Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

• Long considered one of the most significant and original books to have come out of the surrealist movement

• Reveals the “marvelous” in works from William Blake, Edgar Allen Poe, William Shakespeare, Chrétien de Troyes, and Arthur Rimbaud; legends and folktales from around the world; classics from Ovid, Plato, and Apuleius; Masonic ritual texts, Mesopotamia’s Epic of Gilgamesh, the Popol-Vuh, Lewis Caroll’s Alice through the Looking Glass, Solomon’s Song of Songs, and Goethe’s Faust

First published in French as Miroir du merveilleux in 1940, Mirror of the Marvelous has long been considered one of the most significant and original books to have come out of the surrealist movement and Anaïs Nin suggested it as a source of inspiration, far ahead of its time.

Drawing on sacred and modern texts that share a quality of the marvelous, Pierre Mabille defines “the marvelous” as the point at which inner and outer realities are joined and the individual is simultaneously one with himself and with the world, thus recovering the true sense of the sacred. He shows how “the marvelous” goes beyond simply being a synonym for “the fantastic” to engage the entire emotional realm. Mabille cites a far-reaching range of texts, from the classic to the obscure, from Egyptian myth to Voodoo initiation ceremonies, from the ancient epic to the modern poem, from the creation myth to more contemporary visions of apocalypse. He includes surrealist analyses of works from William Blake, Edgar Allen Poe, William Shakespeare, Chrétien de Troyes, and Arthur Rimbaud; legends and folktales from Egypt, Iceland, Mexico, Africa, India, and other cultures; classics from Ovid, Plato, and Apuleius; Masonic ritual texts, Mesopotamia’s Epic of Gilgamesh, the Popol-Vuh, Lewis Caroll’s Alice through the Looking Glass, Solomon’s Song of Songs, and selections from Goethe’s Faust.

Mirror of the Marvelous actively defines the flame of the marvelous by showing its presence in those works where it burns the brightest.

Excerpt

The reflecting surface of calm water, the first natural mirror, divides the universe. On the one side, where our voluntary actions take place, are all tangible objects together; on the other, the images, the reversed, fugitive world that a breath of wind or a falling leaf distorts and obliterates. The mirror engenders our first metaphysical questions. It makes us doubt our senses. It poses the problem of illusions.

By their very nature, reflections resemble the images from which thought is constructed. They share the elusive fragility of mental representations, vanishing as quickly as they appear.

As soon as we approach the polished surface, we see ourselves. Up until that moment, we felt as if we lived enclosed in the deep warmth of our flesh, the world we knew as the obstacle limiting our movements. Now we see ourselves as if we were looking at strangers. We must learn to recognize ourselves as people like others and yet different from them in a thousand small ways that we gradually discover in our appearances. An effort of judgment and long habit are needed to link this confused mass of internal sensations with that objective representation of being, to join the I with the self.

Confronting the experience of the mirror, thought enters into an endless series of unsettling questions. Between objects and their reflections, the play of dialectical interchange never stops. One supposes, one hopes, one infers. Between the material and the immaterial, innumerable scholastic arguments are assembled. Logic, that obliging servant, proposes false certainties and false solutions. Since the images are reversed, the mind deduces that they must possess qualities and attributes opposite to those of the tangible universe.

Thanks to the mirror, we have been able to escape the confines enclosing us. We have been able to transform our feelings of existence into a representation--we have discovered ourselves. The hope is that the reverse phenomenon will occur with regard to objects. Normally perceived as the shapes their exterior surfaces take, couldn’t they, through the play of reflection, let us penetrate the mystery of their contents to arrive at their essence?

The domain of images where our immediate actions have no impact, in which our beings become objects, seems outside of the real world to us, superimposed upon it, subject to other laws. But, at the same time, the analogy between reflections and the tools of our mental life allows us to assimilate this abstract domain at the very depths of our being. Reflections and echoes lead to the center of the unconscious, to the origins of dream, to the place where desire manages to express itself in some confused way.

Thus, in front of the mirror, we are led to ask ourselves about the exact nature of reality, about the links connecting mental representations with the objects prompting them. The problem arises of reconciling human necessity, which stems from our desires, with a natural necessity that obeys implacable laws. These are the questions that allow us to reach an exact definition of the marvelous. Apart from all its charm and curiosity, all the feelings that stories, tales, and legends hold for us, outside of the need for distraction and forgetting, for pleasant or terrifying sensations, the real purpose of the marvelous voyage, as we may already understand, is to explore universal reality more thoroughly.

Lewis Carroll is one of those authors who best understands this mechanism of the imagination. He transmits it directly, without recourse to dry philosophical language. He was qualified for this task, combining a mathematician’s lucid precision with the greatest poetic sensibility. The titles of his works Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass illustrate this best. Through the play of suppositions and by a maneuver that deconstructs logic, Alice manages to break down the limits of common sense and build herself a marvelous world.

Through the Looking Glass

Lewis Carroll

In another moment Alice was through the glass, and had jumped lightly down into the Looking-glass room. The very first thing she did was to look whether there was a fire in the fireplace, and she was quite pleased to find that there was a real one, blazing away as brightly as the one she had left behind. “So I shall be as warm here as I was in the old room,” thought Alice: “warmer, in fact, because there’ll be no one here to scold me away from the fire. Oh, what fun it’ll be, when they see me through the glass in here, and can’t get at me!”

Then she began looking about, and noticed that what could be seen from the old room was quite common and uninteresting, but that all the rest was as different as possible. For instance, the pictures on the wall next to the fire seemed to be all alive, and the very clock on the chimney-piece (you know you can only see the back of it in the Looking-glass) had got the face of a little old man and grinned at her.

“They don’t keep this room so tidy,” Alice thought to herself, as she noticed several of the chessmen down in the hearth among the cinders; but in another moment with a little “Oh!” of surprise, she was down on her hands and knees watching them. The chessmen were walking about, two and two!

“Here are the Red King and the Red Queen,” Alice said (in a whisper, for fear of frightening them), “and there are the White King and the White Queen sitting on the edge of the shovel--and here are the two castles walking arm in arm--I don’t think they can hear me,” she went on as she put her head closer down, “and I’m nearly sure they can’t see me. I feel somehow as if I was getting invisible--.”

Product Details

- Publisher: Inner Traditions (April 10, 2018)

- Length: 320 pages

- ISBN13: 9781620557334

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Pierre Mabille’s Mirror of the Marvelous reflects on the strangely beautiful and often terrifying domains of visionary reality as expressed in world literature. His collection of classically unusual tales and sympathetic insightful interpretations provides the reader with an oasis for the Divine Imagination. Mabille’s association with the Surrealists helped link their aesthetic with the great tradition of Western occult symbolism. I am thrilled that Inner Traditions has brought Mirror of the Marvelous to the English-speaking world at last.”

– Alex Grey, artist and author of Net of Being and Sacred Mirrors

“One of those monumental works which to leave unread would be to renounce, once and for all, any hope of comprehending the surrealist spirit.”

– André Breton, author of Manifestoes of Surrealism

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

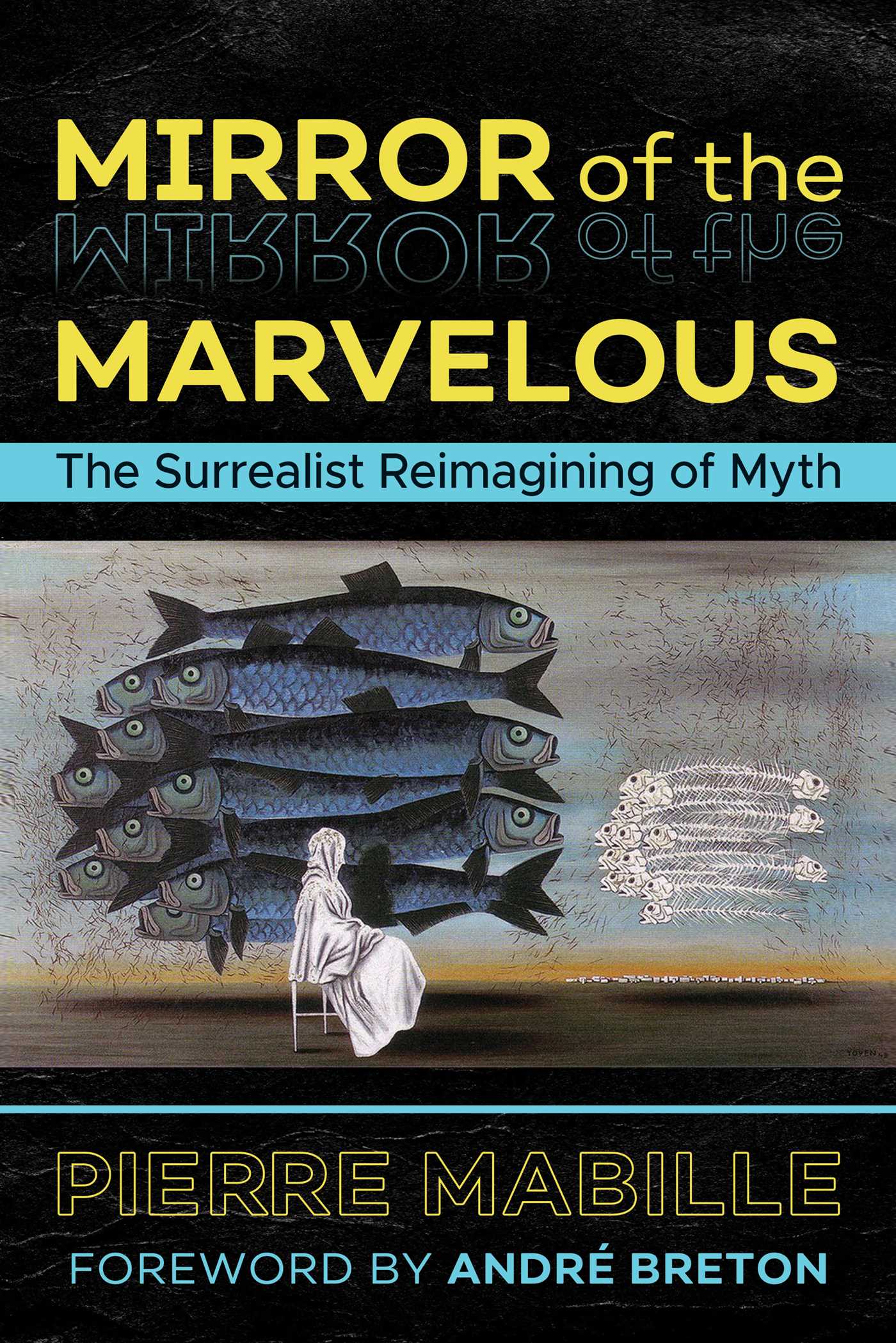

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Mirror of the Marvelous 2nd Edition, New Paperback Edition Trade Paperback 9781620557334