Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

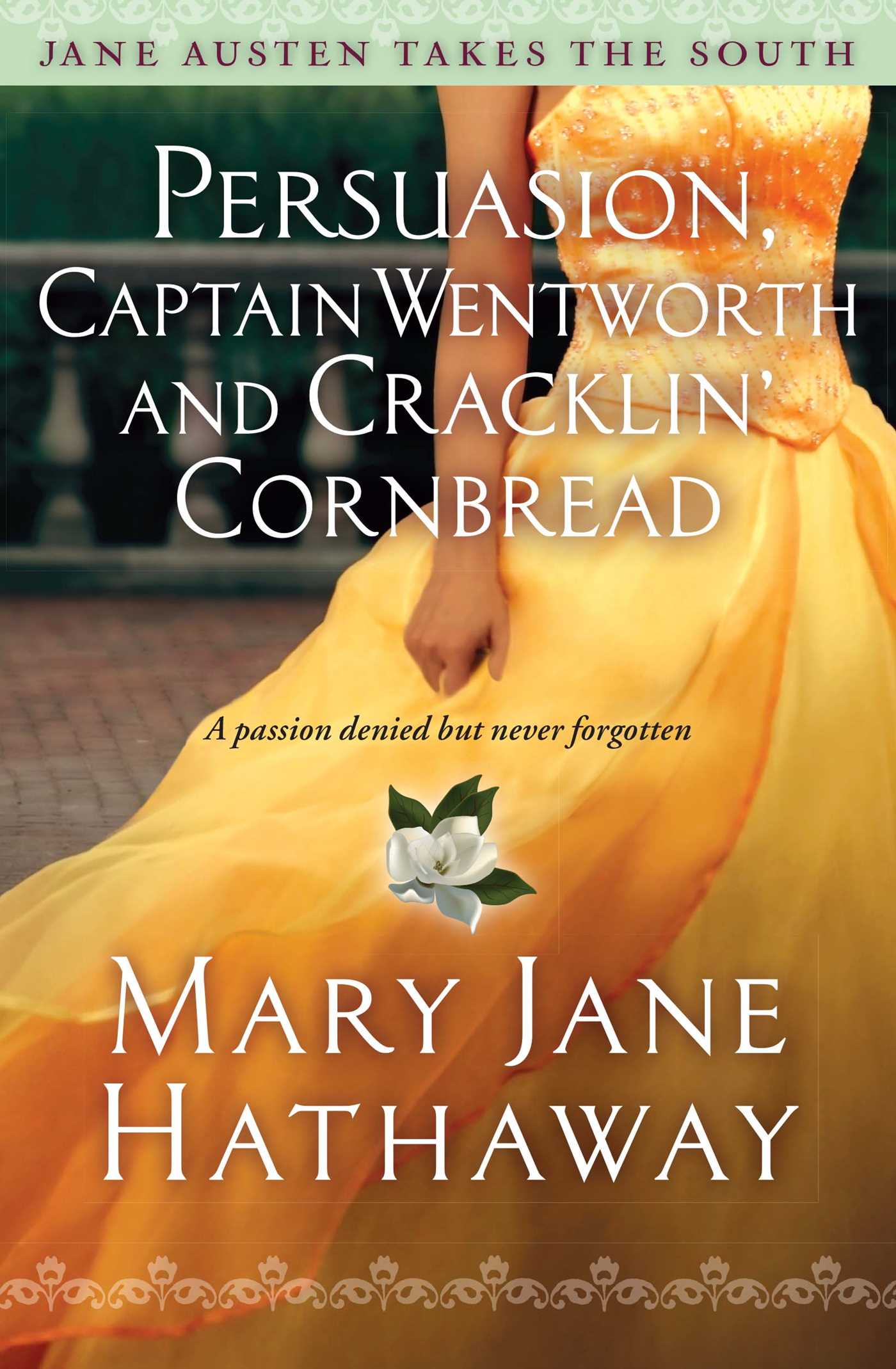

Persuasion, Captain Wentworth and Cracklin' Cornbread

Book #3 of Jane Austen Takes the South

Table of Contents

About The Book

A lively Southern retelling of Jane Austen’s Persuasion, featuring Lucy Crawford, who is thrown back into the path of her first love while on a quest to save her beloved family home.

Lucy Crawford is part of a wealthy, well-respected Southern family with a long local history. But since Lucy’s mother passed away, the family home, a gorgeous antebellum mansion, has fallen into disrepair and the depth of her father’s debts is only starting to be understood. Selling the family home may be the only option—until her Aunt Olympia floats the idea of using Crawford house to hold the local free medical clinic, which has just lost its space. As if turning the plantation home into a clinic isn’t bad enough, Lucy is shocked and dismayed to see that the doctor who will be manning the clinic is none other than Jeremiah Chevy—her first love.

Lucy and Jeremiah were high school sweethearts, but Jeremiah was from the wrong side of the tracks. His family was redneck and proud, and Lucy was persuaded to dump him. He eventually left town on a scholarship, and now, ten years later, he’s returned as part of the rural physician program. And suddenly, their paths cross once again. While Lucy’s family still sees Jeremiah as trash, she sees something else in him—as do several of the other eligible ladies in town. Will he be able to forgive the past? Can she be persuaded to give love a chance this time around?

Lucy Crawford is part of a wealthy, well-respected Southern family with a long local history. But since Lucy’s mother passed away, the family home, a gorgeous antebellum mansion, has fallen into disrepair and the depth of her father’s debts is only starting to be understood. Selling the family home may be the only option—until her Aunt Olympia floats the idea of using Crawford house to hold the local free medical clinic, which has just lost its space. As if turning the plantation home into a clinic isn’t bad enough, Lucy is shocked and dismayed to see that the doctor who will be manning the clinic is none other than Jeremiah Chevy—her first love.

Lucy and Jeremiah were high school sweethearts, but Jeremiah was from the wrong side of the tracks. His family was redneck and proud, and Lucy was persuaded to dump him. He eventually left town on a scholarship, and now, ten years later, he’s returned as part of the rural physician program. And suddenly, their paths cross once again. While Lucy’s family still sees Jeremiah as trash, she sees something else in him—as do several of the other eligible ladies in town. Will he be able to forgive the past? Can she be persuaded to give love a chance this time around?

Excerpt

Persuasion, Captain Wentworth and Cracklin' Cornbread

No: the years which had destroyed her youth and bloom had only given him a more glowing, manly, open look, in no respect lessening his personal advantages. She had seen the same Frederick Wentworth.

—ANNE ELLIOT

Chapter One

“?This is an effort to collect a debt. Any information obtained will be used for that purpose.”

Lucy Crawford leaned her forehead against the wall and closed her eyes. The mechanical voice droned on, rattling through an 800 number and requesting a call back. The time stamp was an hour ago.

There was a brief pause and the next message began: “This call is for William Crawford. I am a debt collector and this is an effort to collect a debt. Any information—”

Lucy reached out and punched the skip button. The message machine flashed three more calls in the queue. She didn’t know if she could listen to them all at one time. It was too depressing, like watching the recap, over and over, of the Bulldogs falling to Alabama by thirty points. Except that there was always next year for her favorite football team, and there wasn’t any end in sight to her daddy’s financial issues.

Skip. Skip. Skip. Maybe all the calls were from the same creditor, but probably not. Lucy heaved herself upright and trudged into the foyer. She might as well get the mail now while she was already feeling low. The black-and-white tile expanse of the entrance area gleamed dully in the summer light shining through the leaded panes of the double doors. In all of her twenty-eight years she had never seen them so scuffed. Old Zeke polished the floors of every room in the house once a week and always spent extra time on the entrance. He was proud of his job and being part of keeping up the historic Crawford House. Or at least he had been, until Lucy had fired him.

She paused in front of the side table, where a five-inch stack of bills waited neatly. The conversation with Zeke flashed through her mind and she felt the unfamiliar burn of tears. She wasn’t a crier. When she’d sat Zeke down, she had done well, speaking clearly and confidently until he had bowed his head. The defeat in his posture was like a stab of hot iron in her heart. Zeke had always seemed larger than his five-foot-five frame, probably because Lucy remembered being very little, pulling on his pant leg and looking far, far up at the Crawford House handyman. He was like family, and she was telling him he wasn’t going to be part of their daily lives any longer.

Then he had glanced up, black eyes still bright despite his seventy-five years. “Miss Lucy, I know’d this time be coming. I’s not as strong as I once was.”

She had wanted to drop to her knees, wrap her arms around his fragile shoulders and cry like a little girl. She’d wanted to cry like the time she’d lost her dolly down the irrigation pipe in the back pasture, before Zeke had retrieved it for her. Like the time she’d broken her heart into tiny pieces and he sat beside her, patting her shoulder and whispering, “There, there,” until she fell asleep, soggy and exhausted.

But she hadn’t. Lucy had explained, again, about the debts and the home equity loan and the repairs they couldn’t afford. No matter what she’d said about bills and bankruptcy and foreclosure, old Zeke hadn’t quite seemed convinced. The memory of it was so strong she felt chilled, even standing in the stifling air of the foyer. Lucy reached out and grabbed up the pile of envelopes, not even bothering to glance at the addresses. They wouldn’t be able to pay them, or any new ones that would have come in.

“Honey, is that you?” Her daddy’s rich baritone echoed through the large entrance hall. Seconds later he appeared around the corner, dressed in a perfectly pressed pair of yellow-and-green-plaid golf pants, Ralph Lauren polo shirt casually unbuttoned at the neck. Willy Crawford’s close-cropped hair was still black, except for a bit of gray at each temple, and for a man of sixty, he was still lean and fit. “I’m headed to the club for a quick round with Theon James.”

Lucy winced inside. Theon James excelled in three things: golf, business and goading her daddy into spending money to keep up his reputation as the richest man in town. She suspected Theon was playing a game, enjoying how easy it was to convince Willy Crawford that it was time to get a newer car or take a monthlong vacation to St. Simons Island.

“Will you be home for lunch? I have a casserole in the oven I think you’d really like, Daddy.”

He cocked an eyebrow. “Does it have any meat in it?”

She was tempted to lie. Really, he acted as if vegetarian cooking were poison. “No, but the eggplant tastes just like—”

“Nah.” He pulled on a matching green-and-yellow-plaid golfer’s cap and shouldered his bag. “You know I don’t like that sort of thing. Put some ham in it next time. And don’t say I always need my meat, because I eat some of that vegetarian food, too. Your mama was a great cook. Her beignets were so light and fluffy, fried just right, a good bit of powdered sugar on top. . . .” He paused, a small smile on his face. Lucy knew just what he felt. Sweet memories were all they had left of her mama.

“Before you go,” she started to say, holding out the mail. ?He cut her off. “No time now, sugar. Theon’s already there.” Her daddy leaned in and gave her a quick kiss on the head, leaving a whiff of Old Spice and cigars.

“It’s just I thought you were fixin’ to sort through some of these on Sunday after church, but you went out to lunch. We need to see if there are a few we could pay off right away. It would save a lot on interest in the long run and . . .”

He wasn’t listening to her. Bending over his golf bag, he rummaged inside. “When I get back, I’ll take care of it. And there’s no we about payin’ these bills. I’ve got the money, just need to cash out a few old savings accounts and I’ll be settled up with those people.”

Lucy almost sighed out loud. Those people. Her daddy always drew a thick black line between their family and the rest of the world. If she tried to suggest that they were close to bankruptcy, he would point out how the Crawfords had owned the finest home in Brice’s Crossroads, Mississippi, since right after the Civil War had ended, or how his great-granddaddy had founded the area’s first African-American business league, or how the Crawfords had attended Harvard before the Roosevelts. The Crawfords were good stock. They were on the boards of hospitals, joined exclusive clubs, were admired by everyone. They didn’t have financial issues, and they certainly didn’t worry out loud if they did.

“Some of these are probably Paulette’s,” Lucy said. “You’ve got to get those credit cards from her. She’s got closets full of designer clothes and she just buys more.”

“Your sister is a fine-lookin’ woman in search of a husband. I won’t be interfering with that.” He winked at her.

“But Janessa managed to get a husband without spending sprees in Atlanta.” Lucy crossed her arms over her chest. Her middle sister had many faults, but being a fashionista wasn’t one of them.

“You leave Paulette be. She’s not like you. She’s still young and hasn’t given up on men. I don’t mind her spending a bit to make herself look presentable. It’s part of keeping up appearances. She certainly doesn’t want to live in her daddy’s house the rest of her days.” His voice was light, but there was a warning in his eyes.

Did he think she’d given up on men? She swallowed past the hurt of his words and said, “Alrighty, as soon as you get back, let’s go over these bills together. Mama’s not here. You need to keep track of these things.”

“Don’t be disrespectful.” His face was stiff with anger. “I didn’t raise you like that.”

Lucy dropped her gaze to the floor. When she was little, her daddy had heard her mouth off to her mama. He hadn’t used the switch on her, the way she’d thought he would. He’d sat her on his knee and explained he could forgive a lot of sins, but he could never love a stubborn, strong-willed girl. She’d apologized to her mama and tried her very best to be a good girl ever since. She was a grown woman now, but Lucy still couldn’t seem to balance on that fence between gentle coaxing and shrewish nagging.

“I didn’t mean to offend, Daddy.”

The door was already closing on the end of her sentence, and Lucy listened to him cross the wide, wooden porch. His footsteps faded with each step toward his shiny red Miata. She sagged against the side table and resisted the urge to throw the whole stack of letters against the door. He wouldn’t listen. She had done everything possible to keep the bank from foreclosing on the house, but it was only a matter of time before they lost everything. Her mama had been so good at managing the household finances. Maybe too good. Her daddy had been happy to turn it all over to her and focus on his golf game. He was the face of Crawford Investments, but her mama had been the brains. When she passed, he’d just pretended that nothing had changed, creating chaos at home and disaster for the business.

Just the thought of her mama gave Lucy a sharp pain, even though it had been close to nine years now she’d been gone. One early morning she’d collapsed in the kitchen and Lucy’s life had changed forever.

Lucy breathed a prayer of thanksgiving for the time they’d had together, all the way through her teens. She used to love sitting in the bright-blue kitchen and watching her mama cook. Their housekeeper, Mrs. Hardy, made perfectly fine meals, but her mama wasn’t happy if she didn’t mix up a batch of gumbo or hush puppies once in a while. Straight from Cane River, she spoke with the lyrical accent of a native Creole speaker and had eyes the color of Kentucky bluegrass. She liked to sing, all the time, and it was like having a radio you could never turn off. Gospel hymns, blues, low-country ballads. The house was so quiet without her. Lucy had the dark eyes and skin of her daddy, but her curves and throaty laugh were all her mama’s doing.

She still had the curves, but it had been months since she’d heard herself laugh.

A rap at the door sounded like a gunshot in the quiet foyer. Lucy hesitated, wondering if bill collectors ever came to the door in their “attempts to collect a debt.” Peeking through the beveled glass, she let out a breath. When trouble comes, family arrives close behind, for better or for worse.

“Auntie,” she said, swinging the door wide.

Aunt Olympia held out both hands and stuck out her lower lip. “Oh, honey, come here.” She gripped Lucy’s hands and hauled herself over the threshold like a shipwreck victim grabbing hold of a life raft.

“You got my message,” Lucy said into her aunt’s elaborately braided updo. Lucy was being squeezed and rocked from side to side, and her words sounded as if she were running.

“Yes, bless your heart. And I’ve been busy solving your problems,” Aunt Olympia said. Letting go of Lucy, she shut the door behind her and started toward the kitchen. “Come let me tell you all about it over a little sweet tea.”

Lucy knew better than to laugh. There was no way Aunt Olympia could have solved anything in the hours since Lucy had called, giving the dire news of the impending foreclosure. Instead, Lucy trailed along behind her, wondering how such a tiny woman could exude such force. Where Olympia went, everyone followed.

“Aren’t you supposed to be at the museum today?” her aunt called over one shoulder. Of course she would have noticed Lucy’s jeans-and-T-shirt ensemble right away. Her aunt didn’t believe in casual clothes. Her neon-green track suit said JUICY on the rear, and her earrings bounced with every movement. She was all flash, all the time.

“They’re closed for maintenance, and it’s an interpretive center, not a museum.” Lucy didn’t want to talk about her job. Aunt Olympia would say Lucy should have a better position, maybe something with a fancy title and a yearly bonus.

“Which means what? Cleaning?” Aunt Olympia moved around the cheery kitchen, reaching into the fridge for the pitcher of tea.

Lucy dropped into a chair. “Yes. Cleaning.” Maintenance made it sound as if the center might get a new roof or any of the other desperately needed repairs. But upgrading access to a Civil War battlefield site wasn’t high on the list of popular causes in Tupelo.

“I don’t know why you work over there. You probably are only gettin’ the people who wander through from the Elvis museum.”

Lucy said nothing. The sad fact was, if Elvis had been born in Brice’s Crossroads, they’d have an event center with a full kitchen, green rooms and a theater—not to mention a chapel and a gift shop with its own apparel line. As it was, they had to make do with folding chairs, a microwave and a yearly budget that wouldn’t cover Graceland’s electric bill.

“Hun, you need to find yourself a better job. Iola is working on the top floor of a smoked-glass high-rise in Atlanta. She wears the prettiest outfits and has a whole closet for her shoes. She says—”

“I know,” Lucy interrupted, unable to stand hearing one more time about her cousin’s happiness at being a secretary for a group of slick lawyers in pin-striped suits. “I know,” she said more slowly. “But working at the center is perfect for me, Auntie. I love this area, these people. If I could have majored in the history of Tupelo, Mississippi, I would have. Being a curator doesn’t come with fame or glory, but it makes me happy.”

Aunt Olympia’s frown softened into a sigh. “You deserve a little happiness, that’s for sure.”

Lucy wondered for a moment if she meant because of the way her mama had passed away so suddenly, or if Olympia was talking about another time, long before. An image of a laughing, blond-haired boy flashed through her mind and she shoved it away. Her present was bad enough without wallowing in the past.

Her aunt glanced in the oven. “Is that lasagna? You know your daddy doesn’t like ethnic dishes.”

“It’s baked ziti, and he’s already taken a pass.”

“Oh, honey, you need to learn how to cook. You’re never going to catch a man with that kind of food.” Aunt Olympia shook her head, as if knowing the perfect fried chicken recipe would solve Lucy’s single status.

She didn’t want the conversation to veer off into marriage talk. “What sort of plan did you come up with for the house?”

“I’ve got a surefire idea to get you all out of this mess,” Aunt Olympia said, taking a sip of tea. A bright smear of orange lipstick decorated the rim of her glass.

Surefire. That couldn’t be good. Aunt Olympia had flair, beauty, style and one of the finest Southern mansions in the state, but she had about the same amount of business sense as Lucy’s daddy. She knew how to spend money, not make it.

She leaned forward, resting her hand on Lucy’s. Her long nails were sunset orange with tiny black palm trees. “I called my friend Pearly Mae and she—”

Letting out a groan, Lucy slumped in the chair. “Oh, boy.”

Aunt Olympia paused, lips a thin line. “You can make all the fun you want, but Pearly Mae knows everything about everyone.”

“Now she knows everything about us, too.”

“Yes, well, that’s part of the bargain, isn’t it? You tell her what you need and she tries to help out.”

“While calling every friend of hers on the way.” Lucy had just enough pride left to be horrified at the idea of her family troubles being spread around town.

Ignoring that last comment, Aunt Olympia went on, “She heard that the Free Clinic of Tupelo needed a new space. They got a big grant from the state to upgrade all their equipment, but the place over on Yancey Avenue is too little for all their clientele. Crawford House has thirteen large bedrooms upstairs and—”

Lucy held up a hand, eyes closed. “Wait, now. Wait just a minute here.”

“I know you think they’ll destroy the place,” her aunt said. “But they won’t make any significant changes and you all can still live here, too.”

Lucy cracked an eye and stared at her. “Live here. With the Free Clinic of Tupelo.” She wasn’t sure which was worse: the idea of Crawford House being rented out as a medical facility or living in what would amount to a waiting room for sick people.

“You wouldn’t have to interact with them at all, of course. You and Willy keep the front part of the house with the library, sitting room, kitchen and your bedrooms. The back part could be turned into a reception area and consultation rooms.”

Something about her aunt’s wording rang a warning bell. “You’ve already been talking to someone about this? Someone other than Pearly Mae?”

“Lucy, it happened so fast, it must be God’s will.” Aunt Olympia sat forward beaming. “And Dr. Stroud says he knows you. Last Christmas he was here with his wife at Crawford House’s annual party, and you two stood by the punch bowl half the night, chatting about battlefield amputations.”

Lucy remembered Dr. Stroud. Bushy white mustache, bow tie, seersucker suit. She’d figured he was retired and no longer practicing medicine because he seemed to spend all his time on Civil War collections and reenactments. He’d said that he was surprised the African-American community wasn’t more involved with Brice’s Crossroads, since half of the Union dead were part of Bouton’s Brigade of United States Colored Troops, and then he’d tried to recruit her for the next battle. She’d wavered under his charm. The idea of battling mosquitoes in five layers of Civil War dress made it easy to say no.

She chewed the inside of her lip. If Aunt Olympia had named any other person in the area, she would never think of agreeing, but Dr. Stroud understood the history of a place like Crawford House. He wouldn’t be setting his coffee cup on the hundred-year-old white-oak fireplace mantel from Philadelphia, or hanging his coat from the cast-iron wall sconces.

“How much will they pay? And what are the terms of the lease?”

“See, I knew you would agree,” Aunt Olympia said. “It’s enough that you can pay off that home equity in a few years. They’ll be over in about fifteen minutes. I told him to give me a little time to get you comfy with the idea.”

“I’m not agreeing to anything. Daddy’s not even here to make a decision.” Lucy stood up, glancing around the kitchen. Mrs. Hardy only came on Tuesdays and Thursdays now. There were dishes in the sink, crumbs on the counters and her daddy’s coffee mugs dotted the drainboard.

As if following Lucy’s train of thought, Aunt Olympia wandered to the sink and stood in front of it, blocking the view of the mess. “Honey, I can convince Willy to do what’s right. I’m more worried about getting you on board. This is the best thing that could have happened. You won’t have to move, Willy can get out of debt and the house will be used for something other than gathering dust. Plus, I know Paulette is counting on having a big, fancy wedding as soon as she finds her man.”

Lucy leaned around her aunt and held a dishrag under the faucet, saying nothing. She wasn’t agreeing to this so that Paulette could have the wedding of the year when she finally chose between all her boyfriends.

“There is one small detail I should mention.” The tone of forced cheerfulness in her aunt’s voice made Lucy pause.

She turned, wet rag in one hand. “What? Will they put a sign on the front of the house? Install bars on the windows?”

“I’m not sure about any of that.” Aunt Olympia’s cheeks turned darker and the sight filled her with dread. Her aunt was never embarrassed. It was practically impossible to shame the woman. She firmly believed she was in the right at all times.

When Lucy didn’t respond, her aunt hurried on, “They’re bringing in a new doctor. He’s part of the Rural Physicians Scholarship Program, and now that he’s graduated, he’s coming back to practice in a rural community so he can erase his school debt.”

Lucy reached out for the back of the kitchen chair. She could hardly feel the smooth wooden top rail under her hand. Please, Lord. Not him. The kitchen had turned small, her aunt’s voice fading away. A flash of a crooked smile, blond hair tousled from the wind, a gentle voice, the warmth of large hands against her back.

“Honestly, it’s not a big deal.” Aunt Olympia let out a sigh as if her niece were being difficult.

“Who is it?” Even as she asked the question, Lucy knew the answer. Her aunt wouldn’t have saved this point for last if it wasn’t important.

“Jeremiah Chevy.” Her aunt reached out to pat Lucy’s hand, changing her mind when she saw the wet rag clenched in one of Lucy’s fists. “You’ll be fine. It’s been a long time. Ten years almost. It was the right thing to do and you know it. First of all, that name. Did you really want to be Mrs. Chevy?”

Lucy slid into a chair. Mrs. Chevy. She’d actually practiced that name on the inside cover of her school notebooks, over and over in her best handwriting. Mrs. Lucy Crawford Chevy.

Her aunt waved a hand, as if the concept had let off a terrible smell. “Can you imagine? It was insanity, being attached at eighteen to a boy like that.”

“Like what, Auntie?” Lucy could hear the trembling in her voice. She didn’t know if it was from shock or fury or both. “White? Poor? Or was it that Jem has a teen dropout for a mama?”

“Well, sure, all of those things.” Aunt Olympia wasn’t embarrassed now. “It never would have worked. He didn’t even know if he could get into college. I don’t know how he got through medical school, and he must have mountains of debt. Probably in the hundreds of thousands.”

Lucy stared at her aunt, wondering if the woman honestly believed medical-school debt was any worse than what her daddy had accrued with bad investments and lavish vacations.

“He had nothing but his daddy’s name, which he couldn’t trade for beans. And if you thought your mama would have been happy with you marrying a white boy, you’re wrong.”

Lucy felt her throat close up. Had her mama been a racist? She hadn’t said much at the time, not about his color. “Mama had green eyes. Someone somewhere didn’t care about color,” she whispered.

“Oh, don’t start with that. You know better.” Her aunt’s face was stony. “There’s no chance those pretty eyes came from a mixed couple in love a hundred years ago. Somebody knew the story but didn’t want to pass it down, and that tells us enough right there.”

Lucy dropped her chin to her chest. The news had sucked every logical thought from her head. Oh, the irony was laughable. She’d been persuaded to break it off with him because she was wealthy, Black and guaranteed a good job after being accepted to Harvard. Only one of those things was still true.

The doorbell sounded dimly in the distance.

“Oh, there they are,” her aunt said, jumping to her feet.

Lucy’s stomach turned to ice. “They?”

“Dr. Stroud and Jem. I can show them around if you want. I know you didn’t get a chance to put on anything nice.” Aunt Olympia paused, cocking her head. “And you haven’t been to the hairdresser’s in too long. You need one of those coconut-oil treatments under the hair dryer and maybe some extensions. You’re hardly fit to entertain guests. You just stay in the kitchen, hear?”

She sat frozen to the spot as Aunt Olympia sashayed out of the doorway. She would have given anything in the world to rewind the last ten minutes and keep this from happening. She would have called them, told them it wouldn’t work, made some excuse, any excuse.

Deep voices carried faintly to her and she wanted to clap her hands over her ears. She hadn’t heard anything from Jem in ten years. Not an e-mail, not a text. Completely understandable, really. Once they had been the best of friends, finishing each other’s sentences and talking for hours into the night. And love, there had always been love. She never let herself think of it, but now, in a flash, she remembered clearly the overwhelming need to be near him, to touch him. He was like air to her then, and she couldn’t live without him.

And yet, she had. When her aunt had convinced her it would never work out, Lucy had stood on his rickety front porch and told him she had decided it was better if they saw other people. It was such a stupid thing to say, something she copied from a TV show about teenagers who swapped boyfriends like shoes. There were no other people to see, was no one else she wanted, then or after. The memory of the shock and hurt on Jem’s face haunted her dreams, stole her appetite and gnawed away at her peace of mind. By the time she reached her breaking point months later, he was gone. There was nothing for her to do but sleep in the proverbial bed she had made.

The kitchen was silent except for the sound of her own breathing. Time seemed suspended, as if the world were waiting on her next move.

Lucy ran a hand over her hair, feeling the slight frizz at her hairline, the dryness at the ends. She wasn’t wearing much makeup, had only a pair of simple pearl studs in her ears. She glanced down, taking in her battered running shoes, straight-leg jeans and last year’s marathon T-shirt, which had a tiny hole at the hem. When she’d known Jem, she’d put in about the same amount of time on her appearance as any wealthy teenage girl. But after he’d gone, there wasn’t any reason to get her nails done or a facial at her favorite spa. She’d thrown herself into her studies and done her best to keep her mind off her heartache. This was who she was now. Putting off this meeting until she made it to the hairdresser’s implied that something could be changed. She heaved herself to her feet. There was no choice except to walk in there like the grown woman she was and welcome them into her home. “Please give me strength,” she whispered. And it would be nice if she didn’t trip, stutter, or blush.

It seemed to take hours to walk down the hallway, but finally she reached the end, emerging into the foyer. Her gaze landed on Dr. Stroud first, as he swept an arm out toward the seating in the entryway. He was saying something about the Civil War–era sewing bench and square nails.

Lucy tried to focus on Dr. Stroud, but her attention was pulled, against her will, to Jem. He was half-turned away, looking out the large windows onto the rose garden. At first glance, it was surreal to see him standing there in her house, as if ten years hadn’t passed. But a closer look showed the years between. Wearing a charcoal-gray suit that fit him well, his hands were at his sides. He was taller than she remembered. Bulkier around the shoulders, more heft and muscle. As a teen he had always managed to get his feet tied up in chair legs or trip over wrinkles in the carpet or bump his head on a low doorframe. He had changed, but was still the same, so much the same that she could have recognized him from the back. The muscles under his jacket tensed, and she knew that he would turn and see her. The moment before their eyes met, Lucy felt as if she were dangling off the side of a cliff, holding on to one slim branch as it bent toward the ground. If he let on, in any way, with a smirk or a glint of laughter, what a humorous reversal of fortune this was, she didn’t think she would survive.

He met her gaze steadily, emotionless. It was as if they didn’t know each other at all. His blond hair still stick-straight, brows two shades darker, the long nose he inherited from his mom’s side, the blue eyes from his dad’s Irish grandparents. She looked at him, not able to think of a word to say. She wanted to catalog his features, to spend hours noting every tiny difference from ten years ago, but he wasn’t hers and hadn’t been for a long time.

“Oh, here you are. Miss Lucy Crawford, let me introduce my colleague, Dr. Jeremiah Chevy. He’s just completed his residency at Boston Children’s Hospital.” Dr. Stroud beckoned her forward, bushy mustache twitching with excitement. “He’s also quite a fan of our local history. You might have crossed paths, with being the curator over at Brice’s Crossroads.”

“We’ve met before,” Jem said casually. “Nice to see you again.”

She nodded. “And you.”

He’d already looked away, gazing up at the high ceiling and the brass chandelier, probably noticing how shabby the ornate ceiling medallion looked, small bits of paint flaking off at the curves of the motif.

“Excellent. Then we’re all introduced and we can talk about the future of the Free Clinic.” Dr. Stroud clapped his hands together. “Miss Lucy, will you lead the way?”

She tried to look as if her pulse weren’t pounding in her ears. “My aunt said you’d like to look at the back of the house, near the former servants’ quarters?”

“Let’s start there. If the rooms are big enough, we can make them examination rooms.” Dr. Stroud glanced around. “What a magnificent old place. Your family must be incredibly proud.”

Proud. She cringed at the word. If they had been proud, her daddy would have made sure that their home was safe, instead of adding equity loan after equity loan on the old place. No bank in the state would forgive that kind of debt just because it was a Civil War–era home. They didn’t care that her great-granddaddy Whittaker had brought that pie safe all the way from Philadelphia or that her grandmama Honor had handpicked the wallpaper. Family history didn’t matter to a big bank, and if her daddy had been truly proud, then he would have been more careful.

“Follow me back, then.” She turned and crossed the foyer, knowing she would do whatever it took to save her home, but wishing with all her heart that this day had never come.

No: the years which had destroyed her youth and bloom had only given him a more glowing, manly, open look, in no respect lessening his personal advantages. She had seen the same Frederick Wentworth.

—ANNE ELLIOT

Chapter One

“?This is an effort to collect a debt. Any information obtained will be used for that purpose.”

Lucy Crawford leaned her forehead against the wall and closed her eyes. The mechanical voice droned on, rattling through an 800 number and requesting a call back. The time stamp was an hour ago.

There was a brief pause and the next message began: “This call is for William Crawford. I am a debt collector and this is an effort to collect a debt. Any information—”

Lucy reached out and punched the skip button. The message machine flashed three more calls in the queue. She didn’t know if she could listen to them all at one time. It was too depressing, like watching the recap, over and over, of the Bulldogs falling to Alabama by thirty points. Except that there was always next year for her favorite football team, and there wasn’t any end in sight to her daddy’s financial issues.

Skip. Skip. Skip. Maybe all the calls were from the same creditor, but probably not. Lucy heaved herself upright and trudged into the foyer. She might as well get the mail now while she was already feeling low. The black-and-white tile expanse of the entrance area gleamed dully in the summer light shining through the leaded panes of the double doors. In all of her twenty-eight years she had never seen them so scuffed. Old Zeke polished the floors of every room in the house once a week and always spent extra time on the entrance. He was proud of his job and being part of keeping up the historic Crawford House. Or at least he had been, until Lucy had fired him.

She paused in front of the side table, where a five-inch stack of bills waited neatly. The conversation with Zeke flashed through her mind and she felt the unfamiliar burn of tears. She wasn’t a crier. When she’d sat Zeke down, she had done well, speaking clearly and confidently until he had bowed his head. The defeat in his posture was like a stab of hot iron in her heart. Zeke had always seemed larger than his five-foot-five frame, probably because Lucy remembered being very little, pulling on his pant leg and looking far, far up at the Crawford House handyman. He was like family, and she was telling him he wasn’t going to be part of their daily lives any longer.

Then he had glanced up, black eyes still bright despite his seventy-five years. “Miss Lucy, I know’d this time be coming. I’s not as strong as I once was.”

She had wanted to drop to her knees, wrap her arms around his fragile shoulders and cry like a little girl. She’d wanted to cry like the time she’d lost her dolly down the irrigation pipe in the back pasture, before Zeke had retrieved it for her. Like the time she’d broken her heart into tiny pieces and he sat beside her, patting her shoulder and whispering, “There, there,” until she fell asleep, soggy and exhausted.

But she hadn’t. Lucy had explained, again, about the debts and the home equity loan and the repairs they couldn’t afford. No matter what she’d said about bills and bankruptcy and foreclosure, old Zeke hadn’t quite seemed convinced. The memory of it was so strong she felt chilled, even standing in the stifling air of the foyer. Lucy reached out and grabbed up the pile of envelopes, not even bothering to glance at the addresses. They wouldn’t be able to pay them, or any new ones that would have come in.

“Honey, is that you?” Her daddy’s rich baritone echoed through the large entrance hall. Seconds later he appeared around the corner, dressed in a perfectly pressed pair of yellow-and-green-plaid golf pants, Ralph Lauren polo shirt casually unbuttoned at the neck. Willy Crawford’s close-cropped hair was still black, except for a bit of gray at each temple, and for a man of sixty, he was still lean and fit. “I’m headed to the club for a quick round with Theon James.”

Lucy winced inside. Theon James excelled in three things: golf, business and goading her daddy into spending money to keep up his reputation as the richest man in town. She suspected Theon was playing a game, enjoying how easy it was to convince Willy Crawford that it was time to get a newer car or take a monthlong vacation to St. Simons Island.

“Will you be home for lunch? I have a casserole in the oven I think you’d really like, Daddy.”

He cocked an eyebrow. “Does it have any meat in it?”

She was tempted to lie. Really, he acted as if vegetarian cooking were poison. “No, but the eggplant tastes just like—”

“Nah.” He pulled on a matching green-and-yellow-plaid golfer’s cap and shouldered his bag. “You know I don’t like that sort of thing. Put some ham in it next time. And don’t say I always need my meat, because I eat some of that vegetarian food, too. Your mama was a great cook. Her beignets were so light and fluffy, fried just right, a good bit of powdered sugar on top. . . .” He paused, a small smile on his face. Lucy knew just what he felt. Sweet memories were all they had left of her mama.

“Before you go,” she started to say, holding out the mail. ?He cut her off. “No time now, sugar. Theon’s already there.” Her daddy leaned in and gave her a quick kiss on the head, leaving a whiff of Old Spice and cigars.

“It’s just I thought you were fixin’ to sort through some of these on Sunday after church, but you went out to lunch. We need to see if there are a few we could pay off right away. It would save a lot on interest in the long run and . . .”

He wasn’t listening to her. Bending over his golf bag, he rummaged inside. “When I get back, I’ll take care of it. And there’s no we about payin’ these bills. I’ve got the money, just need to cash out a few old savings accounts and I’ll be settled up with those people.”

Lucy almost sighed out loud. Those people. Her daddy always drew a thick black line between their family and the rest of the world. If she tried to suggest that they were close to bankruptcy, he would point out how the Crawfords had owned the finest home in Brice’s Crossroads, Mississippi, since right after the Civil War had ended, or how his great-granddaddy had founded the area’s first African-American business league, or how the Crawfords had attended Harvard before the Roosevelts. The Crawfords were good stock. They were on the boards of hospitals, joined exclusive clubs, were admired by everyone. They didn’t have financial issues, and they certainly didn’t worry out loud if they did.

“Some of these are probably Paulette’s,” Lucy said. “You’ve got to get those credit cards from her. She’s got closets full of designer clothes and she just buys more.”

“Your sister is a fine-lookin’ woman in search of a husband. I won’t be interfering with that.” He winked at her.

“But Janessa managed to get a husband without spending sprees in Atlanta.” Lucy crossed her arms over her chest. Her middle sister had many faults, but being a fashionista wasn’t one of them.

“You leave Paulette be. She’s not like you. She’s still young and hasn’t given up on men. I don’t mind her spending a bit to make herself look presentable. It’s part of keeping up appearances. She certainly doesn’t want to live in her daddy’s house the rest of her days.” His voice was light, but there was a warning in his eyes.

Did he think she’d given up on men? She swallowed past the hurt of his words and said, “Alrighty, as soon as you get back, let’s go over these bills together. Mama’s not here. You need to keep track of these things.”

“Don’t be disrespectful.” His face was stiff with anger. “I didn’t raise you like that.”

Lucy dropped her gaze to the floor. When she was little, her daddy had heard her mouth off to her mama. He hadn’t used the switch on her, the way she’d thought he would. He’d sat her on his knee and explained he could forgive a lot of sins, but he could never love a stubborn, strong-willed girl. She’d apologized to her mama and tried her very best to be a good girl ever since. She was a grown woman now, but Lucy still couldn’t seem to balance on that fence between gentle coaxing and shrewish nagging.

“I didn’t mean to offend, Daddy.”

The door was already closing on the end of her sentence, and Lucy listened to him cross the wide, wooden porch. His footsteps faded with each step toward his shiny red Miata. She sagged against the side table and resisted the urge to throw the whole stack of letters against the door. He wouldn’t listen. She had done everything possible to keep the bank from foreclosing on the house, but it was only a matter of time before they lost everything. Her mama had been so good at managing the household finances. Maybe too good. Her daddy had been happy to turn it all over to her and focus on his golf game. He was the face of Crawford Investments, but her mama had been the brains. When she passed, he’d just pretended that nothing had changed, creating chaos at home and disaster for the business.

Just the thought of her mama gave Lucy a sharp pain, even though it had been close to nine years now she’d been gone. One early morning she’d collapsed in the kitchen and Lucy’s life had changed forever.

Lucy breathed a prayer of thanksgiving for the time they’d had together, all the way through her teens. She used to love sitting in the bright-blue kitchen and watching her mama cook. Their housekeeper, Mrs. Hardy, made perfectly fine meals, but her mama wasn’t happy if she didn’t mix up a batch of gumbo or hush puppies once in a while. Straight from Cane River, she spoke with the lyrical accent of a native Creole speaker and had eyes the color of Kentucky bluegrass. She liked to sing, all the time, and it was like having a radio you could never turn off. Gospel hymns, blues, low-country ballads. The house was so quiet without her. Lucy had the dark eyes and skin of her daddy, but her curves and throaty laugh were all her mama’s doing.

She still had the curves, but it had been months since she’d heard herself laugh.

A rap at the door sounded like a gunshot in the quiet foyer. Lucy hesitated, wondering if bill collectors ever came to the door in their “attempts to collect a debt.” Peeking through the beveled glass, she let out a breath. When trouble comes, family arrives close behind, for better or for worse.

“Auntie,” she said, swinging the door wide.

Aunt Olympia held out both hands and stuck out her lower lip. “Oh, honey, come here.” She gripped Lucy’s hands and hauled herself over the threshold like a shipwreck victim grabbing hold of a life raft.

“You got my message,” Lucy said into her aunt’s elaborately braided updo. Lucy was being squeezed and rocked from side to side, and her words sounded as if she were running.

“Yes, bless your heart. And I’ve been busy solving your problems,” Aunt Olympia said. Letting go of Lucy, she shut the door behind her and started toward the kitchen. “Come let me tell you all about it over a little sweet tea.”

Lucy knew better than to laugh. There was no way Aunt Olympia could have solved anything in the hours since Lucy had called, giving the dire news of the impending foreclosure. Instead, Lucy trailed along behind her, wondering how such a tiny woman could exude such force. Where Olympia went, everyone followed.

“Aren’t you supposed to be at the museum today?” her aunt called over one shoulder. Of course she would have noticed Lucy’s jeans-and-T-shirt ensemble right away. Her aunt didn’t believe in casual clothes. Her neon-green track suit said JUICY on the rear, and her earrings bounced with every movement. She was all flash, all the time.

“They’re closed for maintenance, and it’s an interpretive center, not a museum.” Lucy didn’t want to talk about her job. Aunt Olympia would say Lucy should have a better position, maybe something with a fancy title and a yearly bonus.

“Which means what? Cleaning?” Aunt Olympia moved around the cheery kitchen, reaching into the fridge for the pitcher of tea.

Lucy dropped into a chair. “Yes. Cleaning.” Maintenance made it sound as if the center might get a new roof or any of the other desperately needed repairs. But upgrading access to a Civil War battlefield site wasn’t high on the list of popular causes in Tupelo.

“I don’t know why you work over there. You probably are only gettin’ the people who wander through from the Elvis museum.”

Lucy said nothing. The sad fact was, if Elvis had been born in Brice’s Crossroads, they’d have an event center with a full kitchen, green rooms and a theater—not to mention a chapel and a gift shop with its own apparel line. As it was, they had to make do with folding chairs, a microwave and a yearly budget that wouldn’t cover Graceland’s electric bill.

“Hun, you need to find yourself a better job. Iola is working on the top floor of a smoked-glass high-rise in Atlanta. She wears the prettiest outfits and has a whole closet for her shoes. She says—”

“I know,” Lucy interrupted, unable to stand hearing one more time about her cousin’s happiness at being a secretary for a group of slick lawyers in pin-striped suits. “I know,” she said more slowly. “But working at the center is perfect for me, Auntie. I love this area, these people. If I could have majored in the history of Tupelo, Mississippi, I would have. Being a curator doesn’t come with fame or glory, but it makes me happy.”

Aunt Olympia’s frown softened into a sigh. “You deserve a little happiness, that’s for sure.”

Lucy wondered for a moment if she meant because of the way her mama had passed away so suddenly, or if Olympia was talking about another time, long before. An image of a laughing, blond-haired boy flashed through her mind and she shoved it away. Her present was bad enough without wallowing in the past.

Her aunt glanced in the oven. “Is that lasagna? You know your daddy doesn’t like ethnic dishes.”

“It’s baked ziti, and he’s already taken a pass.”

“Oh, honey, you need to learn how to cook. You’re never going to catch a man with that kind of food.” Aunt Olympia shook her head, as if knowing the perfect fried chicken recipe would solve Lucy’s single status.

She didn’t want the conversation to veer off into marriage talk. “What sort of plan did you come up with for the house?”

“I’ve got a surefire idea to get you all out of this mess,” Aunt Olympia said, taking a sip of tea. A bright smear of orange lipstick decorated the rim of her glass.

Surefire. That couldn’t be good. Aunt Olympia had flair, beauty, style and one of the finest Southern mansions in the state, but she had about the same amount of business sense as Lucy’s daddy. She knew how to spend money, not make it.

She leaned forward, resting her hand on Lucy’s. Her long nails were sunset orange with tiny black palm trees. “I called my friend Pearly Mae and she—”

Letting out a groan, Lucy slumped in the chair. “Oh, boy.”

Aunt Olympia paused, lips a thin line. “You can make all the fun you want, but Pearly Mae knows everything about everyone.”

“Now she knows everything about us, too.”

“Yes, well, that’s part of the bargain, isn’t it? You tell her what you need and she tries to help out.”

“While calling every friend of hers on the way.” Lucy had just enough pride left to be horrified at the idea of her family troubles being spread around town.

Ignoring that last comment, Aunt Olympia went on, “She heard that the Free Clinic of Tupelo needed a new space. They got a big grant from the state to upgrade all their equipment, but the place over on Yancey Avenue is too little for all their clientele. Crawford House has thirteen large bedrooms upstairs and—”

Lucy held up a hand, eyes closed. “Wait, now. Wait just a minute here.”

“I know you think they’ll destroy the place,” her aunt said. “But they won’t make any significant changes and you all can still live here, too.”

Lucy cracked an eye and stared at her. “Live here. With the Free Clinic of Tupelo.” She wasn’t sure which was worse: the idea of Crawford House being rented out as a medical facility or living in what would amount to a waiting room for sick people.

“You wouldn’t have to interact with them at all, of course. You and Willy keep the front part of the house with the library, sitting room, kitchen and your bedrooms. The back part could be turned into a reception area and consultation rooms.”

Something about her aunt’s wording rang a warning bell. “You’ve already been talking to someone about this? Someone other than Pearly Mae?”

“Lucy, it happened so fast, it must be God’s will.” Aunt Olympia sat forward beaming. “And Dr. Stroud says he knows you. Last Christmas he was here with his wife at Crawford House’s annual party, and you two stood by the punch bowl half the night, chatting about battlefield amputations.”

Lucy remembered Dr. Stroud. Bushy white mustache, bow tie, seersucker suit. She’d figured he was retired and no longer practicing medicine because he seemed to spend all his time on Civil War collections and reenactments. He’d said that he was surprised the African-American community wasn’t more involved with Brice’s Crossroads, since half of the Union dead were part of Bouton’s Brigade of United States Colored Troops, and then he’d tried to recruit her for the next battle. She’d wavered under his charm. The idea of battling mosquitoes in five layers of Civil War dress made it easy to say no.

She chewed the inside of her lip. If Aunt Olympia had named any other person in the area, she would never think of agreeing, but Dr. Stroud understood the history of a place like Crawford House. He wouldn’t be setting his coffee cup on the hundred-year-old white-oak fireplace mantel from Philadelphia, or hanging his coat from the cast-iron wall sconces.

“How much will they pay? And what are the terms of the lease?”

“See, I knew you would agree,” Aunt Olympia said. “It’s enough that you can pay off that home equity in a few years. They’ll be over in about fifteen minutes. I told him to give me a little time to get you comfy with the idea.”

“I’m not agreeing to anything. Daddy’s not even here to make a decision.” Lucy stood up, glancing around the kitchen. Mrs. Hardy only came on Tuesdays and Thursdays now. There were dishes in the sink, crumbs on the counters and her daddy’s coffee mugs dotted the drainboard.

As if following Lucy’s train of thought, Aunt Olympia wandered to the sink and stood in front of it, blocking the view of the mess. “Honey, I can convince Willy to do what’s right. I’m more worried about getting you on board. This is the best thing that could have happened. You won’t have to move, Willy can get out of debt and the house will be used for something other than gathering dust. Plus, I know Paulette is counting on having a big, fancy wedding as soon as she finds her man.”

Lucy leaned around her aunt and held a dishrag under the faucet, saying nothing. She wasn’t agreeing to this so that Paulette could have the wedding of the year when she finally chose between all her boyfriends.

“There is one small detail I should mention.” The tone of forced cheerfulness in her aunt’s voice made Lucy pause.

She turned, wet rag in one hand. “What? Will they put a sign on the front of the house? Install bars on the windows?”

“I’m not sure about any of that.” Aunt Olympia’s cheeks turned darker and the sight filled her with dread. Her aunt was never embarrassed. It was practically impossible to shame the woman. She firmly believed she was in the right at all times.

When Lucy didn’t respond, her aunt hurried on, “They’re bringing in a new doctor. He’s part of the Rural Physicians Scholarship Program, and now that he’s graduated, he’s coming back to practice in a rural community so he can erase his school debt.”

Lucy reached out for the back of the kitchen chair. She could hardly feel the smooth wooden top rail under her hand. Please, Lord. Not him. The kitchen had turned small, her aunt’s voice fading away. A flash of a crooked smile, blond hair tousled from the wind, a gentle voice, the warmth of large hands against her back.

“Honestly, it’s not a big deal.” Aunt Olympia let out a sigh as if her niece were being difficult.

“Who is it?” Even as she asked the question, Lucy knew the answer. Her aunt wouldn’t have saved this point for last if it wasn’t important.

“Jeremiah Chevy.” Her aunt reached out to pat Lucy’s hand, changing her mind when she saw the wet rag clenched in one of Lucy’s fists. “You’ll be fine. It’s been a long time. Ten years almost. It was the right thing to do and you know it. First of all, that name. Did you really want to be Mrs. Chevy?”

Lucy slid into a chair. Mrs. Chevy. She’d actually practiced that name on the inside cover of her school notebooks, over and over in her best handwriting. Mrs. Lucy Crawford Chevy.

Her aunt waved a hand, as if the concept had let off a terrible smell. “Can you imagine? It was insanity, being attached at eighteen to a boy like that.”

“Like what, Auntie?” Lucy could hear the trembling in her voice. She didn’t know if it was from shock or fury or both. “White? Poor? Or was it that Jem has a teen dropout for a mama?”

“Well, sure, all of those things.” Aunt Olympia wasn’t embarrassed now. “It never would have worked. He didn’t even know if he could get into college. I don’t know how he got through medical school, and he must have mountains of debt. Probably in the hundreds of thousands.”

Lucy stared at her aunt, wondering if the woman honestly believed medical-school debt was any worse than what her daddy had accrued with bad investments and lavish vacations.

“He had nothing but his daddy’s name, which he couldn’t trade for beans. And if you thought your mama would have been happy with you marrying a white boy, you’re wrong.”

Lucy felt her throat close up. Had her mama been a racist? She hadn’t said much at the time, not about his color. “Mama had green eyes. Someone somewhere didn’t care about color,” she whispered.

“Oh, don’t start with that. You know better.” Her aunt’s face was stony. “There’s no chance those pretty eyes came from a mixed couple in love a hundred years ago. Somebody knew the story but didn’t want to pass it down, and that tells us enough right there.”

Lucy dropped her chin to her chest. The news had sucked every logical thought from her head. Oh, the irony was laughable. She’d been persuaded to break it off with him because she was wealthy, Black and guaranteed a good job after being accepted to Harvard. Only one of those things was still true.

The doorbell sounded dimly in the distance.

“Oh, there they are,” her aunt said, jumping to her feet.

Lucy’s stomach turned to ice. “They?”

“Dr. Stroud and Jem. I can show them around if you want. I know you didn’t get a chance to put on anything nice.” Aunt Olympia paused, cocking her head. “And you haven’t been to the hairdresser’s in too long. You need one of those coconut-oil treatments under the hair dryer and maybe some extensions. You’re hardly fit to entertain guests. You just stay in the kitchen, hear?”

She sat frozen to the spot as Aunt Olympia sashayed out of the doorway. She would have given anything in the world to rewind the last ten minutes and keep this from happening. She would have called them, told them it wouldn’t work, made some excuse, any excuse.

Deep voices carried faintly to her and she wanted to clap her hands over her ears. She hadn’t heard anything from Jem in ten years. Not an e-mail, not a text. Completely understandable, really. Once they had been the best of friends, finishing each other’s sentences and talking for hours into the night. And love, there had always been love. She never let herself think of it, but now, in a flash, she remembered clearly the overwhelming need to be near him, to touch him. He was like air to her then, and she couldn’t live without him.

And yet, she had. When her aunt had convinced her it would never work out, Lucy had stood on his rickety front porch and told him she had decided it was better if they saw other people. It was such a stupid thing to say, something she copied from a TV show about teenagers who swapped boyfriends like shoes. There were no other people to see, was no one else she wanted, then or after. The memory of the shock and hurt on Jem’s face haunted her dreams, stole her appetite and gnawed away at her peace of mind. By the time she reached her breaking point months later, he was gone. There was nothing for her to do but sleep in the proverbial bed she had made.

The kitchen was silent except for the sound of her own breathing. Time seemed suspended, as if the world were waiting on her next move.

Lucy ran a hand over her hair, feeling the slight frizz at her hairline, the dryness at the ends. She wasn’t wearing much makeup, had only a pair of simple pearl studs in her ears. She glanced down, taking in her battered running shoes, straight-leg jeans and last year’s marathon T-shirt, which had a tiny hole at the hem. When she’d known Jem, she’d put in about the same amount of time on her appearance as any wealthy teenage girl. But after he’d gone, there wasn’t any reason to get her nails done or a facial at her favorite spa. She’d thrown herself into her studies and done her best to keep her mind off her heartache. This was who she was now. Putting off this meeting until she made it to the hairdresser’s implied that something could be changed. She heaved herself to her feet. There was no choice except to walk in there like the grown woman she was and welcome them into her home. “Please give me strength,” she whispered. And it would be nice if she didn’t trip, stutter, or blush.

It seemed to take hours to walk down the hallway, but finally she reached the end, emerging into the foyer. Her gaze landed on Dr. Stroud first, as he swept an arm out toward the seating in the entryway. He was saying something about the Civil War–era sewing bench and square nails.

Lucy tried to focus on Dr. Stroud, but her attention was pulled, against her will, to Jem. He was half-turned away, looking out the large windows onto the rose garden. At first glance, it was surreal to see him standing there in her house, as if ten years hadn’t passed. But a closer look showed the years between. Wearing a charcoal-gray suit that fit him well, his hands were at his sides. He was taller than she remembered. Bulkier around the shoulders, more heft and muscle. As a teen he had always managed to get his feet tied up in chair legs or trip over wrinkles in the carpet or bump his head on a low doorframe. He had changed, but was still the same, so much the same that she could have recognized him from the back. The muscles under his jacket tensed, and she knew that he would turn and see her. The moment before their eyes met, Lucy felt as if she were dangling off the side of a cliff, holding on to one slim branch as it bent toward the ground. If he let on, in any way, with a smirk or a glint of laughter, what a humorous reversal of fortune this was, she didn’t think she would survive.

He met her gaze steadily, emotionless. It was as if they didn’t know each other at all. His blond hair still stick-straight, brows two shades darker, the long nose he inherited from his mom’s side, the blue eyes from his dad’s Irish grandparents. She looked at him, not able to think of a word to say. She wanted to catalog his features, to spend hours noting every tiny difference from ten years ago, but he wasn’t hers and hadn’t been for a long time.

“Oh, here you are. Miss Lucy Crawford, let me introduce my colleague, Dr. Jeremiah Chevy. He’s just completed his residency at Boston Children’s Hospital.” Dr. Stroud beckoned her forward, bushy mustache twitching with excitement. “He’s also quite a fan of our local history. You might have crossed paths, with being the curator over at Brice’s Crossroads.”

“We’ve met before,” Jem said casually. “Nice to see you again.”

She nodded. “And you.”

He’d already looked away, gazing up at the high ceiling and the brass chandelier, probably noticing how shabby the ornate ceiling medallion looked, small bits of paint flaking off at the curves of the motif.

“Excellent. Then we’re all introduced and we can talk about the future of the Free Clinic.” Dr. Stroud clapped his hands together. “Miss Lucy, will you lead the way?”

She tried to look as if her pulse weren’t pounding in her ears. “My aunt said you’d like to look at the back of the house, near the former servants’ quarters?”

“Let’s start there. If the rooms are big enough, we can make them examination rooms.” Dr. Stroud glanced around. “What a magnificent old place. Your family must be incredibly proud.”

Proud. She cringed at the word. If they had been proud, her daddy would have made sure that their home was safe, instead of adding equity loan after equity loan on the old place. No bank in the state would forgive that kind of debt just because it was a Civil War–era home. They didn’t care that her great-granddaddy Whittaker had brought that pie safe all the way from Philadelphia or that her grandmama Honor had handpicked the wallpaper. Family history didn’t matter to a big bank, and if her daddy had been truly proud, then he would have been more careful.

“Follow me back, then.” She turned and crossed the foyer, knowing she would do whatever it took to save her home, but wishing with all her heart that this day had never come.

Product Details

- Publisher: Howard Books (December 1, 2014)

- Length: 304 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476777535

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“I love this excellent retelling of Jane Austen's Persuasion. I may even love it more than Persuasion . . . It was refreshing to see romantic references that weren't contrived. They were touching and believable and the characters were likeable--or hateable!”

– Hope In Every Season

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Persuasion, Captain Wentworth and Cracklin' Cornbread Trade Paperback 9781476777535

- Author Photo (jpg): Mary Jane Hathaway Photograph courtsey of the author(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit