me his arm, and took me to the enclosure where Hal was burried [sic], and stood with me at the head of an open grave, where I knew father was to be put. Brother, Lydia, and Miriam stood at the side, and then they brought father, and lowered him into his last home. I tried so hard to keep my promise, that God gave me [p. 24] the strength, and I watched him down in his grave without a tear, only holding tighter still to Howell to save myself from falling. "Earth to earth, dust to dust, ashes to ashes," the earth raffled on the coffin lid, the last prayer was said, I looked for the last time at what held all that remained of our dear father, and Howell was once more putting me in the carriage, and I was going home.

Home! What a dreary, desolate place it was! How forsaken every thing looked! There was such a strange echo in the deserted rooms, such a forlorn look in every place! All that made our home happy, or secured it to us, was gone; a sad life lay before us. My heart failed me when I remembered what a home we had lost, but I could thank God that I had loved and valued it while I had it, for few have loved home as I. Sis, Hal, and I, it is all we lived for. How it would have pained Hal to see that day! I was thankful he had gone before. It would have broken his heart if any of us had died. And O Hal my darling, how I miss you now! How I long for you, wait for you, pray for you, and you never come! Do you no longer love your little sister? Father is with him now; both lying so close together, yet so far apart; side by side, and they speak not, though they once loved one another so much!

Once more alone, and all control was thrown to the wind; it would have killed me to be calm then. And after [p. 25] dinner, when Brother made Miriam and me sit on his lap, when the others had gone, and talked so kindly to us, when he laid his head on the table and cried until his whole frame trembled, at the mere mention of father's name, I felt marble again and could pity and soothe him as though he were the weak woman, I the strong man. Where did I get that strength?

He talked so nobly and kindly to us, and said he would be our father, and love us and care for us as the dear dead one did, that we no longer felt hopeless and forsaken. Are kind words recompensed in Heaven? Then surely God will bless Brother for the words he spoke that evening. And it was decided then, that until George could come from the wars and take care of us, Lilly and Charlie would stay here with us, until something else could be done. After all, we would not be utterly helpless; with God in heaven, our brothers on earth, should we not be thankful? And this is the simple story of how my poor mother was made a widow, and we were left orphans on that sad fourteenth of November, 1861.

Copyright © 1991 by the University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia 30602

Product Details

- Publisher: Touchstone (February 5, 1993)

- Length: 672 pages

- ISBN13: 9780671785031

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

Ken Burns Remarkable...Morgan reminds us that the best history is heartfelt and heart-shared. Sarah Morgan will rightfully take its place next to Mary Chesnut's Diary as a thoroughly authentic voice of the war.

The Greenwood, S.C., Index-Journal Refreshing....A real-life Scarlett O'Hara.

Lexington Herald-Leader Stands virtually alone in bringing the Confederate homefront to life...Irresistible.

Christian Science Monitor Sarah Morgon's diary is not only a valuable historical document. It is also a fascinating story of people, places, and events -- told by a wonderfully talented writer.

Huntsville Times You don't have to be a Civil war buff to enjoy Sarah's story. It's a fascinating tale of life in an extraordinary time and place....By the time the reader reaches the final pages it's tough to leave.

Richmond News Leader Sarah Morgan's diary will henceforth be linked in value with the diary of Mary B. Chesnut....Miss Morgan's personal feelings and intimate thoughts eclipse even [Chesnut's]....Always, throughout this work, are the inner thoughts, dreams, and conflicts with reality that daily consumed a young lady who, in so many respects, was above the intellect of her times....It is deserving of all the praise, and of all the use, that it will receive.

Drew Gilpin Faust Annenberg Professor of History, University of Pennsylvania The diary of Sarah Morgan, at last available in its complete form, is both a delightful read and an invaluable source for southern, women's, and Civil War history.

The Orlando Sentinel A remarkable diary....As she writes of her hopes, fears, and sadness, Sarah Morgan emerges as an extraordinary person forced to grow up fast in the crucible of the Civil War.

Library Journal Morgan's diary should rank alongside Mary Chesnut's famous wartime journal as one of the most important personal records of the Civil War. Highly recommended.

The Charleston Post and Courier Adds immeasurably to an accurate portrait of life on the Confederate homefront....Intelligent, sensitive, and well educated, [Sarah Morgan] could put into words what her eyes saw and her heart felt....An extraordinary account of how one family responded to the war and suffered the consequences of its decision.

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Sarah Morgan Trade Paperback 9780671785031