Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

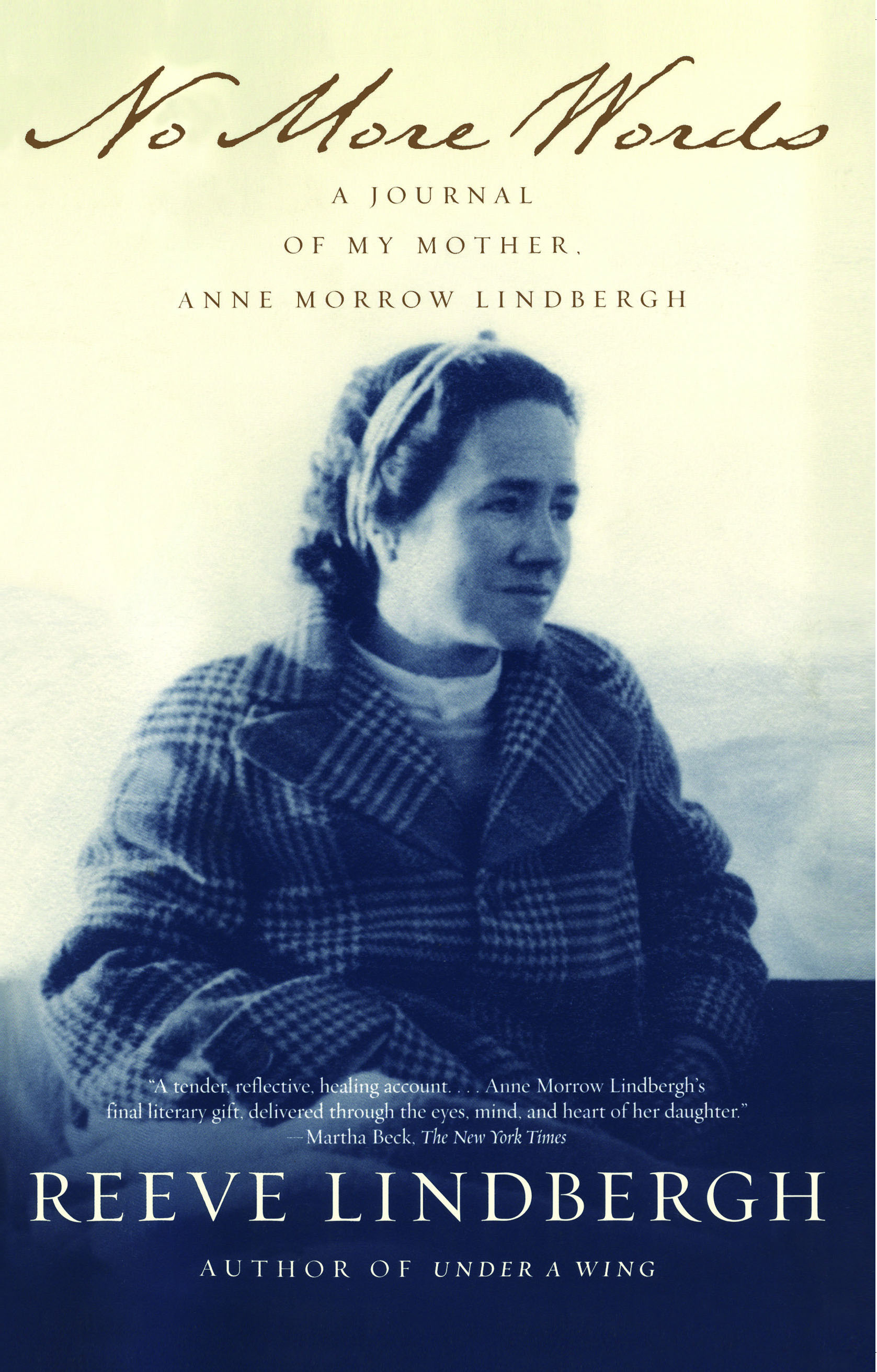

About The Book

In 1999 Anne Morrow Lindbergh, the famed aviator and author, moved from her home in Connecticut to the farm in Vermont where her daughter, Reeve, and Reeve's family live. Mrs. Lindbergh was in her nineties and had been rendered nearly speechless years earlier by a series of small strokes that also left her frail and dependent on others for her care. As an accomplished author who had learned to write in part by reading her mother's many books, Reeve was deeply saddened and frustrated by her inability to communicate with her mother, a woman long recognized in her family and throughout the world as a gifted communicator.

No More Words is a moving and compassionate memoir of the final seventeen months of Reeve's mother's life. Reeve writes with great sensitivity and sympathy for her mother's plight, while also analyzing her own conflicting feelings. Anyone who has had to care for an elderly parent disabled by Alzheimer's or stroke will understand immediately the heartache and anguish Reeve suffered and will find comfort in her story.

No More Words is a moving and compassionate memoir of the final seventeen months of Reeve's mother's life. Reeve writes with great sensitivity and sympathy for her mother's plight, while also analyzing her own conflicting feelings. Anyone who has had to care for an elderly parent disabled by Alzheimer's or stroke will understand immediately the heartache and anguish Reeve suffered and will find comfort in her story.

Excerpt

Chapter One: September 1999

I learned to know the world through words, but they were not my own. From the beginning of my life, as I remember it, everything I understood was made plain to me in her language, which I knew much better than my own. Her quiet voice, her exquisite gentle articulation, her loving eloquence, all of these things spoke me through my days, comforted my nights, and gave each hour of every twenty-four its substance, shape, and meaning from the time that I was born.

She knew me well, and at each moment of my need, she spoke the words I needed. Sometimes the words were abstract, the language vague, but the message was always uncannily the right one for that instant. When I was a child -- the youngest of her five offspring -- and injured or unhappy, she would say, "Everybody loves you, Reeve!" and that was enough to draw the healing circle of affection around me and mend my trouble, whether it was a skinned knee or a bruised heart.

When I was grown and had my own daughter, and reveled in the ecstatic connection between me as nursing mother and my baby at my breast, my mother watched us and told me, "It is, of course, the only perfect human relationship." This made me laugh, but at the same time, I believed her. I still do.

Then later, when I lost my first son just before his second birthday, she who had also lost her first son knew what to say, and she was one of the few people I was willing to listen to. She told me the truth first. After I had found my baby's dead body one January morning, just after it was taken away but before the family had gathered together in shock and bewilderment to comfort one another, my mother said, "This horror will fade, I can promise you that. The horror fades. The sadness, though, is different. The sadness remains..."

That, too, was correct. The horror faded. I left it behind me in that terrible winter, but the sadness remained. Gradually, over the years, it became a member of my family, like our old dog sleeping in the corners. I got used to my sadness, and I developed a kind of affection for it. I still have conversations with it on cloudy days. Come here, sadness, I say, come sit with me and keep me company. We've known each other for a long time, and we have nothing to fear from each other. But my mother was right. It does remain.

At the time of my son's death, when I asked my mother what would happen to me as the mother of the child, how that part of me would continue, she said, "It doesn't. You die, that's all. That part of you dies with him. And then, amazingly, you are reborn."

At the time, it was very hard to believe the last part of what she said, although I understood the dying part. It felt that way, certainly. I did not expect to feel any other way, ever again. But she was right again. I died with my first son, and then later, never thinking it could happen, I was reborn into a whole different life with my second.

Sometimes I still hear my mother's voice in my head, telling me that all is well, that the logic of existence is intact -- not painless but intact and, in its own way, beautiful -- and that she is still here.

In fact, she is still here. And she speaks on rare occasions, but not in the clear, quiet voice I used to know so well, inhabited by a meaning intended, as I always believed, just for me. One of my mother's great gifts with language was that each person who listened to her, like each person who read her books, believed that she was talking intimately and exclusively to him or her.

Age and illness have silenced her now, and she lives in silence to such a degree that speech, when it does come, seems unfamiliar to her, her voice hoarse and thick with the difficulty brought on by disuse, a rustiness of pipes and joints too long unlubricated by their once normal flow. She speaks to make a discomfort known, perhaps -- "I'm cold" -- or to ask an idle question: "Is someone in the kitchen?" "What are you reading?"

Reading. There it is. Reading. That's where I have learned to look for her lately. That's where she is. That is where she lives now. Reading. I am just beginning to understand, and my understanding excites me in the way an explorer must feel when coming to the top of what seemed an impenetrable mountain, treeless with rocky escarpments and no view, and suddenly, without warning or expectation, sees a whole new country beyond...fields, forest, a river that was not on any map.

She once conversed and kept silence only briefly, as an emphasis in conversation. Silence for her was like a rest in music: a pause with a point. She would stop talking, then sigh, then look me in the eye or glance briefly, mysteriously away. Then she would say something that would make me laugh, or that I would write down to treasure always:

"Grandmothers are either tired...or lonely!" "The cure for loneliness is solitude." (I am just beginning to understand what this means.)

Later, poignantly, after my father -- along with most of the men of his generation -- had passed away, she would tell me, "Grandchildren are the love affair of old age." When we asked a friend to design and paint a toy chest for the grandchildren who visited her, we had that aphorism painted on the side of it.

Now, instead of conversing, she reads. She reads almost constantly, unless she is sleeping, or eating, or watching a video on television in the evening. She often reads without interruption; even when company is in the room, she does not look up from the book, sometimes for hours.

She reads while sitting in the armchair in her living room, from any one of a pile of books neatly stacked on the table in front of her, near the vase of flowers, and the collection of smooth stones, a seashell or two, and one stuffed plush robin that was given to her as a party favor at a grandson's birthday in July. It's a Beanie Baby, I notice.

"I love him very much," she says to me, when I pick up and hold the stuffed bird for a moment, admiring his puffed-out red breast and the brightness of the two plastic yellow-and-black beads that are his eyes. Does she remember the party? Does she remember the grandson? (The last time my brother Land called, when I was sitting with her, she told him, "I'm here with my sister," and looked over pleasantly at me.)

I don't know what she remembers, and I finally have learned not to ask. In any case, it would be rude to interrupt her. She is reading.

Sometimes, if I am with her for several hours and she leaves the room to take a nap or to use the bathroom, I look through the pile on her table to see which books she has chosen for the week. The first time I did this, I almost laughed out loud -- not at the reading material, but at my own surprise.

These were the same books, or at least the same authors, I had seen for forty-five years on her tables and shelves. There were even some of the same titles I had memorized as a child, without understanding their meaning, when I lay on the bed in her room early in the morning, after having crept into

bed with my parents in the middle of the night because of a bad dream, or a sudden noise outside, or simply because I had fallen into one of the unnameable bottomless crevasses of fear and loneliness in which some children find themselves when there is darkness everywhere.

Here they were all over again: The Divine Milieu by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin; Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot; Rainer Maria Rilke's Duino Elegies. I remembered these all so well. I remembered, too, as I looked at the Duino Elegies how many years it took before I could appreciate Rilke, despite having been introduced to his books on my mother's shelves almost before I could read. The air was so thin as to be almost unbreathable, it seemed to me, in the intellectual and poetic atmosphere in which this man lived and thought. His literary and poetic presence was so ethereal, so romantic, that I couldn't imagine him in the flesh and could not picture him with any physical body at all.

As a teenager, I was taken by my mother, who adored Rilke, to the church where he was buried in a village in the Rhone Valley in Switzerland. There I was told that the poet had died from an infection caused, my mother told me in a voice hushed with awe and sorrow, "from the prick of a rose..." All I could do at the time was nod respectfully, but inside I was muttering to myself, Give me a break!

I came to love Rilke despite his lofty aesthetics, and I should not have been surprised to see him so well represented in my mother's daily readings. Why was I so surprised? Was it that her reading sophistication was so much more elevated than her conversation level? Isn't that true for all of us? Most people can read much more profoundly than they can write, speak, or even think. For me, this is one of the great humiliations of being literate at all. If I can read Shakespeare, why can't I write Shakespeare? It's not fair.

I suppose I am surprised that my mother's ability to read and think has not been taken from her, while the ability to use what she is reading and thinking clearly has. Or has it?

I make so many assumptions in my love for this person who is very old and very quiet. Desperate for communication, equally desperate for some kind of certainty in the bafflement and enigma that her old age has presented, I hang on every one of the few words my mother utters. I decide at certain moments that my aging parent has always been an oracle. At other moments, depressed and discouraged, I think she must have become an idiot.

I rediscovered a printed copy of a speech she delivered in New York City in 1981, about aging (she was then seventy-five), and I found it so moving that I brought it to show her last week, and to read it aloud, in the evening. She had spoken to a group of women at the Cosmopolitan Club about the inevitability of moving from stage to stage in one's life, and the need to welcome each stage with a different readiness while learning from the movement itself. She likened the process to a game of musical chairs, and she quoted Simone Weil, T. S. Eliot, Bernard Baruch, and others. At the end of the speech she read from one of Eliot's Four Quartets, "Dry Salvages," finishing with these words:

The moments of happiness -- not the sense of well-being,

Fruition, fulfillment, security or affection,

Or even a very good dinner, but the sudden illumination --

We had the experience but missed the meaning,

And approach to the meaning restores the experience

In a different form, beyond any meaning

We can assign to happiness.

My mother's caregivers loved the speech as much as I did.

"Thank you, Mrs. Lindbergh," someone said into the quiet after I finished reading. "Those are wonderful words."

"Aren't they?" I said. I was pleased and turned to my mother in her chair. "It is such a beautiful speech -- so much insight, so much humor. It's a gift!"

But my mother was looking at me with an intensity that I had misinterpreted. She had looked this way all through my reading, and I had thought it was a listener's intensity. Instead it was internal preoccupation, something with too much force of its own to allow her to hear anything else. "Take me!" she said. "Take me away! They spank children here!"

I don't think there was a pause. We all reassured her at once. Nobody would spank her, nobody spanked anybody here.

"I don't allow spanking on my farm!" I said with a smile. We all talked about spanking among ourselves -- all except my mother, who had fallen silent once more. I recalled, to the room in general, my mother's fear of one grim childhood nanny. Had she been spanked far, far in the past? It must have been awful.

"They spank children!" my mother said several times, as if she hadn't heard the conversation at all. We continued to reassure her until finally she said to me, as if weary of the whole topic, and of me and my lack of comprehension, "Please -- go." It was late, and I went.

Into the pool of mystery -- which frightens me -- leaps a whole team of explanations, like lifeguards, busily rescuing me with their practiced phrases: "She doesn't understand what she's saying...This can't mean anything. It's just nonsense." Or, conversely, "What is she trying to say? It must mean something very important. I must try to understand. What's wrong with me, that I don't understand?"

Conversation was so integral to my own sense of my mother's life and identity that I cannot accept its absence. I find myself inventing her speech when I am with her, and continuing with the invention long afterward. Now my mother's eloquence has found new life in my mind, and in my dreams.

Copyright © 2001 by Reeve Lindbergh

I learned to know the world through words, but they were not my own. From the beginning of my life, as I remember it, everything I understood was made plain to me in her language, which I knew much better than my own. Her quiet voice, her exquisite gentle articulation, her loving eloquence, all of these things spoke me through my days, comforted my nights, and gave each hour of every twenty-four its substance, shape, and meaning from the time that I was born.

She knew me well, and at each moment of my need, she spoke the words I needed. Sometimes the words were abstract, the language vague, but the message was always uncannily the right one for that instant. When I was a child -- the youngest of her five offspring -- and injured or unhappy, she would say, "Everybody loves you, Reeve!" and that was enough to draw the healing circle of affection around me and mend my trouble, whether it was a skinned knee or a bruised heart.

When I was grown and had my own daughter, and reveled in the ecstatic connection between me as nursing mother and my baby at my breast, my mother watched us and told me, "It is, of course, the only perfect human relationship." This made me laugh, but at the same time, I believed her. I still do.

Then later, when I lost my first son just before his second birthday, she who had also lost her first son knew what to say, and she was one of the few people I was willing to listen to. She told me the truth first. After I had found my baby's dead body one January morning, just after it was taken away but before the family had gathered together in shock and bewilderment to comfort one another, my mother said, "This horror will fade, I can promise you that. The horror fades. The sadness, though, is different. The sadness remains..."

That, too, was correct. The horror faded. I left it behind me in that terrible winter, but the sadness remained. Gradually, over the years, it became a member of my family, like our old dog sleeping in the corners. I got used to my sadness, and I developed a kind of affection for it. I still have conversations with it on cloudy days. Come here, sadness, I say, come sit with me and keep me company. We've known each other for a long time, and we have nothing to fear from each other. But my mother was right. It does remain.

At the time of my son's death, when I asked my mother what would happen to me as the mother of the child, how that part of me would continue, she said, "It doesn't. You die, that's all. That part of you dies with him. And then, amazingly, you are reborn."

At the time, it was very hard to believe the last part of what she said, although I understood the dying part. It felt that way, certainly. I did not expect to feel any other way, ever again. But she was right again. I died with my first son, and then later, never thinking it could happen, I was reborn into a whole different life with my second.

Sometimes I still hear my mother's voice in my head, telling me that all is well, that the logic of existence is intact -- not painless but intact and, in its own way, beautiful -- and that she is still here.

In fact, she is still here. And she speaks on rare occasions, but not in the clear, quiet voice I used to know so well, inhabited by a meaning intended, as I always believed, just for me. One of my mother's great gifts with language was that each person who listened to her, like each person who read her books, believed that she was talking intimately and exclusively to him or her.

Age and illness have silenced her now, and she lives in silence to such a degree that speech, when it does come, seems unfamiliar to her, her voice hoarse and thick with the difficulty brought on by disuse, a rustiness of pipes and joints too long unlubricated by their once normal flow. She speaks to make a discomfort known, perhaps -- "I'm cold" -- or to ask an idle question: "Is someone in the kitchen?" "What are you reading?"

Reading. There it is. Reading. That's where I have learned to look for her lately. That's where she is. That is where she lives now. Reading. I am just beginning to understand, and my understanding excites me in the way an explorer must feel when coming to the top of what seemed an impenetrable mountain, treeless with rocky escarpments and no view, and suddenly, without warning or expectation, sees a whole new country beyond...fields, forest, a river that was not on any map.

She once conversed and kept silence only briefly, as an emphasis in conversation. Silence for her was like a rest in music: a pause with a point. She would stop talking, then sigh, then look me in the eye or glance briefly, mysteriously away. Then she would say something that would make me laugh, or that I would write down to treasure always:

"Grandmothers are either tired...or lonely!" "The cure for loneliness is solitude." (I am just beginning to understand what this means.)

Later, poignantly, after my father -- along with most of the men of his generation -- had passed away, she would tell me, "Grandchildren are the love affair of old age." When we asked a friend to design and paint a toy chest for the grandchildren who visited her, we had that aphorism painted on the side of it.

Now, instead of conversing, she reads. She reads almost constantly, unless she is sleeping, or eating, or watching a video on television in the evening. She often reads without interruption; even when company is in the room, she does not look up from the book, sometimes for hours.

She reads while sitting in the armchair in her living room, from any one of a pile of books neatly stacked on the table in front of her, near the vase of flowers, and the collection of smooth stones, a seashell or two, and one stuffed plush robin that was given to her as a party favor at a grandson's birthday in July. It's a Beanie Baby, I notice.

"I love him very much," she says to me, when I pick up and hold the stuffed bird for a moment, admiring his puffed-out red breast and the brightness of the two plastic yellow-and-black beads that are his eyes. Does she remember the party? Does she remember the grandson? (The last time my brother Land called, when I was sitting with her, she told him, "I'm here with my sister," and looked over pleasantly at me.)

I don't know what she remembers, and I finally have learned not to ask. In any case, it would be rude to interrupt her. She is reading.

Sometimes, if I am with her for several hours and she leaves the room to take a nap or to use the bathroom, I look through the pile on her table to see which books she has chosen for the week. The first time I did this, I almost laughed out loud -- not at the reading material, but at my own surprise.

These were the same books, or at least the same authors, I had seen for forty-five years on her tables and shelves. There were even some of the same titles I had memorized as a child, without understanding their meaning, when I lay on the bed in her room early in the morning, after having crept into

bed with my parents in the middle of the night because of a bad dream, or a sudden noise outside, or simply because I had fallen into one of the unnameable bottomless crevasses of fear and loneliness in which some children find themselves when there is darkness everywhere.

Here they were all over again: The Divine Milieu by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin; Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot; Rainer Maria Rilke's Duino Elegies. I remembered these all so well. I remembered, too, as I looked at the Duino Elegies how many years it took before I could appreciate Rilke, despite having been introduced to his books on my mother's shelves almost before I could read. The air was so thin as to be almost unbreathable, it seemed to me, in the intellectual and poetic atmosphere in which this man lived and thought. His literary and poetic presence was so ethereal, so romantic, that I couldn't imagine him in the flesh and could not picture him with any physical body at all.

As a teenager, I was taken by my mother, who adored Rilke, to the church where he was buried in a village in the Rhone Valley in Switzerland. There I was told that the poet had died from an infection caused, my mother told me in a voice hushed with awe and sorrow, "from the prick of a rose..." All I could do at the time was nod respectfully, but inside I was muttering to myself, Give me a break!

I came to love Rilke despite his lofty aesthetics, and I should not have been surprised to see him so well represented in my mother's daily readings. Why was I so surprised? Was it that her reading sophistication was so much more elevated than her conversation level? Isn't that true for all of us? Most people can read much more profoundly than they can write, speak, or even think. For me, this is one of the great humiliations of being literate at all. If I can read Shakespeare, why can't I write Shakespeare? It's not fair.

I suppose I am surprised that my mother's ability to read and think has not been taken from her, while the ability to use what she is reading and thinking clearly has. Or has it?

I make so many assumptions in my love for this person who is very old and very quiet. Desperate for communication, equally desperate for some kind of certainty in the bafflement and enigma that her old age has presented, I hang on every one of the few words my mother utters. I decide at certain moments that my aging parent has always been an oracle. At other moments, depressed and discouraged, I think she must have become an idiot.

I rediscovered a printed copy of a speech she delivered in New York City in 1981, about aging (she was then seventy-five), and I found it so moving that I brought it to show her last week, and to read it aloud, in the evening. She had spoken to a group of women at the Cosmopolitan Club about the inevitability of moving from stage to stage in one's life, and the need to welcome each stage with a different readiness while learning from the movement itself. She likened the process to a game of musical chairs, and she quoted Simone Weil, T. S. Eliot, Bernard Baruch, and others. At the end of the speech she read from one of Eliot's Four Quartets, "Dry Salvages," finishing with these words:

The moments of happiness -- not the sense of well-being,

Fruition, fulfillment, security or affection,

Or even a very good dinner, but the sudden illumination --

We had the experience but missed the meaning,

And approach to the meaning restores the experience

In a different form, beyond any meaning

We can assign to happiness.

My mother's caregivers loved the speech as much as I did.

"Thank you, Mrs. Lindbergh," someone said into the quiet after I finished reading. "Those are wonderful words."

"Aren't they?" I said. I was pleased and turned to my mother in her chair. "It is such a beautiful speech -- so much insight, so much humor. It's a gift!"

But my mother was looking at me with an intensity that I had misinterpreted. She had looked this way all through my reading, and I had thought it was a listener's intensity. Instead it was internal preoccupation, something with too much force of its own to allow her to hear anything else. "Take me!" she said. "Take me away! They spank children here!"

I don't think there was a pause. We all reassured her at once. Nobody would spank her, nobody spanked anybody here.

"I don't allow spanking on my farm!" I said with a smile. We all talked about spanking among ourselves -- all except my mother, who had fallen silent once more. I recalled, to the room in general, my mother's fear of one grim childhood nanny. Had she been spanked far, far in the past? It must have been awful.

"They spank children!" my mother said several times, as if she hadn't heard the conversation at all. We continued to reassure her until finally she said to me, as if weary of the whole topic, and of me and my lack of comprehension, "Please -- go." It was late, and I went.

Into the pool of mystery -- which frightens me -- leaps a whole team of explanations, like lifeguards, busily rescuing me with their practiced phrases: "She doesn't understand what she's saying...This can't mean anything. It's just nonsense." Or, conversely, "What is she trying to say? It must mean something very important. I must try to understand. What's wrong with me, that I don't understand?"

Conversation was so integral to my own sense of my mother's life and identity that I cannot accept its absence. I find myself inventing her speech when I am with her, and continuing with the invention long afterward. Now my mother's eloquence has found new life in my mind, and in my dreams.

Copyright © 2001 by Reeve Lindbergh

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (December 15, 2002)

- Length: 176 pages

- ISBN13: 9780743203142

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

Nancy Jacobsen Rocky Mountain News Lindbergh's youngest daughter delves into her mother's final two years, detailing the poignant, melancholic, and sometimes humorous emotions she felt while caring for the elderly woman....A loving tribute to mother, author, and woman.

Meg Laughlin The Miami Herald Intimate [and] down-to-earth...funny and engaging...honest.

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): No More Words Trade Paperback 9780743203142(0.6 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Reeve Lindbergh Photo Credit:(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit