Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

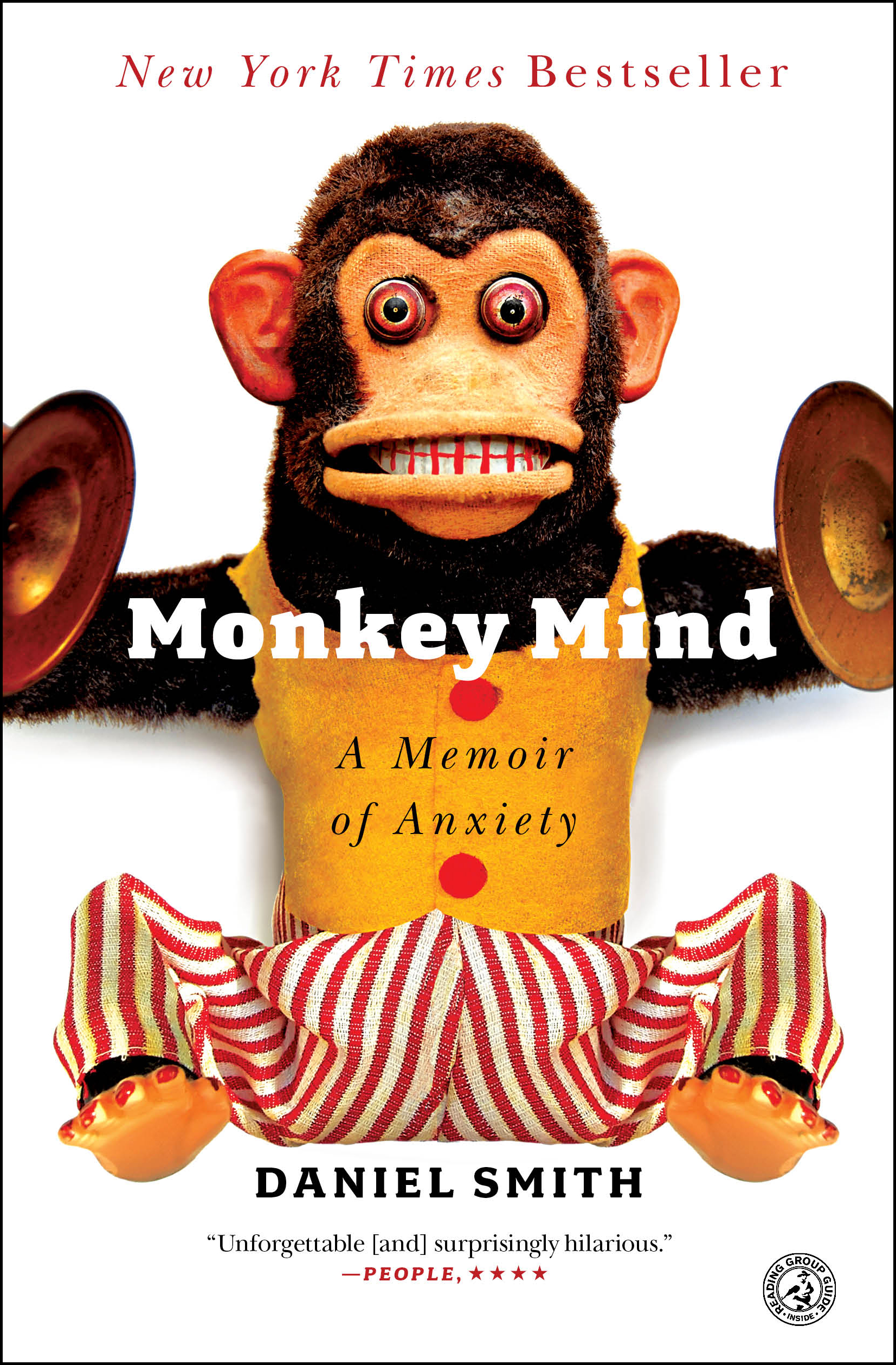

About The Book

Daniel Smith’s Monkey Mind is the stunning articulation of what it is like to live with anxiety. As he travels through anxiety’s demonic layers, Smith defangs the disorder with great humor and evocatively expresses its self-destructive absurdities and painful internal coherence. Aaron Beck, the most influential doctor in modern psychotherapy, says that “Monkey Mind does for anxiety what William Styron’s Darkness Visible did for depression.” Neurologist and bestselling writer Oliver Sacks says, “I read Monkey Mind with admiration for its bravery and clarity. . . . I broke out into explosive laughter again and again.” Here, finally, comes relief and recognition to all those who want someone to put what they feel, or what their loved ones feel, into words.

Excerpt

The story begins with two women, naked, in a living room in upstate New York.

In the living room, the blinds have been drawn. The coffee table, which is stained and littered with ashtrays, empty bottles, and a tall blue bong, has been pushed against the far wall. The couch has been unfurled. It is a cheap couch, with no springs or gears or wooden endoskeleton; its cushions unfold flat onto the floor with a flat slapping sound: thwack. Also on the floor are several clear plastic bags containing dental dams, spermicidal lubricant, and latex gloves. There is everything, it seems to me, but an oxygen tank and a gurney.

I am hunched in an awkward squat behind a woman on all fours, a woman who is blond and overweight. Her buttocks are exposed and her knees are spread wide—“presenting,” they call it in most mammalian species. I am sixteen years old. I have never before seen a vagina up close, an in-person vagina. My prior experience has been limited to two-dimensional vaginas, usually with creases and binding staples marring the view. To mark the occasion, I would like to shake the vagina’s hand, talk to it for a while. How do you do, vagina? Would you like some herbal tea? But the vagina is businesslike and gruff. An impatient vagina, a waiting vagina. A real bureaucrat of a vagina.

I inch closer on the tips of my toes, knees bent, hands out, fingers splayed—portrait of the writer as a young lecher. The air in the room smells like a combination of a women’s locker room and an off-track betting parlor, all smoke and sweat and scented lotions. My condom, the first I’ve had occasion to wear in anything other than experimental conditions, pinches and dims sensation, so that my penis feels like what I imagine a phantom limb must feel like. The second woman has brown hair done up in curls, round hips, and dark, biscuit-wide nipples. She lies on the couch, waiting. As I proceed, foot by foot, struggling to keep my erection and my balance at the same time, her eyes coax me forward. She is touching herself.

Now the target vagina is only a foot away. Now I feel like a military plane, preparing for in-air refueling. I feel, also, like a symbol. This is why I am here, ultimately. This is why, when the invitation was extended (“Do you want to stay? I want you to stay”), I accepted, and waited who knows how long in the dark room for them to return. How could I have said no? What I had been offered was every boy’s dream. Two women. The dream.

Through a haze of cannabis and cheap beer, I bolster my courage with this: the dream. What I am about to do is not for myself. It is for my people, my tribe. Dear friends, this is not my achievement. This is your achievement. Your victory. A fulfillment of your desires. Oh poor, suffering, groin-sore boys of the eleventh grade, I hereby dedicate this vagina to—

It is then that the woman coughs. It is a rattling, hacking cough. A cough of nicotine and phlegm. And the vagina, which is connected to the cough’s apparatus by some internal musculature I could not possibly have imagined before this moment, winks at me. With its wild, bushy, thorny lashes, it winks. My heart flutters. My breathing quickens. I have been winked at by a vagina that looks like Andy Rooney. I feel a tightness in my chest and I think to myself, Oh dear lord, what have I gotten myself into?

Reading Group Guide

Join our mailing list! Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Introduction

Monkey Mind is a memoir of one man’s life of anxiety and his quest to both understand and overcome it. Anxiety once paralyzed Daniel Smith, causing him to chew his cuticles until they bled. It has dogged his days, threatened his sanity, and ruined his relationships. In Monkey Mind, Smith articulates what it is like to live with anxiety, demystifying the disease with humor and evocatively expressing its self-destructive absurdities. With honesty and wit, Smith shares his own hilarious and heart-wrenching story of anxiety and how he was finally able to tame the affliction.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. Smith begins Monkey Mind with two epigraphs, one from The Woman in White that reads, in part, “We all say it’s on the nerves, and we none of us know what we mean when we say it,” and one from Nabokov’s “Signs and Symbols” that reads, “Everything is a cipher and of everything he is the theme.” Discuss both of these epigraphs within the context of Smith’s memoir. How do they set up his discussion of anxiety and inform your reading of Monkey Mind?

2. Discuss the book’s title. Why do you think that Smith chose it? What does it mean to have a “monkey mind”?

3. In the introduction to Monkey Mind, Smith says, “I was anxiety personified.” (p. 7) What do you think he means? Given what you know about Daniel at this stage of his memoir, do you agree with his self-assessment? Why or why not?

4. When Smith visits a therapist while he is in college and is asked for the reason behind his visit, he says, “I suffer from anxiety.” This is the first time that he has “said it like that before. I’d never used the word in that kind of sentence.” ( p. 129) Why do you think that Smith chooses to describe his motivation for seeking help in the way that he does? Do you think that the change in phrasing also suggests a change in the way that he views his problem? How so?

5. Smith says anxiety “is after all a relationship of a sort.” (p. 74) What do you think he means by this statement? In what ways do you see Daniel’s life dominated by anxiety? Were any of those ways surprising to you?

6. Esther plays a huge role in Daniel’s life. What are your impressions of her based on Daniel’s descriptions? Why do you think that Daniel develops a friendship with her despite his reservations? What are the results of the friendship?

7. According to Smith, “In love, anxiety takes victims.” (p. 182) How does this statement play out in regard to his relationship with Joanna? Do you see it playing out in other relationships of Daniel’s? Which ones and how?

8. Of his childhood, Smith says, “Even then it was possible that I wouldn’t become my mother.” (p. 37) Describe Marilyn. In what ways would Daniel shy away from being like her? What do you think of her ability to manage her anxiety?

9. Were you surprised that Daniel confides in his mother about his first sexual experience? Why or why not? How do each of his parents react to what he has told them?

10. According to Smith, “The truly gripping thing about anxiety had always been how physical it was.” (p. 199) Describe some of the corporeal ways in which Smith’s anxiety manifests itself. Were any particularly surprising to you? If any, which ones?

11. Daniel Smith includes a self-portrait that William James drew in his youth during a bout with anxiety and depression. (p. 119) Why do you think that Smith chose to include this image in his memoir? What does it show you about Smith’s own mental state?

12. In listing jobs that an anxiety sufferer should avoid at all costs, Smith includes “fact-checker at a major American magazine.” (p. 147) Discuss Smith’s own experiences working as a factchecker. Why does it seem to be a bad idea? Knowing what you do about anxiety after reading Monkey Mind, are there other jobs that you would add to Smith’s jobs- to-be-avoided list?

13. Although Daniel Smith sees a therapist while he is living in Boston, he says, “it wasn’t just that I was too desperate to listen to Brian. It was also that I wasn’t desperate enough.” (p. 196) What is it that eventually makes Smith more receptive to Brian’s help? How do Brian’s methods differ from those of the other therapists that Daniel has seen? What’s the result?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. Daniel Smith says, “When I found Roth, I felt I had found my anxiety’s Rosetta Stone.” (p. 136) Read one of Philip Roth’s books with your book club and discuss the role that anxiety plays. Discuss why Smith might have found Roth’s books to be a balm.

2. Smith’s in-depth article about electroshock therapy, titled “Shock and Disbelief,” which appeared in The Atlantic in 2001, was both a professional triumph and a personal disaster. Read the original article here: http://www.theatlantic.com/ magazine/archive/2001/02/shock-and-disbelief/302114/. Then, discuss the complaint against Smith.

3. To learn more about Daniel Smith, read about his other work, read reviews of Monkey Mind, and find anxiety resources, visit his official site at http://monkeymindchronicles.com.

A Conversation with Daniel Smith

1. It seems as if Monkey Mind existed in your mind for some time. What prompted you to write it? And why at this particular juncture in your career?

I was looking for something to do that had more narrative and that was more comical than my previous work, which was often journalistic and based in a lot of research. My experience with anxiety not only fit those needs perfectly, but I noticed that no one had really written a book like the one I wanted to write— one that explained, with as much sensitivity and accuracy (and necessary humor) as possible what anxiety actually feels like. I wanted to answer the question, What’s it like to go through life with a body and mind hard-wired for systemic doubt?

2. In countless consumer reviews on Goodreads, readers mention that Monkey Mind helped them understand their own anxiety or that of loved ones, and Psychology Today said, “If you’re chronically anxious and want to better explain to a loved one what you’re going through, hand them Monkey Mind.” Did you set out to write a book that would help others deal with their own anxiety?

I set out to write a book that would describe anxiety well and as an experience, not necessarily as a pathology. I think this aspect of the book is what people have responded to most and found most helpful. I’m delighted by this.

3. Writing Monkey Mind required you to revisit some of your low points in dealing with your anxiety. Was the experience therapeutic? Or did reliving some of your anxiety attacks stir up those feelings again?

There were moments when writing about my past difficulties with anxiety stirred up old worries, but these moments were surprisingly rare for the same reason, I think, that I didn’t really find any therapeutic value in the experience—because the day-to-day problems involved in writing Monkey Mind were literary and not clinical: how to tell the story well, how to describe something so elusive and complex, what to put in and what to leave out, where to put this comma or that semicolon, etc. I like to keep things separate: writing at the writing desk, therapy at the therapist’s office.

4. Aaron T. Beck praised Monkey Mind, saying it “does for anxiety what William Styron’s Darkness Visible did for depression.” Did Darkness Visible inspire you in your writing? What other books and writers influenced you?

I greatly admire Darkness Visible—it’s a powerful and vivid book—but I didn’t have it in mind as a model when I was writing Monkey Mind. Indeed, I didn’t have any models in mind. I did, however, find myself repeatedly drawn to certain works of literature. Nabokov’s marvelous short story “Signs and Symbols,” for example. For some reason I can’t explain (and don’t even really want to), I couldn’t stop reading that story. I turned to it almost daily. I also found myself turning to the biographies of great writers and thinkers who have experienced anxiety, foremost among them William James, Alice James, Kierkegaard, and Kafka.

5. Your mother was very supportive of your decision to write Monkey Mind, even when it meant that you were exposing her own dealings with anxiety. Were you surprised by her reaction?

I was and I wasn’t. On the one hand, although my mother is a psychotherapist who specializes in treating anxiety, she can be very private about her own struggles with anxiety and panic. (Perhaps her reticence is because she’s a therapist: she has to be tactful about what she does and doesn’t divulge to her patients.) On the other hand, she is a bold, brave, and unapologetic person with an almost perverse hatred of secrecy. I think she knew that the book could be useful and comforting to people, and she wanted to be part of that.

6. Many reviews have praised Monkey Mind for its humor. O Magazine said “You’ll laugh out loud many times” and, in a four star review, People calls it “unforgettable, surprisingly hilarious.” Although you are recounting your own struggles with illness, your depictions are often very funny. Was that always your intention? What did you hope to achieve by inserting comedy into your memoir?

I always knew that a book about anxiety (at least any book about anxiety that I wrote) would have to be funny. The reason for this is quite simply that anxiety is funny. It’s painful, too, of course—very painful, as well as destructive to lives in all sorts of ways. But the way anxiety causes pain and destruction is through absurdity. It inflates niggling fears and reconfigures the nervous system in a way that, even while you’re going through it, you know is overwrought. You know you’re being tricked somehow. So to write about anxiety in a comic mode (though not just in a comic mode) is a way of both acknowledging the absurdity of anxiety and of disempowering the experience just a bit. It’s a way of reasserting control for that moment of humor.

7. Your experience in the aftermath of the publication of “Shock and Disbelief” in The Atlantic was particularly harrowing, kicking off a huge anxiety attack. After that experience, have you shied away from reading reviews of your writing? How do you handle the possibility of criticism?

I haven’t shied away from reading criticism of my work, but I have learned, largely because of that episode, not to become paralyzed by criticism. There happens to be a lot you can learn from how people react to your writing; I learned a lot from how people reacted to that particular article. But you have to be selective about what criticism you deem actionable, and you always have to remember that you can’t go back. What’s published is published. All that matters is the work that’s in front of you.

8. Your initial year at Brandeis was particularly fraught and filled with severe anxiety attacks. It was also there that you first articulated that you suffered from anxiety. Following the publication of Monkey Mind, you returned to Brandeis University, this time speaking at an event co- sponsored by the Psychological Counseling Center, the creative writing department of Brandeis, and Brandeis Magazine. What was it like to return to the place you once called “the epicenter of anxiety”?

It was, remarkably, a somewhat cathartic trip. I never felt particularly comfortable or settled at Brandeis. But returning after nearly fifteen years was, to my surprise and delight, very much like coming home. There was no spasm of nerves, no reignition of old anxieties. There was just a sense of gratitude and pleasure at being back in this place I knew so well and where I learned so much. But the administration did put out baked goods at the event, so maybe that helped.

9. What has been the most rewarding aspect of publishing Monkey Mind? It has been a great pleasure to hear from so many people who say to me, “I’ve given your book to my husband/wife/father/ mother/boyfriend/girlfriend/brother/sister as a way to explain what I feel but can’t describe.”

10. Early in Monkey Mind, you say “This is no recovery memoir, let me warn you” (p. 14), and yet, by the end of the book, you’ve managed to find a strategy to help you keep your anxiety in check. Do you consider yourself to be in recovery? What advice would you give readers who are struggling with anxiety?

I don’t consider myself to be in recovery because I don’t think anxiety is something a person can—or should—“recover” from. Anxiety isn’t just a problem; it’s an emotion, and a universal and adaptive one at that. We need anxiety in order to survive, both as individuals and as a species. That said, I am far less overwhelmed by anxiety than I once was and far more capable of keeping my anxiety in check. My experience tells me that this is because I came to think of anxiety as something very like a habit: a way of thinking and feeling that I could, with effort and dedication, learn to change.

11. What’s next for you as a writer? Since your memoir was so well received, are you considering writing more?

I’m working on a number of different projects, including some fiction and some criticism. And, to my surprise, I might not be totally done with anxiety. I find myself increasingly interested in the cultural aspects of the experience. What is it that makes not just a person but a culture anxious? How does anxiety spread? Why do so many people seem to suffer from anxiety at this particular point in time? I’ve been asking myself these questions and seeing where they lead me.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (June 1, 2013)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9781439177310

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“I read Monkey Mind with admiration for its bravery and clarity. Daniel Smith’s anxiety is matched by a wonderful sense of the comic, and it is this which makes Monkey Mind not only a dark, pain-filled book but a hilariously funny one, too. I broke out into explosive laughter again and again.”

– Oliver Sacks, bestselling author of The Mind’s Eye and Musicophilia

“Monkey Mind does for anxiety what William Styron’s Darkness Visible did for depression.”

– Aaron T. Beck, father of cognitive therapy

“You don't need a Jewish mother, or a profound sweating problem, to feel Daniel Smith's pain in Monkey Mind. His memoir treats what must be the essential ailment of our time—chronic anxiety—and it does so with wisdom, honesty, and the kind of belly laughs that can only come from troubles transformed.”

– Chad Harbach, author of The Art of Fielding

“Daniel Smith maps the jagged contours of anxiety with such insight, humor and compassion that the result is, oddly, calming. There are countless gems in these pages, including a fresh take on the psycho-pathology of chronic nail biting, an ill-fated ménage a trois—and the funniest perspiration scene since Albert Brooks’ sweaty performance in Broadcast News. Read this book. You have nothing to lose but your heart palpitations, and your Xanax habit.”

– Eric Weiner, author of The Geography of Bliss

“I don’t know Daniel Smith, but I do want to give him a hug. His book is so bracingly honest, so hilarious, so sharp, it’s clear there’s one thing he doesn’t have to be anxious about: Whether or not he’s a great writer.”

– A.J. Jacobs, author of Drop Dead Healthy and The Year of Living Biblically

“Daniel Smith has a written a wise, funny book, a great mix of startling memoir and fascinating medical and literary history, all of it delivered with humor and a true generosity of spirit. I only got anxious in the last part, when I worried the book would end.”

– Sam Lipsyte, author of Home Land and The Ask

“In this unforgettable, surprisingly hilarious memoir, journalist and professor Smith chronicles his head-clanging, flop-sweating battles with acute anxiety. . . . He’s clear-eyed and funny about his condition’s painful absurdities.”

– People (four stars)

“This book will change the way you think about anxiety…. Daniel Smith's writing dazzled me….. Painful experiences are described with humor, and complex ideas are made accessible…. Monkey Mind is a rare gem.”

– Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“Monkey Mind is fleet, funny, and productively exhausting.”

– Ben Greenman, The New York Times Book Review

“Superb writing [and] marvelous humor . . . If you're chronically anxious and want to better explain to a loved one what you're going through, hand them Monkey Mind.”

– Psychology Today

“You’ll laugh out loud many times during Daniel Smith’s Monkey Mind. . . . In the time-honored tradition of leavening pathos with humor, Smith has managed to create a memoir that doesn’t entirely let him off the hook for bad behavior . . . but promotes understanding of the similarly afflicted.”

– O Magazine

“The book is one man’s story, but at its core it’s about all of us.”

– Booklist

“[Smith] adroitly dissects his relentless mental and physical symptoms with intelligence and humor. . . . An intelligent, intimate and touching journey through one man’s angst-ridden life.”

– The Star Tribune (Minneapolis)

“A true treasure-trove of insight laced with humor and polished prose.”

– Kirkus Reviews (starred)

“Monkey Mind is a perfect 10…. Hilarious, well-informed and intelligent, Smith conveys the seriousness of his situation without becoming pathetic or unrelatable, and what’s more, he offers useful information for both sufferers and non-sufferers…. He gives us a reason to stay with him on every page.”

– Newsday

“Here's one less thing for Daniel Smith to worry about: He sure can write. In Monkey Mind, a memoir of his lifelong struggles with anxiety, he defangs the experience with a winning combination of humor and understanding.”

– Heller McAlpin, NPR.org

“For fellow anxiety-sufferers, it’s like finding an Anne of Green Gables–style kindred spirit.”

– New York magazine’s Vulture.com

“[Monkey Mind] will be recognized in the years to come as the preeminent first-person narrative of the anxiously lived life.”

– Psychiatric Times

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Monkey Mind Trade Paperback 9781439177310(2.1 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Daniel Smith Photograph by Tyler Maroney(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit