Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

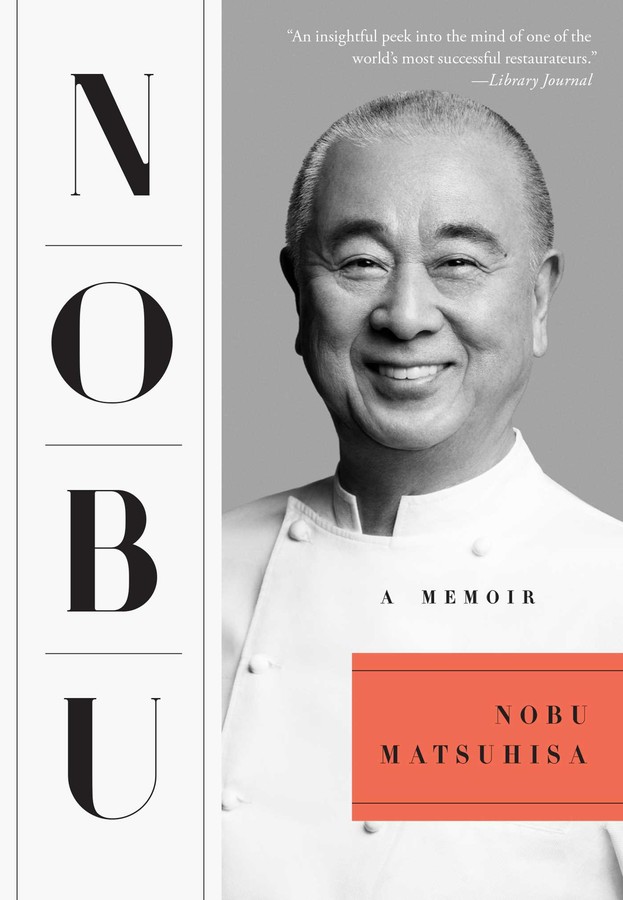

“Inspiration by example” (Associated Press) from the acclaimed celebrity chef and international restaurateur, Nobu, as he divulges both his dramatic life story and reflects on the philosophy and passion that has made him one of the world’s most widely respected Japanese fusion culinary artists.

As one of the world’s most widely acclaimed restaurateurs, Nobu’s influence on food and hospitality can be found at the highest levels of haute-cuisine to the food trucks you frequent during the work week—this is the Nobu that the public knows.

But now, we are finally introduced to the private Nobu: the man who failed three times before starting the restaurant that would grow into an empire; the man who credits the love and support of his family as the only thing keeping him from committing suicide when his first restaurant burned down; and the man who values the busboy who makes sure each glass is crystal clear as highly as the chef who slices the fish for Omakase perfectly.

What makes Nobu special, and what made him famous, is the spirit of what exists on these pages. He has the traditional Japanese perspective that there is great pride to be found in every element of doing a job well—no matter how humble that job is. Furthermore, he shows us repeatedly that success is as much about perseverance in the face of adversity as it is about innate talent.

Not just for serious foodies, this “insightful peek into the mind of one of the world’s most successful restaurateurs” (Library Journal) is perfect for fans of Marie Kondo’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up and Danny Meyer’s Setting the Table. Nobu’s writing does what he does best—it marries the philosophies of East and West to create something entirely new and remarkable.

Excerpt

Thanks to my years as an apprentice

LONGING TO TRAVEL LIKE MY FATHER

I don’t remember my childhood in much detail. Instead, fragmented images flash through my mind.

My father ran a lumber business in Sugito, a town in Saitama Prefecture. Sometimes he went overseas to buy lumber. He must have been a busy man. The last of his four children, I have almost no memories of playing with him. What I do remember is the warmth of his back when I rode behind him on his motorcycle. He often took me with him when he went places for work. It was the 1950s, and much of Saitama remained undeveloped. I loved speeding through the beautiful countryside, slicing through the wind while clinging to the back of this man whom I admired so much.

One day, I returned home from school to find my father about to leave. I held on to the back of his motorcycle and insisted that he take me, too. I must have really pestered him, because I remember that someone finally took a photo of us together, my father astride the bike and me standing on the back with my hands on his shoulders. But my father said he was going too far to take me with him and left alone. I can still see his back receding into the distance . . . It was a June afternoon, just two months after I began elementary school.

The next image is of my father in a hospital bed, covered in blood and groaning in pain. He’d been in an accident. This scene is followed by one of his funeral. Many relatives were there.

My memories jump like this from one scene to another.

Never again would I cling to my father’s back and ride through the wind. Never again would he hoist me onto his shoulders. Never again would we play catch together. I think it took some time for this to sink in.

I was so jealous when I saw my friends riding on their fathers’ shoulders or playing catch together. Sometimes I felt lonely, wondering why my father had to die. At those times, I would look at his photo. In it, he’s standing in front of what looks like a palm tree. Beside him is a local man dressed only in a loincloth. Later, I learned that this photo was taken during the Second World War when my father went to Palau to buy lauan wood. In those days, few Japanese civilians traveled overseas on business. I was very proud of him for traveling all alone to unexplored territory. And I felt the pull of distant lands myself. “When I grow up, I want to go overseas just like my father,” I thought. That was my first dream.

INHERITING MY GRANDMOTHER’S FIGHTING SPIRIT

The Matsuhisa family had lost its main breadwinner. My mother must have been at a complete loss when my father died so suddenly. Although she had helped him with his work, she didn’t even know the price of the company’s products. Once I remember her saying, “Your father came to see me last night.” Perhaps she had dreamed of him.

The customers demanded to know what she was going to do. She consulted my eldest brother, Noboru, who was then in grade twelve, but my second-eldest brother, Keiichi, intervened. “Let him graduate from high school,” he said. “I’ll take a year off.” He helped my mother until Noboru graduated the following spring and then reenrolled in grade ten while Noboru took over the company.

Noboru’s grades were good, and he had planned to go on to university and become a doctor. My father’s death, however, meant that he had to give up this dream. For a while, he became quite sullen and angry, perhaps due to the stress. Sometimes he drank and vented his frustration on my mother. In retrospect, I can see how hard it must have been for both of them.

Because of our situation, I spent most of my time with my grandmother. Born in the Meiji era (1868–1912), a time of great social upheaval in Japan, she was strong-willed and an avid pro wrestling fan. Rikidozan was her favorite wrestler. One day, I got into a fight and came home crying. She scolded me, but not for fighting or for crying. In those days, schoolboys still wore geta, or heavy wooden sandals. “Why did you come back with your geta on?” she demanded. “If they made you mad enough to cry, at least throw your geta at them before coming home!” Perhaps it’s from her that I inherited my fighting spirit, which forces me back on my feet whenever I fall.

THE DAY I DECIDED TO BECOME A SUSHI CHEF

When I was a child, I slept near the kitchen. I would wake every morning to the tap-tap of the knife on the cutting board, the scraping of the pot against the burner, the sound of water gushing from the kitchen faucet, and the savory aroma of soup stock and miso as my mother made soup. She was the old-fashioned type of housewife who kneaded the fermented rice bran in the pickling crock every day. She was a good cook, too. Although not the type to make elaborate, time-consuming dishes, she could whip up a meal without wasting time and effort, using whatever ingredients happened to be on hand. It made her happy to see us enjoy her cooking. She must have been incredibly busy, juggling both the business and the housework, but mealtime when I was a boy was fun. My first memories of food come from the joy of our family gathered around the dinner table.

The photo of my father that I always looked at as a child.

One day, my eldest brother, Noboru, took me to Uokou, a sushi bar in front of the local train station. It must have been when I was still in junior high school. Back then, sushi was a special treat ordered in for guests, and we would be lucky to get any that was left over. There was no such thing as conveyor belt sushi, and going to a sushi restaurant was extra special. I expect that I behaved like a spoiled brat and insisted that Noboru take me. He ducked under the noren (shop curtain) and slid open the door. I peered around him to see inside. The sushi chefs behind the counter called out, “Irasshai!” (meaning “welcome”). I felt very nervous, as if I were sneaking into an adult world where kids didn’t belong. Yet, at the same time, I was spellbound by the microcosm of the sushi bar into which I had stepped for the first time in my life.

Seeing how nervous I was, Noboru ordered for me. The distinctive fragrance of vinegared rice and the swift, unerring movements of the chefs captivated me. “Toro, gyoku, shako, agari, sabi . . .” I hadn’t a clue what they were saying, but the sound of the words that flew back and forth made my heart sing. Then, pieces of sushi, made especially for me, were placed on the counter, and I popped them in my mouth. They were really and truly delicious.

The restaurant, the movements of the sushi chefs, the exchanges across the counter, the conversations among the customers themselves, the sheen of the sushi toppings, the aroma of sushi rice . . . It was all the coolest thing ever. I decided then and there that I wanted to become a sushi chef. This became my second dream.

Before that, I had been drawn to such professions as gym teacher or soldier in the Self-Defense Forces. These worlds seemed dynamic and disciplined. Actually, I now see that they share something in common with the precise movements of a sushi chef. Those were the kinds of things that attracted me when I was young. But although I was drawn to foreign lands and sushi, it did not yet occur to me to choose a path in life that would fulfill those dreams. I had been born into the lumber business and, just like Keiichi, my second-eldest brother, I went on to Omiya Technical High School. There I joined the boys’ cheerleading squad. Again, I think I chose it because I loved dynamic action.

DRIVING WITHOUT A LICENSE AND GETTING EXPELLED FROM SCHOOL

I fell in with the wrong crowd in my hometown. When I was in eleventh grade, a gang of friends gathered at my house the night before our end-of-term exams. Supposedly, we were going to study, but once everyone else in the house was asleep, we decided to take Keiichi’s car out for a spin. I snuck the key from his room and started the engine. Of course, none of us had a license to drive.

I got behind the wheel and drove out onto National Route 4. It was the middle of the night, but there was more traffic than I had expected. It was 1963, the year before the first Tokyo Olympics, and construction was booming in Tokyo. Dump trucks zoomed back and forth day and night. There is nothing scarier than a cocky driver without a license. I pulled out and passed one truck after another. But when I tried to pass one more, I slammed into a car coming from the opposite direction. Our vehicle flipped and then rolled several times before it was hit by another car.

Ambulances and police cars soon arrived on the scene. At the sight of the damage, a policeman asked, “Where are the bodies?” My friends and I were shaking uncontrollably, certain that our lives were over. Amazingly, however, all of us, including me, were unscathed, and the people in the other vehicles had escaped with only minor injuries. It was nothing short of a miracle. The memory of that crash still sends shivers down my spine. I am convinced that my father protected us.

Since then I have had several other close shaves that make me shudder, experiences where one wrong move would have ended my life. Yet each time, some invisible power has saved me in ways that can only be described as miraculous. And each time, I have felt that my father was watching out for me.

I used to talk to my father’s photo when things weren’t going well, especially when I was younger. To be honest, I spent most of my time complaining rather than praying to him. “Why’d you have to go and die?” I would say. “Why aren’t you here to help me now when things are so rough?” As I talked, I would feel a weight lift from my chest. Recently, I have finally reached the stage where, instead of complaining, I place my palms together and thank him from the bottom of my heart. Perhaps it’s a sign that I’ve finally grown up.

But to return to my story, the day after the accident, I didn’t sit for the exams. Having been informed of what happened, the school understandably expelled me. They really had no choice considering that I had caused a major accident. To top it off, the court ordered that I was to be placed under probation until the age of twenty. My mother must have been worried sick, yet instead of reproaching me, she never mentioned the accident. I think the fact that she believed in me is what kept me from taking the wrong path. I began helping out with the family business instead of going to school, but my dream of becoming a sushi chef did not fade.

THREE YEARS OF WASHING DISHES AND DELIVERING SUSHI

I’m pretty sure that I consulted my mother or Noboru about my aspirations. The master of Uokou, the sushi bar in front of our local station where Noboru had once taken me, introduced me to the owner of a sushi bar in Shinjuku. As I had no way of judging which shop was a good one, I went where I was told. On June tenth, in my seventeenth year, I took my first step as an apprentice chef at Matsuei-sushi.

I had never lived away from home before, but now I shared one large room in the back of the restaurant with the two other staff. The sushi bar was closed just two days a month, and those were our only days off. Because we were live-in staff, there was a curfew. Even on our holidays, we had to be back by ten at night. The owner and his wife were quite strict about this, probably because I was underage and they felt responsible. My workday began early in the morning. Every day, I got on the bus with my boss and headed to the Tsukiji fish market. I followed after him with a basket to carry the fish he bought. I learned how to tell a good fish by watching him choose.

This was also a time of day when I could enjoy small acts of kindness. A vegetable broker might give me a bun to eat, or sometimes my boss would buy me something I could never have afforded. I still remember the times he treated me to eel or pork cutlet on curry and rice.

Back at the restaurant, it was time to prepare. For me, food prep consisted of the most basic tasks, such as scaling and beheading small fish. I was not particularly skillful with my hands. My only strength was my determination to keep up with the others. I couldn’t stand being beaten even at such simple tasks as prepping shad or conger eel. The fishermen at Tsukiji market could dress a fish with a few fluid movements, and I often watched them while they worked, hoping to learn how they did it so quickly and efficiently.

Once prep work was done, my coworkers would start grilling eel, and the owner’s wife would mix the sushi rice. Then it was lunch hour. When the sushi bar was open, I was stationed at the far end of the counter where I washed dishes, made tea, grated wasabi, and cut leaf garnishes. I also delivered takeout orders.

A COMBINATION PLATTER FOR BASEBALL STAR SADAHARU OH

Before I could start delivering orders on my own, I first had to learn where all the customers lived. One of them was homerun king Sadaharu Oh, who played for the Yomiuri Giants. My boss was a graduate of Waseda Jitsugyo High School and so was Oh. Through this connection, Oh had become a regular, and an autographed photo of him hung on the wall in the restaurant.

At the time, Oh was the main batter for the Giants but had not yet attained international fame. He wasn’t married yet, either. When he finished a game at Korakuen Stadium, his mother would phone us and order “the usual for Sadaharu.” Matsuei-sushi had a special combination platter of sushi and sashimi just for Oh. The boss would make it, and I would deliver it. Sometimes Oh would drive up just as I arrived, and I would direct him as he backed into the driveway.

Although I was nominally an apprentice sushi chef, I spent the first three years washing dishes and making deliveries. Some of my high school friends were now working, and they brought their girlfriends to the restaurant when they got their paychecks, but I had no skills with which to impress them. While I was happy that they had come especially to see me, I also felt a bit embarrassed.

Whenever I had a chance between tasks, I studied my boss and the other staff as they made sushi. I would roll up a small cloth, pretend it was sushi rice, and mimic their hand movements. On holidays, I would sometimes ask the boss for the leftover sushi rice so that I could practice. My days off, however, began with making the rounds of people who had ordered deliveries the previous day. I would collect the dishes and check that the money matched the orders. Then I tackled several days’ worth of laundry. By then, it was usually evening. That was the only free time I had.

My boss lived with his wife, his mother, his two sons, and his daughter. Sometimes I was asked to take his youngest son to kindergarten or to pick him up afterwards. On days when the restaurant was closed, the boss’s family would prepare their dinner in the evening. I remember seeing them sitting around the table enjoying a meal of sukiyaki, but my coworkers and I were not included in that circle. Perhaps I still remember because I envied them. And perhaps I was a bit lonely.

On days off, we had a few hours of freedom in the evening after we finished doing all our chores. The other two went drinking, but being underage, I couldn’t. Instead, I would go to the movies. There were many theaters near the restaurant, and I often got free tickets at the local public bath. Not having much money, I was very grateful for those tickets. I loved movies like A Man from Abashiri Prison starring Ken Takakura. Afterward, I would eat at a nearby cafeteria and then go home to sleep. That was the kind of life I led.

STICKING IT OUT MADE ME WHAT I AM TODAY

Live-in apprentices were guaranteed one thing only: a room. Initially, my wages were so low that I couldn’t even buy myself a knife. I was dying to have one of my own, and a senior coworker gave me one of his that was broken. “Here,” he said. “If you can fix it, it’s yours.”

I wasn’t about to pass up this opportunity. I had some experience sharpening chisels and planes in the workshop at my family’s business, and so I took it apart, then sharpened and reconstructed it. When I was done, I showed it to my coworker. “I did it!” I announced.

He took the knife and just said, “Thanks.”

I wanted to accuse him of breaking his word, but the pecking order in the restaurant business was very strict, and I had to take it without complaining. This incident, however, fueled my fighting spirit, and I was determined to show him up by becoming better than him at whatever I did.

I also had to endure being on probation. As a minor who had caused a serious accident, I was required to visit the probation officer once a month until the age of twenty to have my probation book stamped. My boss and his wife, both of whom knew this, would give me permission to leave work early whenever the day for my visit came around. I walked the few blocks from our restaurant to the probation officer’s house. My probation officer was a woman named Mrs. Yamada, and I had to report to her what I had done during the last month and have her stamp my book. I was still feeling defiant, and that probably showed in my attitude. Sometimes she would pop by the restaurant and look inside on her way somewhere. I could feel her eyes on me, and it hurt my pride to be under constant supervision. Although it was my own fault, I still found this hard to bear. Looking back on it, I’m just glad that I didn’t give up.

I was so intent on proving to those who “spied” on me that they were wrong that I showed up faithfully every month to have my book stamped. These efforts were rewarded. My probation, which should have lasted until I reached maturity, was terminated after just one year. I was told that I didn’t need to come anymore and given a necktie, five 100-yen coins, and a certificate. I shredded the certificate as well as the stamp book that I had used for the last year and slashed the tie into pieces with a pair of scissors. That’s how immature I was, even though I was an apprentice sushi chef taking my first steps toward my goal.

But those years of persevering at the bottom of the pecking order and enduring the humiliation of constant supervision were a priceless period in my life. I had announced to one and all that I would become a sushi chef, and if I gave up, I would look like a fool. This knowledge drove me on. Having been expelled from school, nothing was going to make me deviate from this path, regardless of any wounds to my self-esteem. That, I think, is why I was able to stick it out to the end. To lose my temper would have meant the end of everything.

WORK FOR A FINE PERSON, NOT FOR A FINE SHOP

I later learned that if I had worked for a larger restaurant, I could have lived in a nice dorm. The master of Uokou, who had introduced me to Matsuei-sushi, had connections to some famous establishments. But he had introduced me to Matsuei-sushi instead because he believed that my boss’s caring attitude was more important. “The master of that restaurant is a good man,” he told me. Also, being as young as I was, I am not sure that I would have thrown myself so single-mindedly into my work if I had lived in a dorm with a lot of people my own age.

My mother must have been far more reassured to know that I was working for a “fine man” rather than for a “fine shop.” I now know that the character of the people who work at a restaurant is more important than its size or reputation. I would rather be known as a good man than for my restaurant to be known for making money. Even so, my mother must have been terribly worried. Yet she never stopped believing in me. This motivated me to keep on trying. When a child knows that his parent believes in him, he simply cannot betray that trust. Trust, not doubt. That, I believe, is the foundation of the bond between parent and child, as well as that between master and apprentice.

The owner of Matsuei-sushi was certainly under no obligation to take on a young delinquent as his apprentice, yet he believed in me and gave me a chance. I could not waste that opportunity. Once, I was sharpening a knife while watching TV and cut my finger so deeply that I still bear the scar to this day. I had failed to take that knife seriously. My boss was furious. “A knife is a weapon!” he shouted. “You could kill someone with it. Keep that in mind when you grip a knife in your hand, and give it your full attention.” He drilled that lesson into me. Although he was very strict, he taught me the attitude appropriate to a professional who wields a knife.

AIM HIGH AND YOU WILL GROW

About three years after I started working at Matsuei-sushi, the coworker who had broken his promise to give me his knife quit, and I was promoted to the position of oimawashi, which meant that I now assisted the other coworker in his work as sushi chef. He would tell me to do this or that, and by following his instructions, I finally started learning how to do things. This made me very happy, because that was still the era when apprentices were expected to learn just by watching.

As I gradually became more capable, I was entrusted with more work; only small jobs, though, such as making norimaki rolls or inarizushi for people to take home. I had also managed to save some money despite my low wages because I spent very little with only two days off a month. A few years after I started my apprenticeship, Matsuei-sushi began closing for two days in a row every other month. I used these holidays as opportunities to travel with my best friend from high school, Kiyoshi Sakai. Sometimes we would take his older sister and my mother with us. We went all over to places like Kyushu or Hachijo-jima, an island far south of Tokyo.

One day I overheard a customer talking about a kappo counter restaurant in Kyoto. For Japanese chefs, Kyoto is a very special place with its own unique food culture and traditions, and the kappo counter represents the height of this cuisine, with master chefs preparing seasonal dishes from the freshest ingredients right in front of their customers. The cuisine features varieties of fish that we never use in sushi, such as hamo (pike conger) and okoze (scorpion fish). The customer described dishes I had never eaten or even seen before, such as kabura mushi (grated Japanese turnip steamed with fish), amadai no sakamushi (tilefish steamed with sake), clear clam soup, and ginger rice. I decided that I just had to taste these things for myself.

Once again, my friend Sakai accompanied me. In Japan, you can’t just walk into a restaurant like this off the street. You need an introduction, so I asked the guest at Matsuei-sushi to make us a reservation. Sakai and I were barely more than twenty, and I’m sure people must have wondered what youngsters like us were doing there. For our part, we came expecting to spend the better part of our scanty wages, and this made us pretty nervous. What would we do if we couldn’t pay for it all? Still, nothing could compare to the thrill we experienced when served exotic dishes we’d never seen before. After that, I saved my money and returned many times.

This kind of study could only be done by experiencing the food with my own palate. Although these frequent food-tasting trips required what for me was a huge sum of money, the purpose was not simply to eat good food, but to gain priceless experience. From the local Kyoto cuisine, I learned such valuable lessons as the flavor of Japanese soup stock and how to use tofu, yuba (bean curd sheet), seasonal vegetables, and other ingredients that aren’t used in sushi. To gain this experience, I had to push the limits of my capacity, but those lessons form the foundation that allows me to make Japanese cuisine other than sushi. Aiming high and paying for it from my own pocket kept me on my toes and motivated me to absorb everything I could.

There are many excellent restaurants all over the world now, and I constantly remind the staff of every Nobu that experience is the best teacher. “Off you go and spend your money,” I tell them.

THE SEARCH FOR GOOD FOOD LEADS ME TO MY FUTURE WIFE

Sakai was a very good friend. He joined me in my kappo counter trips to Kyoto, even though he was involved in construction, not in the restaurant business. He had always been a top student, whereas I had always been at the bottom of the class. The only certificate I ever received in elementary school was for “good health.” And, of course, I had been expelled from high school. Yet for some reason, we got along really well. He was just a great guy.

The Osaka World Expo was held in 1970. Sakai and I decided to go and hopped on a bullet train bound for Osaka. When we saw the hordes of people headed to the same place, however, we got cold feet and decided to carry on past Osaka to Kurashiki in Okayama. There, we dropped in on Shin’ichiro Fujita, the director of the Ohara Museum of Art, who was a frequent guest at Matsuei-sushi. When he saw us, he called up a restaurant named Takoshin.

“There’s a young sushi chef visiting from Tokyo,” we overheard him say. “Please feed him and his friend as much as they can eat.”

Sakai and I looked at each other and whispered, “All right!”

The food at Takoshin was so delicious that we went there for lunch the next day as well. Of course, the second time we paid for our own meal. Even though it was only lunch, it was shockingly expensive, and we felt guilty just thinking about how much Mr. Fujita must have paid for our dinner the night before. That evening we stayed at an inn called Tsurugata, again at Mr. Fujita’s introduction. It was there that I met Yoko, the woman who would become my wife. At the time, however, we didn’t speak to each other or feel any tug of destiny.

About a year later, Mr. Fujita dropped into Matsuei-sushi when he was visiting Tokyo. With him, he brought Yoko. He had gotten her a job working in the cloakroom of a restaurant in Shiba, Tokyo, and had invited her to come with him. He pointed out to us that we had met the previous year at the inn in Kurashiki, and, although neither of us remembered the other at all, we politely said, “Oh, yes, now that you mention it.”

In that era, sushi chefs in Japan were often treated as mavericks, and girls certainly didn’t view them as desirable marriage partners. With only two days off a month, I had no time to date a girl anyway. But somehow I felt we were a match. The fact that she was older than me actually made me feel more comfortable. We began dating and were married the following year. I was just twenty-three, and she was one year older.

TRYING OUT NEW DISHES WHEN THE BOSS WASN’T LOOKING

Around the same time, the senior coworker who I had been working under opened his own restaurant, and I became senior sushi chef at Matsuei-sushi. The boss left most of the work to me, and, although perhaps I shouldn’t boast, many of the guests had become my fans.

There were many bars and restaurants in that area of Shinjuku, and Matsuei-sushi’s regulars often visited several establishments in a single night. Occasionally, someone might arrive quite drunk after closing and demand a drink. Because I was live-in staff, I would come out right away to let them in and prepare them a snack and a drink. Having watched the way my boss treated his customers, I think I just automatically assumed I should do my best to fulfill their requests, regardless of how unreasonable they might be. They affectionately called me “Matchan” and would stop by casually for a drink and a bite when pub-hopping. Some of those who woke me up after hours are now regular guests at Nobu Tokyo. They were not just my seniors in age but also in experience, and as they were active on the world stage, the tales with which they entertained me greatly influenced my life.

Once my boss began leaving things more up to me, I was no longer satisfied just to make what people ordered. The desire to experiment with new ideas surged inside me. For example, I was one of the first to serve sardine and Pacific saury as sashimi at a time when few chefs served these fish raw. In summer, I purchased fresh sea bass and served it as arai (thin slices in ice water) or as nikogori (jellied fish) to accompany drinks. Wanting to try my hand at some of the kappo dishes I had eaten in Kyoto, I sometimes bought fish without asking my boss for permission. When he happened to find out, he would grumble about my unnecessary expenditures.

THE ORIGIN OF MY PHILOSOPHY “PUT YOUR HEART INTO YOUR WORK AND COOK WITH PASSION”

Of course, whenever I made something new, I would recommend it to whoever was there. Matsuei-sushi guests were all quite wealthy and well established in their fields, and I’m sure that the dishes I was capable of producing would have been nothing new to them. But to me, they were my creations. I really wanted people to try them, and my guests must have sensed my enthusiasm because they all urged me to go ahead and serve what I had made.

I was always trying to imagine how each guest would respond to a new dish. My longing to see delight on their faces seemed to spark one idea after another. All my thoughts were focused on how to make them happy. I planned what to say when recommending a new dish, how to present it and how to explain it. This enthusiasm was infectious, and my guests responded in kind. I think that this was the origin of my philosophy “Put your heart into your work and cook with passion.” In particular, I think that this experience of preparing food for my guests while watching their reactions across the counter inspired the very popular Chef’s Omakase course at my first restaurant, Matsuhisa.

I was just a simple-hearted sushi chef who loved his work. The customers treated me with good-humored affection, perhaps because they liked my attitude and thought I was an interesting young man. The well-known interior designer Tadashi Akiyama, in particular, taught me many things.

Once, however, I went too far. Keisuke Serizawa, the famous textile designer, was at the counter, and in my eagerness, I kept pressing him to try one new dish after another. “Let me eat what I want!” he finally exclaimed.

Although some customers could be a bit demanding, I never lost my temper. I loved listening to them, and, as I was young, I could listen without bias to anything they had to share. I often asked them questions and soaked up their answers like a sponge. If they said, “Give me another drink,” I said, “Yes, sir,” and if they said, “You want one, too?” I said, “Yes, sir.” Being young has its advantages.

With Mr. Akiyama.

AN OFFER TO START A SUSHI RESTAURANT IN PERU

I think it was right around the time Yoko and I were talking about getting married that Luis Matsufuji began frequenting Matsuei-sushi. A second-generation Japanese-Peruvian, Luis was a prominent businessman whose parents had made it rich growing black pepper in Peru. Probably everyone in the capital of Lima knew his name. He was a dynamic person who went fishing on the Amazon with the well-known Japanese novelist Takeshi Kaiko.

When he came to Matsuei-sushi, he would sit at the counter and tell me stories of Peru. Before I knew it, the picture he painted of the Amazon overlapped with my image of my father in Palau. Because he was so dynamic, I found his stories captivating. Spurred on by my enthusiastic response, he would become even more animated. He became one of my fans, and we hit it off well. One day he said, “You should come to Peru. We’ll start up a sushi restaurant together.”

Here was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to fulfill both of my dreams simultaneously: to be a sushi chef and to work overseas. I knew immediately that that was what I wanted to do. But I owed Matsuei-sushi a lot. My boss had literally been like a father to me. I had even asked him to serve as the nakodo (ceremonial matchmaker) at our wedding, a role as important as best man. How could I ask him to let me go to Peru? I agonized over this for some time. When I finally made up my mind and consulted him, he suggested that I go and see what it was like first. And that was how I ended up going alone to Peru to investigate.

It was my first trip overseas ever. But as my image of “going overseas” was not going to New York or London but to “primitive lands” like my father, Peru fit my image perfectly. On my first visit, the country seemed backward. There were only three or four Japanese restaurants in Lima at that time. Having come all this way, I wanted to see what working there might be like and spent a few days working at a restaurant called Tokyo Sushi. Although they told me many things, my skills were frankly superior. Despite the fact that the fish varieties used were unfamiliar, I was confident I could prepare them better.

Yoko and I decided to move to Peru after our wedding. But when my mother heard this, she rushed over to our apartment and, falling to her knees, grabbed my legs and burst into tears. “Please don’t go!” she begged. Before World War II, many Japanese had immigrated to Peru, but quite a number of families that had boarded ships bound for South America never returned to Japan. Having heard such stories, my mother must have been worried that she would never see us again. I explained that times had changed. Far from being a frontier land, Peru could now be reached by plane, and we would not be gone for life. In the end, I managed to convince her to let us go.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria/Emily Bestler Books (November 1, 2019)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501122804

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"The secret to the appeal of this charming memoir resides in Matsuhisa's personal simplicity . . . A straightforward memoir sure to please both Nobu fans and Japanese cuisine lovers."

– Kirkus Reviews

"More than a culinary-centric memoir, the book carries the wisdom of a successful self-made man who made many mistakes and who had weaknesses and moments of despair . . . relatable life lessons from a passionate spirit are what keep the pages turning."

– Eater, The Best Food-Focused Memoirs of Fall 2017

"An insightful peek into the mind of one of the world's most successful restaurateurs."

– Library Journal

"Sweet, charming, experienced, and humble, a world-famous chef reveals the experiences that helped shape him and his thinking, and imparts meaning."

– What's Nonfiction? Blog

"Nobu is one of the good guys who has become famous by the old-fashioned tenets of being a family man, hard work, passion, and perseverance even in the face of adversity . . . This is inspiration by example."

– The Associated Press

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Nobu Trade Paperback 9781501122804