Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

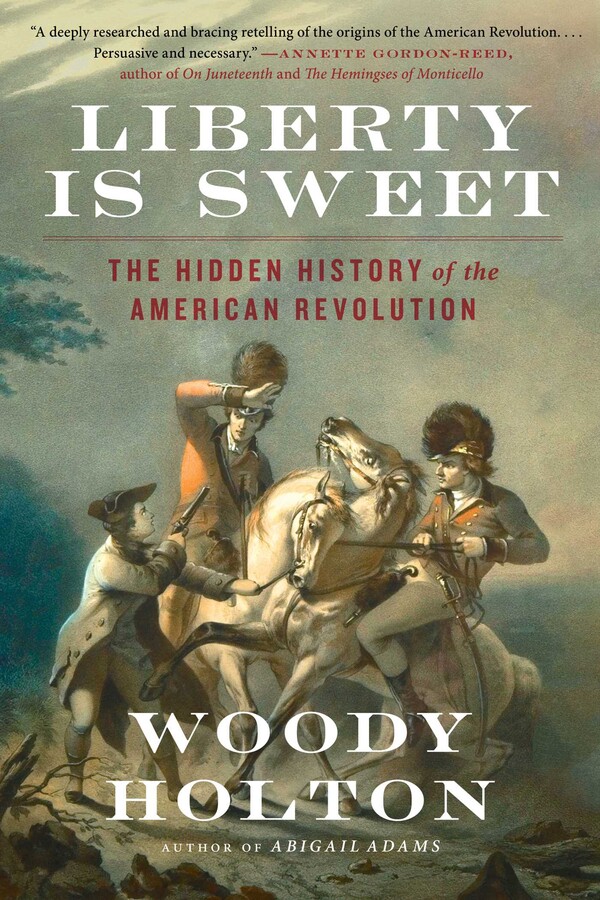

About The Book

Using more than a thousand eyewitness records, Liberty Is Sweet is a “spirited account” (Gordon S. Wood, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Radicalism of the American Revolution) that explores countless connections between the Patriots of 1776 and other Americans whose passion for freedom often brought them into conflict with the Founding Fathers. “It is all one story,” prizewinning historian Woody Holton writes.

Holton describes the origins and crucial battles of the Revolution from Lexington and Concord to the British surrender at Yorktown, always focusing on marginalized Americans—enslaved Africans and African Americans, Native Americans, women, and dissenters—and on overlooked factors such as weather, North America’s unique geography, chance, misperception, attempts to manipulate public opinion, and (most of all) disease. Thousands of enslaved Americans exploited the chaos of war to obtain their own freedom, while others were given away as enlistment bounties to whites. Women provided material support for the troops, sewing clothes for soldiers and in some cases taking part in the fighting. Both sides courted native people and mimicked their tactics.

Liberty Is Sweet is a “must-read book for understanding the founding of our nation” (Walter Isaacson, author of Benjamin Franklin), from its origins on the frontiers and in the Atlantic ports to the creation of the Constitution. Offering surprises at every turn—for example, Holton makes a convincing case that Britain never had a chance of winning the war—this majestic history revivifies a story we thought we already knew.

Excerpt

ON JULY 2, 1775, WHEN GEORGE Washington rode into Cambridge, Massachusetts, to take command of the Continental Army, he expected to be attacked at any moment by the British soldiers camped across the Charles River in Boston and commanded by Gen. Thomas Gage.1 Washington knew Gage. They had also fought twenty years earlier and five hundred miles to the southwest, near modern-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, only that time on the same side.

In the Battle of the Monongahela, on July 9, 1755, the twenty-three-year-old Washington had served as an aide to the commander-in-chief of British forces in North America, Edward Braddock. Six other future Continental Army generals also served under Braddock, as did at least one colonist who would battle the redcoats at Lexington and Concord.2 Gage led the advance troops. Daniel Boone drove a wagon and managed its woeful team. Benjamin Franklin did not accompany the army out to the Monongahela River but did more than anyone to get it there.

As the redcoats waded north across the river, fewer than three hundred French marines and provincials, accompanied by more than six hundred Native American warriors, marched down a hill toward them. Like their British counterparts, many of the French and native survivors of this battle would fight again in the American War of Independence.3

The Battle of the Monongahela was the first major engagement of the world’s first global war. Today most Americans call it the French and Indian War, though in truth it drew in numerous additional belligerents as far away as India. In most of Europe, it is known as the Seven Years’ War, though it actually dragged on for more than a decade. Canadians derive their term for it, the War of the Conquest, from one of its most dramatic outcomes: France ceded Québec and the eastern half of the vast Mississippi Valley to Britain. Actually, though, Native Americans retained control over most of that region for the rest of the century.

Exultant as they were at the outcome of the war, the British believed it had exposed fatal flaws in their relationship with their own North American colonists, and Parliament soon rolled out a package of imperial reforms. These British initiatives seemed tyrannical to the provincials, who contested every one of them. In a sense, the American Revolution, like the Seven Years’ War, began on the banks of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755. So we would do well to start there, too.

It was fitting that Braddock fought the French and their Algonquian allies in Indian country. In July 1755—as in July 1776, when thirteen British colonies seceded from Britain, and in July 1861, when eleven rebel states defeated the rest in their first major encounter—the key to the controversy was Native American land. Today West Virginia is known as the Mountain State, and western Pennsylvania is just as hilly, but over the millennia, many of the region’s streams, including the Ohio, carved out exceptionally fertile floodplains.4 In the Seven Years’ War, as the empires of France and Great Britain fought in and over the Upper Ohio Valley, they also had to contend with much older claimants: the Shawnees, Delawares, and Six Nations of the Iroquois (Senecas, Cayugas, Onondagas, Oneidas, Mohawks, and Tuscaroras).

In 1753, France had attempted to strengthen its grip on the region by constructing a fort where the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers converge to become the Ohio: modern-day Pittsburgh. The French post was known as Fort Duquesne, and Braddock’s task was to destroy it and scatter, capture, or kill its garrison.

Having served in the army for forty-five of his sixty years—somehow without ever seeing combat—Braddock had acquired a reputation as a crack administrator. In March 1755, he landed his troops at Alexandria, Virginia (just across and down the Potomac River from modern-day Washington, D.C.), where he was greeted by many of the colonists who would accompany him on his westward trek. One was an unabashed anglophile named George Washington. He had been to the forks of the Ohio before.5

Two years earlier, Washington had inveigled from Virginia lieutenant governor Robert Dinwiddie the hapless task of informing Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, the commander of French forces in the trans-Appalachian region, that he and his soldiers were squatting on Virginia property and would have to leave. During the latter stage of his journey Washington was accompanied by several Haudenosaunee (Iroquois). In a message to one of them, the Half King (viceroy) Tanaghrisson, he laid claim to the name the Iroquois had bestowed upon his great-grandfather, John Washington: Connotaucarious—“devourer of villages.”6 In his journal of the expedition, Washington referred to another of his Iroquois escorts, a young Seneca, as simply “the Hunter.” His real name was Guyasuta (often spelled Kiasutha or Kiashuta), and his and Washington’s paths would cross again.7

Washington’s party reached Fort Le Boeuf, the French headquarters on the Buffalo River in what is now northwestern Pennsylvania, on December 11, 1753. Legardeur and his officers balanced their contempt for Governor Dinwiddie’s outrageous demand with amused goodwill toward his earnest messenger. They loaded Washington down with ample food and drink for the trip home. The following year, the Virginian returned to the region, heading a party of provincial soldiers and Iroquois warriors and hoping to beat a French force to the forks of the Ohio. The French won the race, built Fort Duquesne, and sent a party to gather intelligence on Lt. Col. Washington. On May 28, 1754, he and forty Virginia provincials, goaded on by the anti-French Iroquois leader Tanaghrisson, surprised and easily defeated the reconnoiterers, who were not expecting a war. But five weeks later, on July 4, Washington and his troops had to surrender their outpost, Fort Necessity, to the French and their native allies, exchanging an abject confession of culpability for the privilege of going home.8

The following year, the news that Braddock was planning to attack Fort Duquesne by way of Virginia placed Washington in a quandary. He had long desired a commission in the British army, and serving in the expedition would gain him valuable experience, contacts, and possibly renown. But an army regulation required provincial officers to take orders from regular officers of like rank, a humiliation he could not abide. When Braddock learned of Washington’s dilemma—and that the young Virginian knew the Upper Ohio Valley as well as any white man living—he offered him an unpaid place in his official “Family” (personal staff), and Washington eagerly accepted.9

On April 12, 1755, the first of Braddock’s soldiers set out from Alexandria on their westward journey through backcountry Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. The commander-in-chief expected to find two hundred carts and 2,500 horses waiting for him in Frederick, Maryland, fifty miles to the northeast. Only one-tenth that number appeared, and one colonist reported that Braddock in his fury seemed “more intent on an Expedition against us than against the French.” Pennsylvania’s effort to supply the general had fallen victim to its internal divisions: the assembly would levy the necessary taxes only if the colony’s largest landholders, the proprietary Penn family, would pay their share. But the Penns’ handpicked governor vowed to veto any tax on their land. Nonetheless determined to combat the general’s “violent Prejudices” against Pennsylvania, and also to assist a second British army advancing up the Mohawk River, legislative leaders printed up £15,000 worth of paper currency to supply the troops.10

Meanwhile Braddock commissioned Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia to find him 150 wagons. In an advertisement that appeared in German as well as English, Franklin offered farmers silver and gold coin for the use of their wagons and teams. Describing Braddock’s deputy quartermaster general, John St. Clair, as a “Hussar”—one of the brutal light horsemen many Pennsylvanians thought they had left behind in the German states—Franklin assured them that whatever he was unable to buy, St. Clair would seize.11 Franklin did not appeal to his fellow colonists’ British patriotism, an omission that was all the more surprising in light of the deep affection for the mother country that he shared with George Washington. Indeed, while Franklin loved his adoptive hometown of Philadelphia, it would take a sudden and last-minute “Americanization” to land him on the colonial side of the imperial divide just in time to help write the Declaration of Independence.12

Franklin had the farmers bring their wagons and horses to the junction of Wills Creek and the Upper Potomac River, the staging area for Braddock’s ascent of the Allegheny Mountains. Years earlier, a group of wealthy Virginians and Marylanders calling themselves the Ohio Company had received a preliminary grant of up to 500,000 acres at the forks of the Ohio. The company also purchased animal pelts from Native American trappers and stored them at Wills Creek. Recently fortified, the Ohio Company’s storehouse was being called Fort Cumberland—modern-day Cumberland, Maryland. On May 10, when the general arrived, 150 wagons were waiting for him.13

At Fort Cumberland, Braddock welcomed a delegation representing the three nations that lived and hunted in the Upper Ohio Valley—the Shawnees, the Delawares, and a southern offshoot of the Iroquois called the Mingos. The Upper Ohio nations were inclined to help him, since they were worried about the growing French presence on their land. And their aid might prove decisive: between them, the Shawnees and Delawares boasted more than one thousand warriors. Moreover, their presence in Braddock’s army would discourage their many allies in the region from contesting its passage. But first the Delaware sachem Shingas sat down with the British commander to ascertain “what he intended to do with the Land if he Coud drive the French and their Indians away.”14

How you think Braddock replied to that question depends on which witnesses you believe. Shingas later shared his version with Charles Stuart, a white man his nation had captured and adopted. In his memoirs, Stuart claimed that Braddock announced “that the English Shoud Inhabit & Inherit the Land.” When Shingas “askd Genl Braddock whether the Indians that were Freinds to the English might not be Permitted to Live and Trade Among the English and have Hunting Ground sufficient To Support themselves and Familys,” Braddock’s reply was categorical: “No Savage Shoud Inherit the Land.”15

Stuart noted that in keeping with native diplomatic protocol, Braddock’s visitors made no reply until the following day, when “Shingas and the other Chiefs answered That if they might not have Liberty To Live on the Land they woud not Fight for it,” whereupon all of the Delawares and Shawnees and most of the Mingos left Fort Cumberland.16

Shingas’s version of his conversation with Braddock was contradicted by several British and colonial witnesses, who claimed that the general had treated him courteously. Indeed it would have been unwise and out of character for Braddock to deliberately alienate the very warriors he was trying to enlist. Perhaps the best explanation for the contradiction between the native and white accounts is that Shingas gleaned the general’s real intentions from his own long history with British colonists and from the two thousand soldiers milling about Fort Cumberland.17

One thing is certain: Braddock enlisted a grand total of eight Native Americans—all members of the roughly six-thousand-person Iroquois confederacy. Led by Scarouady, the Iroquois Half King in the Ohio Valley, they would serve as guides. Scarouady helped Braddock in order to maintain Iroquois sovereignty over the Upper Ohio in the face of Shawnee, Delaware, and French counterclaims.18

Even without many actual natives in his camp, Braddock still had the option of preparing his redcoats to fight Indian-style, as recommended by many of his American officers. That would not be necessary, he said. “These Savages may indeed be a formidable Enemy to your raw American Militia,” he reportedly told Benjamin Franklin, “but upon the King’s regular and disciplin’d Troops, Sir, it is impossible they should make any Impression.”19

By June 10, when Braddock set out from Fort Cumberland, he knew that French authorities in Québec had sent Fort Duquesne’s three-hundred-man garrison massive reinforcements: about nine hundred French and First Nations fighters. However, a report apparently originating from Native Americans living or traveling on the Buffalo River (a branch of the Allegheny known today as French Creek) indicated that a drought had left that stream too little water to float the craft transporting the French troops’ food and other supplies. That raised the possibility that Braddock could beat the enemy reinforcements to Fort Duquesne, capture it, and claim the tremendous advantage of fighting from behind its walls. With that prospect in mind, Washington, who had navigated the Buffalo two winters earlier, urged Braddock to hasten ahead with a “small but chosn Band.”20

Braddock had worn the uniform for twice as long as Washington had lived, but he respected the young American’s forest lore and heeded his advice. Neither man knew they had already lost the race: by June 18, when Braddock divided his army, the French soldiers had made it down the Buffalo River to the Allegheny. Indeed, such was the greater efficiency of water travel in this motorless age that despite the drought, the enemy reinforcements covered the six hundred miles from Montréal to Fort Duquesne three and a half weeks faster than the British could complete their 250-mile march from Alexandria.21

As the 1,300 men in Braddock’s flying column approached Fort Duquesne along an Indian path, native war parties began picking off stragglers, and anxiety spread through the ranks.22 Yet as the men gazed into their nightly campfires, some were already thinking about the years ahead. One of Franklin’s Pennsylvania teamsters, John Findley, held forth on the amazing fertility of “Kanta-ke,” three hundred miles down the Ohio River. Once the French were gone, he said, men with the gumption to settle there could make “a great speck”—enormous profits as land speculators. The idea captivated at least one of Findley’s fellow teamsters, the twenty-one-year-old Daniel Boone.23

NOT ALL OF THOSE who marched with Braddock were men. In a letter to his brother Jack, Washington said “most of the Women” traveling with the army stayed back with the baggage and Col. Thomas Dunbar’s 48th Regiment—but that fifty others were adjudged valuable enough to march ahead with the flying column. Washington had to hang back with severe dysentery, but he improved enough to join the advance troops on the evening of July 8, as they made camp about a mile east of the Monongahela River and only twelve miles from Fort Duquesne.24

In its lower reaches, the Monongahela flows mostly northwestward. The redcoats were on the right bank, as was Fort Duquesne. But to avoid a defile—a narrow path between the river and the base of a cliff, a virtual tunnel that practically invited ambush—they would have to wade the Monongahela, march two miles downriver, and then, eight miles from the fort, recross to the twelve-foot-high north bank. Surely if the French meant to attack, it would be during the recrossing. Before the men ventured back out into the river, Braddock moved them from column formation into a line of battle. As they clambered safely up the north bank, they “hugg’d themselves with joy,” convinced that there would be no ambush that day. Braddock ordered his soldiers back into their columns and moved them out under an “excessive hot sun.”25

Braddock’s conviction that the Monongahela River crossing was the best place for the French to ambush him was shared by the commander of Fort Duquesne. The previous day, Capt. Claude-Pierre Pécaudy, sieur de Contrecoeur, had ordered up an attack by a force of Canadian militiamen, French infantry, and native warriors: mostly Ottawas, Ojibwas, Mississaugas, and other Great Lakes nations but also a handful of Ohio Valley warriors, including Guyasuta, the Mingo who had hunted game for Washington less than two years earlier. Contrecoeur’s decision to deploy his First Nations allies at the river’s edge rather than in the final defense of Fort Duquesne reflected his realization that Eastern Woodlands Indians almost never contested the possession of forts, as either attackers or defenders.26 As it was, some of the natives in his 1,600-man force hesitated to strike Braddock’s army, which numbered nearly 1,400, and their objections delayed the sortie’s departure nearly two hours, preventing it from reaching the Monongahela until after Braddock’s troops had recrossed it.27

When the two armies collided just north of the river, both were surprised. Both opened fire, and the third British volley killed Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu, the French commander. Unfazed, his native allies spread out in a horseshoe pattern, occupying a hill on the British right. In short order, fifteen of the eighteen officers in the British vanguard became casualties, and the survivors fell back. Meanwhile Braddock rushed the main body forward, and the two British units became entangled. In the chaos, the few remaining officers lost contact with their men.28

The area where the British and French met was less forested than the rough country through which Braddock and his men had just marched—and probably not by accident, for Native Americans periodically burned forests to reduce cover, attracting more deer. But the vegetation was thicker than in the European fields where the British officers had learned to fight, if they had learned at all, and they struggled to convert their columns into firing lines.29 When a few men—rarely more than a platoon—managed to line up, their training did them a disservice. They had been drilled and drilled in platoon firing: the moment one man pulls his trigger, the rest must follow. But with the enemy dispersed among the trees, the first man to shoot tended to be the only one who had actually spotted a target. Many British survivors of the battle reported that “they did not see One of the Enemy the whole day,” and one attributed the growing panic to “the Novelty of an invisible enemy.”30

As native warriors scalped wounded captives, assailants’ screams mingled with those of their victims, terrifying the remaining redcoats. George Washington, who had experience in forest warfare, would later voice contempt for the redcoats, who, as he put it, “broke, and run as Sheep pursued by dogs.” Frightened sheep do not always take flight. Sometimes they bunch up, and just so with the British, one officer reporting that “the men were sometimes 20 or 30 deep, and he thought himself securest, who was in the Center.”31

All the while, Braddock rode furiously among them, constantly exposing himself to enemy fire as he tried to gather platoons into companies. Four or five horses were successively shot from under him. His secretary and two of his aides-de-camp were wounded, leaving him only Washington, still miserable from lingering dysentery and so beset with hemorrhoids that he had had to tie cushions over his saddle. When he was not carrying the general’s messages, Washington remained at his side. Lead balls pierced his jacket and hat, but he somehow escaped injury.

Washington and several of Braddock’s American officers repeated their earlier suggestion about fighting the Indians in their own way. The rear guard, apparently acting on the orders of Capt. Adam Stephen, who had been with Washington at Fort Necessity, adopted this tactic and fared better than the rest. But Braddock refused, and when he found men taking cover behind trees, he used threats and the flat edge of his sword to force them back into line.32

Braddock was probably wise not to change tactics under fire, for numerous men sent into the forest would surely have run away. When scores of soldiers took to the woods in defiance of Braddock’s orders, many were mistaken for enemies. “The greatest part of the men who were behind trees, were either kill’d or wounded by our own People,” wrote one survivor. As many as two-thirds of the redcoats who fell that day were victims of friendly fire.33

Surprisingly, the natives also had a technological advantage over the redcoats. Most of their firelocks were rifles, not muskets, as indicated by the sound they made when fired—“Pop[p]ing shots, with little explosion, only a kind of Whiszing noise”—and by the smaller-than-normal lead balls that surgeons later extracted from the few wounded who made it off the battlefield; rifles fired smaller rounds. Rifles were seldom used on traditional European battlefields, since they did not carry bayonets and took three times longer to load. But in the forest, where trees and underbrush prevented bayonet charges, where the fighter could take cover while reloading, and where the target was not a platoon but one individual at a time, the advantage passed to the rifled barrel, which sent the ball spinning toward its target, greatly improving accuracy, range, and stopping power.34

Many of Franklin’s teamsters cut horses from their traces and rode off, but most of the troops and some of the teamsters (including Daniel Boone, per his own later claim) held firm for three hours, until they ran out of ammunition and a musket ball threw Braddock himself from his horse. Then the men began to break and run. One wounded officer begged the soldiers racing past to stop and help him, but none would. Finally, he reported, “an American Virginian” came along and said, “Yes, Countryman… I will put you out of your Misery, these Dogs shall not burn you.” The man “levelled his Piece at my Head, I cried out and dodged him behind the Tree, the Piece went off and missed me.”35 The Virginian ran on, and the wounded officer got help from someone else.

The soldiers scrambled down the steep northern bank of the Monongahela and waded out into the stream. The Indians “shot many in the Water,” but pursued the rest no farther, preferring to harvest scalps, plunder, and captives back at the battlefield. An officer described the road to Dunbar’s camp as “full of Dead and people dieing who with fatigue or Wounds Could move on no further; but lay down to die.” The first survivor straggled in at 5 a.m. on July 10. About one-third of Braddock’s officers were dead, with another third wounded. Enlisted men suffered in the same proportion. Altogether, of a force of fewer than 1,500, approximately 450 were killed and roughly the same number were wounded. At least 70 of the injured men eventually died, pushing the fatalities over 500. On the other side, only about 28 French infantrymen and 11 natives were killed.36

Among the British casualties were the majority of the fifty or so women who had marched with the flying column. Many died on the battlefield, a few escaped, and others were taken captive, along with some of the men. Bringing home captives was a principal goal of native warfare and won a warrior greater renown and more spiritual power than bringing in a scalp, owing to the greater danger and difficulty. Many male captives would be ritually tortured to death, but some of the men and most of the women would be adopted as replacements for deceased kin.37

Braddock lingered for four days, finally succumbing as the retreating army camped near the ruins of Fort Necessity, where Washington had suffered his own humiliating defeat the previous year. Washington made sure the general was buried under the road so that (as one veteran put it) “all the Wagons might March Over him and the Army [as well] to hinder any Suspision of the French Indiens,” lest they “take him up and Scalp him.” At Braddock’s death, the command of the expedition fell to Col. Dunbar. Spooked by the survivors’ accounts, he opted not to renew the attack and would not even accede to local officials’ pleas that the army at least remain at Fort Cumberland in order to help protect frontier settlers. Instead he announced plans to march to Philadelphia; Washington and others scoffed at his going into “Winter Quarter’s” in August.38

During Braddock’s westward crawl across the Allegheny Mountains in June, native war parties had taken scalps and captives as far east as Fort Cumberland, but after July 9, the raids multiplied all along the frontier. Among the attackers was Shingas, the Delaware leader who had offered to fight for the British in return for quiet possession of his land.39

White colonists also faced another danger. Less than a week after Braddock’s defeat, King George County, Virginia, slaves “apear’d in a Body” at the home of Charles Carter, and Carter’s father, who commanded the county militia, sent a posse after them. Virginia governor Robert Dinwiddie recommended making “an Example of one or two” of the slaves—by which he meant trying them for their lives. A week later, Dinwiddie informed the earl of Halifax that Virginia slaves had been “very audacious on the Defeat on the Ohio”; he agonized over how many of each county’s militiamen to send against native raiders and how many to leave behind to guard the slaves. Dinwiddie reported that “These poor Creatures imagine the Fr[ench] will give them their Freedom,” and this was a real possibility. The king of Spain, who often joined his French cousins in intermittent warfare against Britain, had offered freedom to any British slave who could make it to Spanish Florida, and in 1739 this invitation had prompted a slave revolt near Charles Town (which would not be shortened to Charleston until 1783), South Carolina. It was the largest ever seen in colonial British North America. Like many white Virginians, Dinwiddie owed his fortune to slaves but also feared them. “We have too many here,” he wrote.40

Others shared the governor’s fears. In the wake of Braddock’s defeat, Samuel Davies, a Presbyterian minister in Hanover County, Virginia, warned his flock of “the danger of insurrection and massacre from some of our own gloomy domestics.”41

NO ONE COULD HAVE anticipated that one survivor of the Battle of the Monongahela, George Washington, would one day command an American army of insurrection or that his unofficial wagon master, Benjamin Franklin, would polish the rebels’ declaration of independence before sailing off to seek a French alliance. After all, both men had helped Braddock in hopes of deepening their connections to the mother country, and after the general’s death and defeat, both redoubled these efforts. Franklin joined the campaign to take Pennsylvania away from the Penn family and turn it into a royal colony.42 Washington, who had enlisted with Braddock partly in hopes of procuring an army commission, continued that pursuit after 1755. Had he been commissioned, he might still have fought in the American War of Independence, just on the other side. Although Washington’s hopes for immediate professional preferment died with Braddock, he had made valuable contacts, especially with Thomas Gage.

Why did Americans like Washington and Franklin later turn against their beloved British empire? The roots of the American Revolution ran even farther back than the Seven Years’ War. At the conclusion of their previous clash with France and Spain (the War of Jenkins’ Ear, 1739–1748), the British resolved to exert greater control over their North American possessions. In 1751, Parliament prohibited New England from printing paper money that was legal tender, meaning that creditors were required to accept it. (Even today, American currency is “legal tender for all debts.”) Royal officials hoped to extend the currency ban to the provinces south of New England—and also crack down on colonial smuggling and rein in the real estate speculators who engrossed vast quantities of native land. But then the disaster on the Monongahela brought British politicians heart and soul into the crusade against the French and Indians.43 Victory would depend, above all, on whether the colonists also fully committed, so while the war raged on, Britain had to wink at their transgressions.

Viewed from London, though, the North Americans’ actions during the Seven Years’ War only strengthened the case for root-and-branch reform. Textbooks err in stating that the reason Parliament tried to tax the colonists in the 1760s was to reduce the debt it had incurred fighting the French. But the war did pave the way for the Revolution in another way: by teaching British officials that they needed to overhaul the empire.

Many of the lessons Britain thought it learned during the Seven Years’ War had to do with groups that Braddock had not noticed until too late and that even today remain invisible in most accounts of the origins of American Revolution. For example, in the wake of the disaster on the Monongahela, Britain came to believe that it could never defeat France and Spain in North America without Native American allies. To win the natives over, imperial officials promised to keep their colonists off their land.44

Britain somewhat succeeded at placating the Native Americans—but at the same time infuriated a significant portion of its own colonists: those who had hoped to make or improve their fortunes selling Native American land. Many of these men had fought at the Monongahela and learned their own lessons there: not that the First Nations had to be appeased but that their land possessed immense potential value—all the more so now that army engineers had built a road to it. Here was the most important way in which the Battle of the Monongahela set the stage for the American Revolution: British officials and American colonists came out of it with conflicting ideas about Indians.

Later events of the Seven Years’ War taught British officials additional lessons that colonists wished they had not learned. In 1760, when black Jamaicans carried out Britain’s largest slave revolt yet—suppressed only at great cost to the British army and navy—they gave London still another reason to shorten the American colonists’ leash. Near the close of the interimperial struggle, France deeded Louisiana, which included New Orleans and all of the land along rivers flowing into the Mississippi from the west, to Spain. The combined Spanish and Native American threats contributed to the British cabinet’s fateful December 1762 decision to leave twenty battalions—ten thousand troops—in America after the peace treaty. British taxpayers were already straining to pay the interest on the British government’s debt, which had nearly doubled during the war, so imperial officials decided to push the cost of the peacekeeping troops onto the Americans they protected. That meant taxing them.45

Like the British government, many of the mother country’s most powerful interest groups learned important lessons from the Seven Years’ War. The paper money that the Pennsylvania legislature spent provisioning Braddock’s soldiers held its value, but much of the colonial currency issued later in the prolonged conflict depreciated, often dramatically. In equal measure, hyperinflation benefited debtors but cheated creditors, including British merchants, who went to war against the colonists’ paper money.46

The Seven Years’ War also awakened other interest groups. Even as British and French soldiers shot and stabbed each other, merchants based in Philadelphia, Newport, Boston, and other colonial ports illegally traded with the French sugar islands in the Caribbean. The most vocal opposition to this smuggling came from the British Caribbean slaveholders who competed with the French (and the Spanish and Dutch) for the privilege of supplying North America with sugarcane, especially in the form of molasses, the principal ingredient in rum.47

In the four arenas of taxes, territory, treasury notes (paper money), and trade—conveniently summarized as the four Ts—the colonists had long violated official British policy. Then the Seven Years’ War freed them to stray even further from imperial orthodoxy. If Britain came down too hard on the colonists’ smuggling, tried to tax them, or burned the crude cabins they built beyond the Anglo-Indian boundary, it would jeopardize their support for the war. Thomas Hutchinson, who was both lieutenant governor of Massachusetts and chief justice of the colony’s superior court, became so unpopular, especially for his aggressive pursuit of smugglers, that the legislature voted to cut his salary. But there was nothing he could do—at least not yet. “We wish for a good peace with foreign enemies,” Hutchinson wrote a friend in 1762. “It would enable us to make a better defence against our domestick foes.”48

Hutchinson was not alone. British politicians as well as hapless colonial officials spent the final years of the Seven Years’ War drawing up plans, pigeonholing them, and anxiously awaiting the end of the war.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (January 4, 2023)

- Length: 800 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476750385

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"With Liberty Is Sweet, Woody Holton once again troubles the mythical narratives of our founding and the hagiography of our 'founders' to reveal the dynamic, complicated and multiracial pressures that led to the creation of the United States. This book rightly decenters the almost exclusively white revolutionary narratives that we've all been taught and instead makes visible the influence and agency of Black and Indigenous people as well as white women, who together played such a critical, if erased, role in creating this multiracial nation. This book unsettles the reader in the best possible way, and shows once again how the simplistic histories of our founding fail to explain the divided country in which we all live."

– Nikole Hannah-Jones, staff writer for The New York Times Magazine and creator of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “1619 Project”

“Liberty is Sweet is a deeply researched and bracing retelling of the origins of the American Revolution. Holton details the central role that European hunger for Indian land— and the differing views on Indian policy between British officials and Anglo-American colonists——played in the crises that led to revolution. This persuasive and necessary account will challenge all who think they know exactly why the 13 colonies opted to leave Great Britain.”

– Pulitzer Prize-winning author Annette Gordon-Reed, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor at Harvard University, author of On Juneteenth

"Even readers who think they know all about the Revolution will find here a much broader, provocative narrative and new perspectives."

– Booklist (starred review)

"In his meticulously researched, beautifully calibrated Liberty Is Sweet, historian Woody Holton adds necessary nuance, building on . . . stories previously marginalized (or invisible) in our narrative of the nation's birth while illuminating a collective yearning to form a more perfect union. . . . Holton's painstaking yet vivid military coverage is one of the book's crowning achievements."

– Hamilton Cain, Minneapolis Star-Tribune

"[Holton] has a gift for pacing and narrative detail . . . . One of [his] aims is not simply to offer an 'inclusive' history—one where ordinary people are just added to a familiar frame—but to show us how including a wider swath of society can help us rethink the picture itself."

– Eric Herschthal, The New Republic

"A spirited account of the Revolution that brings everybody and everything into the story."

– Gordon S. Wood, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for The Radicalism of the American Revolution

"A thoroughgoing work of scholarship that debunks many myths about the American Revolution by incorporating the full story involving Native Americans, African Americans, and women as participants. . . . Immensely readable. . . . A rich, multifaceted work showing how the U.S. has always been a multiracial nation."

– Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

"In this provocative and wide-ranging book, Woody Holton astutely probes the causes, course, and consequences of our complex revolution. While carefully covering the usual leaders of the new nation, Liberty is Sweet also deftly explores the lives of common men and women, of diverse races, who displayed uncommon courage in pursuing their clashing visions of equality and freedom."

– Pulitzer Prize-winner Alan Taylor, author of American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804

"Holton’s exhaustive, masterfully written chronicle demonstrates that the Revolution was much more than a movement instigated by the political ideologies of a handful of elite, revered (although flawed) Founding Fathers against the British parliament and king. This book will be pivotal for scholars and requested by American history enthusiasts."

– Library Journal (starred review)

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Liberty Is Sweet Trade Paperback 9781476750385

- Author Photo (jpg): Woody Holton Photograph by Tony MacLawhorn(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit