Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

A guide to successful community moderation exploring everything from the trenches of Reddit to your neighborhood Facebook page.

Don’t read the comments. Old advice, yet more relevant than ever. The tools we once hailed for their power to connect people and spark creativity can also be hotbeds of hate, harassment, and political division. Platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter are under fire for either too much or too little moderation. Creating and maintaining healthy online communities isn’t easy.

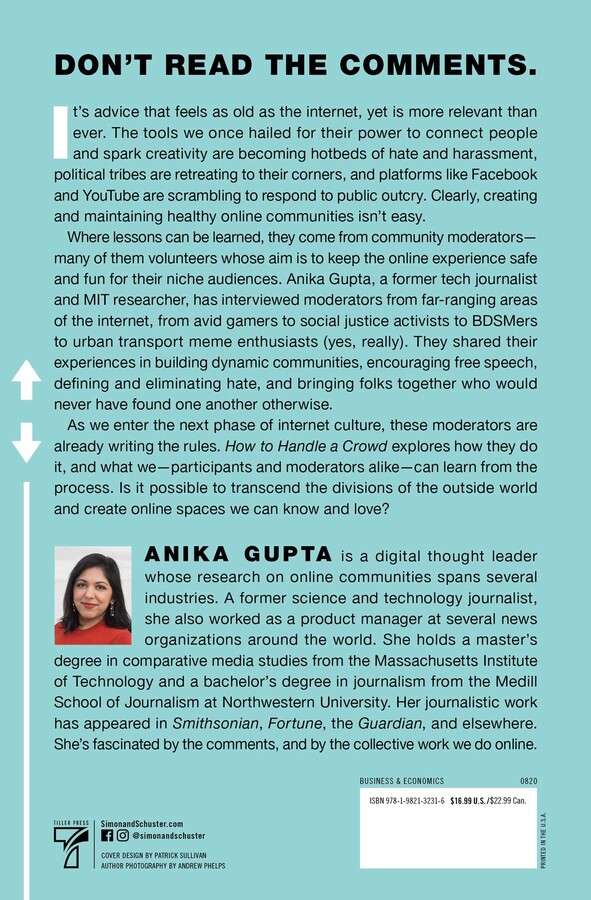

Over the course of two years of graduate research at MIT, former tech journalist and current product manager Anika Gupta interviewed moderators who’d worked on the sidelines of gamer forums and in the quagmires of online news comments sections. She’s spoken with professional and volunteer moderators for communities like Pantsuit Nation, Nextdoor, World of Warcraft guilds, Reddit, and FetLife.

In How to Handle a Crowd, she shares what makes successful communities tick – and what you can learn from them about the delicate balance of community moderation. Topics include:

-Building creative communities in online spaces

-Bridging political division—and creating new alliances

-Encouraging freedom of speech

-Defining and eliminating hate and trolling

-Ensuring safety for all participants-

-Motivating community members to action

How to Handle a Crowd is the perfect book for anyone looking to take their small community group to the next level, start a career in online moderation, or tackle their own business’s comments section.

Don’t read the comments. Old advice, yet more relevant than ever. The tools we once hailed for their power to connect people and spark creativity can also be hotbeds of hate, harassment, and political division. Platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter are under fire for either too much or too little moderation. Creating and maintaining healthy online communities isn’t easy.

Over the course of two years of graduate research at MIT, former tech journalist and current product manager Anika Gupta interviewed moderators who’d worked on the sidelines of gamer forums and in the quagmires of online news comments sections. She’s spoken with professional and volunteer moderators for communities like Pantsuit Nation, Nextdoor, World of Warcraft guilds, Reddit, and FetLife.

In How to Handle a Crowd, she shares what makes successful communities tick – and what you can learn from them about the delicate balance of community moderation. Topics include:

-Building creative communities in online spaces

-Bridging political division—and creating new alliances

-Encouraging freedom of speech

-Defining and eliminating hate and trolling

-Ensuring safety for all participants-

-Motivating community members to action

How to Handle a Crowd is the perfect book for anyone looking to take their small community group to the next level, start a career in online moderation, or tackle their own business’s comments section.

Excerpt

Chapter 1. Building Bridges 1. Building Bridges

Make America Dinner Again

How I Met MADA

I met Justine Lee for the first time in New York. We’d “met” online months before, while working together on a podcast project about Asian American life. I asked her for suggestions for whom to profile in this book; she recommended herself. Over a couple of hours, Justine told me her story. Since October 2017, she and her friend Tria Chang have run a Facebook group called Make America Dinner Again (MADA). The name pokes fun at partisan rhetoric, but the group has a serious purpose: to encourage understanding and dialogue among people with differing political views. Justine and Tria started the group after the 2016 presidential election, and it now has almost seven hundred members. Those who want to join have to apply by answering a few questions on Facebook; the founders read each application thoroughly and personally. As MADA has grown, they’ve accepted new members with an eye toward political balance; Justine says the group today includes roughly equal numbers of self-identified liberals and conservatives, as well as many other perspectives. The two of them, along with nine other moderators, oversee debates about the most divisive political topics in American discourse. Recent posts include one comparing restrictions on gun ownership to restrictions on book ownership, another asking whether or not a Holocaust-denying school principal should have been fired, and a third asking how San Francisco can humanely resolve escalating rates of homelessness.

Their group is part of a growing movement, born in the run-up to and wake of the 2016 presidential election, focused on building bridges across what seems to be an ever-widening political divide. In any given week, the MADA moderators research and post articles for the wider group to discuss, contact group members one-on-one to offer advice on the tone or content of their posts, or—in Justine’s case—read through short surveys filled out by people who want to join the group. But their real work is trying to shore up common ideals in a divided world, building slim but strong bridges across the divide of partisan opinion. Justine refers to this type of work as “translating.” The group is sometimes fractious, sometimes hopeful, and often challenging. But in working there, Justine and Tria have established an interesting online home.

The Lost Art of the Dinner Party

MADA grew out of Justine and Tria’s feelings about the 2016 election. A self-described political liberal living in San Francisco, Justine says she woke up in a daze the day after Donald J. Trump was elected president. She didn’t know how to respond. She wasn’t alone: liberals across the country were torn and dismayed. In a popular blog post written right after the election, political science professor Peter Levine outlined several potential responses that the left could make. These possible responses included things like “winning the next election,” “resisting the administration,” and “reforming politics.” They also included “repairing the civic fabric” via “dialog across partisan divides.”1 This last category is the one that Justine and Tria would come to belong to.

Justine had just finished a public radio internship, which had exposed her to local politics. But she’d found politics to be “inaccessible and a little overwhelming.” Instead she enjoyed the “human stories,” in part because “I’ve always believed that there are multiple sides to a story.” That curiosity about other people, and a focus on the human face of political debates, would become the core principles of MADA.

“Dialog across partisan divides” sounds great in theory, but is difficult in practice. In a June 2016 study by the Pew Research Center, nearly half of self-identified Republicans and Democrats said they found discussing politics with someone with opposing political views to be “stressful and frustrating,” and more than half said that they left such conversations feeling like they had less in common than they originally thought.2 Maybe just as troubling, at least from a national unity perspective, was that Republicans and Democrats saw each other in a personally poor light, ascribing negative qualities like laziness or closed-mindedness to those on the other side of the political divide.3 Researchers refer to this type of partisan dislike as “affective polarization.” In a seminal 2012 paper, the researchers Shanto Iyengar, Gaurav Sood, and Yphtach Lelkes demonstrated that affective polarization in the United States had risen dramatically since 1988, as measured by things like whether or not people would be upset if their child married someone from a different political party. In another paper, published in 2019, a group of researchers suggested that affective polarization could have serious consequences: “Partisanship appears to now compromise the norms and standards we apply to our elected representatives, and even leads partisans to call into question the legitimacy of election results, both of which threaten the very foundations of representative democracy.”4

In the months before the election, Justine says she saw political conversations break down, time and again, in her own social media feeds. People often talked past each other.

“Anytime there was a news article posted on our FB feeds, we would see it in the comments. People would make a statement in response to the headline. They would come out really strong, with almost no room for dialogue.” The worst, she says, were the comment sections on news organizations like Fox News or CNN, which she says turned into a “a mass of name-calling and trolling and inflammatory language.”

Platforms like Facebook had enormous reach and scale, but neither their technology nor their business models prioritized the facilitation of wide-ranging conversations. On the contrary, algorithms that powered popular social media sites often encouraged like-minded bubbles. A popular Wall Street Journal project from the time, called Blue Feed, Red Feed, compared how liberal and conservative Facebook news feeds featured different stories, from different outlets, with different slants.5 “If you wanted to widen your perspective and see things from a broad range of backgrounds, you would have to go and like the pages yourself. Facebook’s product makes it hard to do this,” Jon Keegan, the project’s creator, told media industry site NiemanLab in May 2016.6

But there was a flip side to the name-calling: entirely homogeneous spaces where people never interacted with anyone who had opposing views.

“If it was something that was posted on our friends’ feeds… everyone was in agreement, but it almost felt narrower still,” Justine said.

She recruited her friend Tria Chang, a wedding planner who also lived in San Francisco, to host a dinner party for people with opposing political views. Their hope was that under the auspices of a shared meal, Democrats and Republicans might discover even more common ground.

Tria already had experience with unusually tense events—weddings, she says, “are more complex than people” imagine. A lot of the tension at weddings lives beneath the surface—in part because people repress the “negative but natural emotions” that they might have about, say, a friend getting married and leaving them behind, or a child embarking on a new and independent life stage. A party among people with different political views can feel the same way: barely comfortable, and then only if people skirt the issues they really care about. Justine and Tria wanted to bring these sources of tension to the surface, and in talking about them, try to make people more comfortable with hard conversations. Doing it within the safe and familiar ritual of dinnertime would, they hoped, make participants feel more secure.

“We’re sharing a meal together, there’s already this understanding that we’re all coming with good intentions,” said Justine about the choice.

The dinner party carries a lot of weight as a symbol and stand-in for social life. In the bestselling 2000 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, political scientist Robert D. Putnam traces several contributing factors in the decline of American civic engagement over the past several decades. He spends a lot of time talking about the dinner party, noting that “Americans are spending a lot less time breaking bread with friends than we did twenty or thirty years ago.”7 In the ancient world, it was a deep and unpardonable offense to break bread with someone and then betray that hospitality, either in word or deed. Texts from the Odyssey to the Bible describe the dreadful character of—and dire consequences for—ungrateful guests. The ritual of dinner runs deep in our blood, certainly deeper than partisan divides. “Food can act as a conversation starter, but also as a buffer, in some way. If there’s nothing to talk about, if it’s awkward or uncomfortable, you can talk about the food in front of you,” Justine said. She grew up cooking with her family, while Tria organized dinner parties for a living. They liked the in-person element of a dinner, characterized by long and deep discussion—the opposite of the impersonal, quick-take attack culture they saw online.

If the idea of a brief conversation with a political opponent raises most people’s hackles, a structured three-hour dinner probably sounds like torture. Justine and Tria’s initial idea attracted resistance from both conservatives and liberals, Justine says. Activist friends preferred to focus on direct action in response to the election. The two of them knew very few conservatives, so they took out Facebook ads to try to recruit some. The ads, featuring what they thought was an appealing photo and a fun message, backfired. Conservatives—the minority in deeply liberal San Francisco—feared that the dinner invitation might be a ploy to expose or humiliate them. They also had no idea who Justine and Tria were—after all, relationships are built on trust, and Justine and Tria had yet to build any among San Francisco’s conservative population.

The women soon realized that one of the first things they would have to do was “humanize” the people on the other side of the voting divide, including to themselves. After the election, Tria says she was briefly afraid to leave the house. She associated Trump with sexism and racism, and as a woman of color, she says she felt personally targeted by all the votes that had been cast for Trump. She “felt this fear brewing in me, and I know that fear can quickly turn to hate and I didn’t want to be walking around filled with hate because that would be… unhealthy for… my community.” In order to build bridges, Tria had to step away from that sense of fear, toward a sense of optimism and openness. They eventually recruited some conservative guests through their wider social network instead. They asked each potential participant to answer a few brief questions in order to get a sense of their goals and discussion style. As the day for their first dinner party neared, they began to think about how they, as the facilitators, could help their guests reach this same attitude of openness and optimism.

They also attended to logistics. Pizza felt like a familiar and neutral food choice, and they chose a restaurant in downtown San Francisco that was easily accessible via transit. On a drizzly weeknight in January, they opened the doors. When attendees made their way to the restaurant’s private room, they found special printed menus waiting for them, as well as dice and kazoos laid out on the tables.

The dice were part of an introductory game. Each side of a die corresponded to a question that attendees could ask each other. Questions included things like “Who in your life has influenced you the most?” and, appropriately for the venue, “Given the choice of anyone in the world, who would you want as a dinner guest?” The kazoos were to keep things comfortable: if guests needed a moderator to intervene in the discussion, they could toot the kazoo to get Justine or Tria’s attention.

Justine and Tria planned the evening down to the minute, even going so far as to write out instructions and dialogue for themselves in a detailed “run of show” document. The first part of the dinner, right after people arrived, was a time for “softball questions,” things like “Where are you from?” and “What made you interested in coming to dinner tonight?” Justine and Tria wrote down the following advice for themselves, the moderators:

Give each speaker our totally absorbed and undivided attention and empathy, whatever they’re saying. Some “heavy talkers” will need to be interrupted. Some more shy folks will need to be drawn out. That’s our main job, to ensure that a diverse range of speakers are heard and to perhaps offer a comment or insight here or there.

The document offers a clear perspective on both their strategy and their priorities: for example, they rank communication and listening above changing people’s minds. (In fact, the idea of changing people’s minds doesn’t appear as a goal anywhere in the document, or really, in their moderation philosophy.)

After the softball questions, the group paired off to get to know each other better. They talked about whom they’d voted for in the recent election and why. Afterward, for the final half hour of the dinner, the group came together to discuss more sensitive matters. Justine and Tria wrote down questions like:

At the end of the dinner, the moderators passed around sticky notes. People wrote down their hopes and dreams for the country. They put their sticky notes up on a wall, and found points of similarity and difference.

The group ended up discussing only three of the scripted questions. Once lubricated with drinks and food, guests found their own rhythm and the conversation never lagged. At the end, when it came time to share hopes and dreams, the group found several points of commonality, including a dislike for the way the media had covered the most recent election, and a hope for more support for the middle class under the new president.

Reducing partisan distrust is difficult because it’s hard to pinpoint what exactly causes this type of distrust, and also because political identity is complex and interacts with many other aspects of self. Nonetheless, research has suggested that focusing on similarities instead of differences—like Justine and Tria did with their Post-it Note exercise—can help.8 Both liberals and conservatives tend to overestimate the extremity of other people’s political views, even within their own party, so gatherings that bring together those with more moderate views could help counteract that bias.9

Justine and Tria went home exhausted, but also hopeful. Justine felt that the evening provided a powerful counter-response to their critics. It was “just a… gathering at the end of the day,” she acknowledged, but “it is possible.”

They didn’t plan to repeat the dinner for several months. But a journalist who attended the first dinner wrote a story that ran on National Public Radio. Production companies and journalists reached out to Justine and Tria to organize more dinners, and they got emails from interested participants and hosts all over the country. What began as a one-off dinner grew into a series, and eventually into a network, with chapters in several major cities, each chapter headed by a local organizer. But their concept remained emphatically in-person, among co-located participants, until later in 2017.

The Opposite of the Comments Section

It’s not hard to find examples of online political discussions run amok. When Lisa Conn joined Facebook as an employee in the summer of 2017, she wanted to find examples of the opposite: online political discussions that had helped people learn and find common ground. Before joining Facebook, she was a product manager at the MIT Media Lab and worked on a project that tracked how people talked about politics, elections, and policy on Twitter. Like others doing similar work around the country, she and her colleagues found that social media—in theory, a powerful tool for creating community—could also create closed networks of conversation among like-minded people. “Giving the world power to build communities doesn’t necessarily bring the world closer together,” she said. “Building communities can actually tear the world apart, by limiting people’s contact with those who have opposing views.”

It was a finding that Facebook’s leadership had begun to appreciate as well, as they tried to figure out the role that Facebook should play in society. The company had started to receive complaints that its platform and algorithms didn’t do enough to protect users’ privacy or halt the spread of misinformation. News reports had surfaced that Cambridge Analytica, an election data firm based in the UK, had accessed millions of Facebook users’ personal data without consent, and used this information to help conservative politicians get elected.10 All of these things presented serious challenges for Facebook’s platform and philosophy. In 2017, the company changed its mission statement from “Making the world more open and connected” to “Give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together,” a shift toward actively promoting cohesion.11 In a video interview with CNN Tech, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg described the company’s new mission: “Our society is still very divided, and that means that people need to work proactively to help bring people closer together.”12

Lisa, who proudly says her grandmother was a civil rights activist, wanted to know if, through active and thoughtful moderation, online spaces could be made to do the opposite of what her research team had observed at MIT. Could online discussions encourage dialogue among people with diverging views? Despite what she describes as a lack of popular trust in the Facebook brand at the time, she was “genuinely concerned about the ways in which extremism and polarization were flourishing in social media.” Her goal was to identify possible improvements to Facebook’s Groups feature, by learning from people who were bridging gaps and fighting polarization. Soon after she started at Facebook, she met Justine and Tria through a colleague.

At the time, MADA was still an in-person group. The three of them talked about whether there could be a way to extend the MADA philosophy into a Facebook group format. Justine and Tria had hesitations. After all, they’d formed MADA as a counter-response to the impersonal, attack-driven culture they saw in their own social media feeds. Many of the dinner’s focal moments involved participants looking into one another’s eyes and responding to one another in real time. These types of conversations give people plenty of chances to observe what researchers refer to as “symbolic cues”—a wink, a shrug, a sigh—that can be just as telling as their actual words.13 Justine and Tria considered the act of paying attention to others’ symbolic cues part of the “humanization” process. That level of context gets lost online, when people don’t always know each other’s real names, don’t see nonverbal cues, and can enter and leave conversations without notice.

But an online group offered benefits, too—including scale, reach, and potential longevity. Justine and Tria were already facing challenges as MADA grew. The first was geography—they didn’t have enough hosts to meet demand, especially in less densely populated areas. Second, they wanted to capture the energy and enthusiasm that participants felt after a dinner by giving them a place to keep the conversation going, but that wasn’t always an option in physical space.

They perceived other benefits, also. There are plenty of people for whom an in-person dinner is not accessible, because of temperament, ability, or other reasons, but an online group might be. Among online platforms, Facebook had enormous scale and ubiquity, as well as tools for groups that would, in theory, give moderators greater control and agency in guiding conversation. With careful, thoughtful, and diligent moderation, perhaps an online version of MADA could help keep the spirit of the project alive.

They gave the same careful treatment to their online moderation practices that they had to their offline moderation. Several weeks before launching the Facebook group, Justine, Tria, and Lisa drew up a three-column spreadsheet identifying eleven top-level MADA “goals.” These included things like “give people the agency to ask for help,” “show that people’s views are complex,” and “connect people 1:1 after the dinner.” In the next column of the spreadsheet, they listed how MADA achieved each of these goals through in-person moderation practices. For example, at an in-person dinner, participants got noisemakers—like the kazoos from the first dinner—or a set of red and green cards that they could hold up to show the moderators that they needed help or felt uncomfortable.

In the third column, the three brainstormed ways to achieve these same goals in the Facebook group. For example, they proposed “green/yellow/red emoji” and a “bell emoji” as ways participants could indicate discomfort or get moderators’ attention. To help people show a variety of views, they suggested “create a poll with multiple answers,” and to build one-to-one connections, they considered “encourage friending.”

They built the group slowly over time, trying to maintain a balance of political perspectives. Just like the in-person dinners, they asked everyone who wanted to join to answer a few initial questions. In reviewing hopeful participants’ answers, Justine often also looked at the person’s public Facebook profile to get a sense of how they expressed themselves online.

Some of these ideas worked better than others. The bell emoji, for example, never quite took off. Instead, Justine says, they noticed that other members of the group started stepping into heated discussions to remind participants of the rules. As the group expanded, Justine and Tria began to approach some of these extra-helpful members as potential moderators. This is one way to expand a moderation team—by offering additional responsibility to people who are already informally taking on work.

Mark Fosdal was one of those people. He’s in his fifties, grew up in the Midwest, and describes himself as “conservative and a Christian.” He discovered MADA while trying to enhance his social life.

“I had a lot of bad online dates where you sit there with nothing to talk about,” he said, describing himself as the type who enjoys “discussing over dinner [more] than going out to the clubs.” He found a MADA listing on Meetup and attended his first dinner in the basement of a church in Seattle. He remembers a crowd of twenty to thirty people. They started with small exercises that turned into a larger group discussion. He attended another in-person MADA dinner at a private home, a smaller event that he says was more of a “structured discussion” and “controlled environment.” At these first few dinners, he got a sense of “the different flavors” that different hosts brought to MADA, but also saw that the group was united around a “similar theme of sitting down, listening.” Drawn in by the in-depth discussions he was having, he decided to host his own dinner for ten to eleven people.

For Mark, who says he loves conversation but is also an introvert, the MADA dinners provided not just a social outlet but also an avenue for expression and community. Many of his friends didn’t share his conservative leanings. “For the past several years in the Pacific Northwest, there’s an unspoken opinion that you keep your opinions to yourself if you fall into that category.” The group gave him a chance not only to express his own views but to challenge them. He says he left his first dinner feeling “excited, not alone.”

He went to a few more in-person dinners before he found the MADA Facebook page and started contributing there. He eventually started an in-person MADA chapter in his hometown of Bellevue, Washington, and became a moderator of the online group. “I think I stood out in having a point of view and being curious at the same time,” he said. The fact that he had friends with different political views, Justine says, made him a great moderator candidate.

“I would say that [our hosts] who are more conservative either live in more liberal cities or towns or they have family/close friends who are left-leaning. They’re more empathetic and understanding because they’re exposed, so they can almost act as translators,” she said. The idea of translation is an intriguing one: in fact, moderators and admins in the MADA Facebook group often spend time negotiating among different perspectives. Mark says one of his roles is to mediate with the group’s conservative members, helping them express themselves more clearly. Sometimes that includes dropping a helpful hint via private Facebook message or stepping into a discussion to draw them out. According to Lisa, who ultimately worked with nearly one hundred individuals, groups, and activists during her time at Facebook, one of the first things MADA did well was “create this role of being a ‘bridger,’ this identity of people who care about this higher, separate purpose.”

Not All Discussions Are Made Equal

Mark said the most challenging subjects for the group have been race, immigration, and abortion. In this, they are not unique. The Facebook group had been live for a little under a year when a member first suggested a poll asking other members when they believed abortion was acceptable. (According to the rules, members can suggest questions, but questions have to be approved by admins to show up on the main MADA discussion page.)

“We thought, ‘Hey, this is a good topic,’ and we just threw it up there,” said Mark. Responses came quickly. Whenever members of the group reply to each other, the moderators get a notification. Watching their notifications come in, Mark said, the moderators realized the discussion might be spinning out of control.

They jumped into the comment thread and posted the following:

Hi everyone! We recognize that this is a potentially very personal and controversial subject for some in the group. Because of that, our group of moderators will spend extra care checking in and moderating the thread. Thanks, [redacted], for the poll. It’s our understanding the idea for this prompt came out of a discussion in another thread last week between [names redacted] on the subject of abortion. Thank you, all, for participating and keeping in mind our ground rules.

Despite jumping in early, Mark says the thread quickly became a “fire out of control.” The moderators eventually closed comments.

Justine also remembers this discussion. It was incredibly difficult for her, and changed her perspective and practice as a moderator. Early on in the conversation, under her own name, she posted:

Are there any women in the group who feel comfortable sharing their thoughts? I want to acknowledge that having this posted by a man and then the first responses being from a few men might make some people feel uncomfortable. When I say some people, I’m including myself.

When they were first developing the in-person dinners, Justine and Tria made a point of clearly defining the facilitator role. They didn’t sit at the table with their guests. They didn’t share their personal views. These practices created a separation between hosts and participants, an acknowledgment that the two groups answered to different goals. Justine defines the duty of a moderator as follows: “Our main goal is for everyone to feel like they’re in a fair, safe environment where they won’t be judged.” She takes this distinction so seriously, she says, that she even tries to moderate the inadvertent expressions that cross her face during a dinner. “We all respond to things we hear. If I feel something rising in my face—I just pull back.”

When opening the Facebook group, she and Tria decided to relax their policy a bit. It was a deliberate departure, influenced by the online format. “We want people to get to know us and the other moderators as contributors, and not just see us as completely neutral robots or rule-enforcers,” she said. By expressing their views, they lent their presence in the group a certain familiarity that might otherwise have been lacking. But it also made it harder to figure out where the line between personal and moderator duty lay.

In the abortion thread, not long after the first post under her own name, she posted again, also under her own name:

Men are certainly important in the equation. At the end of the day, though, I’m not sure it can be disputed that it is women and their bodies who experience the pregnancy. And it still bothers me sometimes to see such strong opinions from men about my and other women’s bodies, even if they perfectly deserve to have those opinions. It might take time to unpack why that might be. My comment was primarily meant to encourage more women to join the conversation.

In thinking back on it, she acknowledged that part of the moderator’s job was moderating her own emotions and expressions online, the same way she moderates her face during an in-person dinner. She’s learned that the boundary isn’t just about particular topics—although certain topics are particularly hard for her—but rather, a matter of her own emotional state:

There are times when I just start typing, and I realize, “Oh, I’m typing very quickly, and I’m typing with a lot of emotion.” Before I hit send I just pause and read it back, edit it, and in that editing, I’m thinking about people [in the group]: how would they interpret what I’m [writing]? What would they interpret as an attack or as an assumption? And so I’ll go back and make edits. And the edits are usually, instead of stating opinions as facts, I’ll add “I believe,” “I think,” “I’ve observed,” “In my experience,” so it’s a little less stating something as though it’s a given. When I’m typing, there’s that moment to pause before hitting send.

Part of the MADA moderators’ philosophy is to reach out to members one-on-one to talk about potential rules infractions, ask about their well-being, and encourage them to moderate the tone of their posts. It’s a slow, challenging process of relationship-building, and Justine often has multiple private messages going at once with members of the group. A member messaged her to say he felt like her comments on the abortion thread seemed like bias and possibly favoritism. She considered the feedback and offered to “do better,” including stepping back from moderating situations where she might have preexisting relationships or a strong personal bias. It was hard for her, though, she says, since she has strong personal views on the subject. The strength of members’ responses indicates the intensity of people’s feelings on the topic, but her private messages demonstrate the extent to which those in moderator roles are often held to different standards from participants, both by themselves and by those in their communities.

In a similar future situation, instead of posting a general statement asking “women” to participate, Justine says she would “tag people who I know might have an opinion and sometimes [those people] are women.” She said she’d also consider stepping back from moderating discussions that she feels deeply attached to personally. Mark says that the moderators now know that discussions on topics like abortion and race need to be tightly focused, and they’ll try to shoot each other a heads-up when approving a question on one of these topics.

Talk Less, Listen More?

Partly in response to discussions like the one above, the moderators proposed an initially controversial new rule, where they asked everyone to limit themselves to one comment per thread per hour. Justine explained that the one-hour rule matches MADA’s in-person dialogic principles. “In person, if there are two people who are dominating the conversation, we would interject. We would let it go for a little bit, there is some magic in people being able to feel what they’re feeling and be able to express it, but when it gets to the point that people aren’t listening, then we interrupt.” The same thing was happening in the rapid-fire, often two-person comment exchanges, she continued, as in those rapid in-person conversations. “It’s happening so fast it’s unclear if they’re even reading what the other person wrote.”

The group had another discussion about abortion not along ago, Mark says, and he feels it went a lot better. A member suggested the following question:

I have a sensitive question on several fronts, but my motivation is not to argue about abortion or religion, but to understand the logic that goes into this position: Many people who hold anti-abortion positions base their positions on Christian scripture (e.g., Jeremiah 1:5; “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you…”) and yet a sizable proportion of anti-abortion position-holders (I don’t have stats) also support certain exceptions, such as when a pregnancy endangers the life of the mother or in cases of rape or incest. I guess I’m wondering how, if you believe some version of the argument of unborn children having inalienable rights or that pregnancy is like the fingerprint of God; a work which is “fearfully and wonderfully made” (Psalm 139:14), how is it also logically consistent to allow for ANY exception, ever? How is the child of rape or incest any less entitled to life than children conceived under other circumstances? Or okay for humans to save an adult woman over a fetus? Or, say, a pregnant 11-year-old girl?—was it not God’s jurisdiction to knit life into these wombs?

The question, Mark says, made sense to post because it tackled the topic but in a detailed and specific way. It came at the topic of abortion from the side, asking for theological justification and ideas, rather than asking people outright whether they believed abortion should be legal.

The member who posted the comment, Jess Thida, said the discussion was civil, but she also found it ultimately unsatisfying. “They [the commenters] did not address specifically what seems to be a logical inconsistency, so there was not a good resolution to that question.” She joined the group more than a year ago. At the time, she was an American living in Cambodia. She didn’t have a lot of American friends around her, and she wanted to talk about politics in a way that went beyond what she saw as the “sensationalism of the media” and the “polarization of my friend group.” Most of her questions—like the one above—are her attempts, she says, to understand points of view she doesn’t agree with. She credited the moderators with making these conversations possible. “It really comes through that [the moderators] just want to create an open dialogue and a comfortable space for everybody to talk.” She enjoys that the group allows people to “connect on a human level without resorting to insults and caricatures.”

To Mark, the abortion discussion qualifies as a victory. “I don’t care who’s right or wrong, but I love that this thread continues for sixty-some people,” he said. He also doesn’t think the purpose of the group is to change people’s point of view. Jess, still a regular participant in MADA conversations, isn’t so sure. She wonders: “Why are we spending all this energy arguing our positions if it’s not changing anyone’s mind?”

Getting Comfortable over Time

After two years together, the tone of the group has started to feel comfortable.

“This is a group of people who have learned how to communicate online. They have a history,” Mark said.

Tria, who describes herself as a sensitive person, says she’s not sure she’d sign up to moderate an online group if it wasn’t MADA. And yet she also noted to me that the community has grown and changed over time. “Our community understands the tone better, and there are more people following and setting that tone.” In a 2019 paper, researchers documented that moderation decisions, over time, “shape community identity.”14 This identity becomes familiar for moderators as well. As the MADA group has established rapport, Tria says, moderation work has become emotionally easier for her.

The group now has close to seven hundred members, and Justine says they’ve thought about capping it. The discussions function well, and according to Facebook’s metrics at the time of this writing, 73 percent of members counted as “active” (a somewhat generous measure that means they’d recently commented, reacted, liked, or even viewed the group’s content). Justine spends a lot of time thinking about how to encourage even wider participation. One of their strategies, she says, has been to vary the tone of the content they post throughout the week. At the beginning of the week, the moderators post more pleasant, “getting to know you” questions, things like “What’s one item on your to-do list that you’ve been putting off?” These questions aren’t political or issue-based, but the answers are often telling. These questions are great for what Justine describes as “the more shy people.”

“That’s an entry point for them and they feel comfortable… it’s harder when it’s an issue and you have to be more vulnerable and share your opinion,” she said. The moderators have experimented with exercises—similar to the paired discussion from in-person dinners—where they asked participants to private message each other in pairs to get to know each other better. In partnership with Lisa Conn (who no longer works at Facebook, but still builds platforms that facilitate online conversations) they’ve also tried larger video conversations, in hopes of experimenting with a more real-time format.

The Online Public Citizen

Unlike the country, neither MADA nor Facebook are democracies, and yet, the work that the MADA moderators do is inextricable from their idea of democracy. Tria described her personal connection to the work:

I think, as the daughter of immigrants, for a long time I felt that outsider feeling… there would be people telling me that I didn’t belong in the definition of patriotic. And I feel that giving so much time and energy to this organization has made me feel like I am contributing to this country.

Mark, meanwhile, turns to history. Since he began moderating MADA, he says he’s started reading up on historical debates and rhetorical strategy, so he can better point out fallacies when they occur in MADA discussions. He admires the relationship between Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, especially the letters they wrote to each other late in their lives, when “they still had reverence for the other person even though they’re political foes.”

The MADA moderators talk frequently about their biases, and about how to acknowledge and address them. The moderators have engaged the group on challenging topics, and have polled members on what subjects to include in or exclude from discussion. At the same time, this particular group doesn’t practice elections: moderators choose other moderators, and there are layers of responsibility even among moderators. Justine and Tria are the only ones who can decide whether someone can join the group. The next moderator tier, which Mark is a part of, includes people who can approve posts that go into the main discussion, while moderators in the third tier tend to the comments but don’t approve members or posts. In this way, the moderator group is its own structured community, with its own rules and practices. They have their own side conversations on Facebook; that’s where they give one another a heads-up before approving a potentially controversial post.

Jess describes the MADA moderation style as “heavy,” and it is. In the time she spent working with Facebook groups, Lisa says she noticed a trend when it came to how much time moderators spent on their groups: “The more active a mod was, the more time they spent in the group, meant that the group was more civil and had better discourse.” She was quick to say that time spent, rather than any particular philosophy, correlated with group civility, but also that defining excellence in moderation was a slippery exercise: “There wasn’t one objective definition we used for a better moderator.”

Jess does perceive the group as being more conservative than liberal. She recently moved back to the United States, and now lives in a suburb of Boston. She describes herself as more centrist than many of her liberal neighbors, and wonders if that isn’t true for her Facebook group, too. “If you were to poll most participants in the group I think you’d find all of us on average are more centrist than the population,” she said. “Because we are open-minded enough to come to the middle to discuss with the opposing side, but if you’re more rigid in your belief system then it’s really hard to find goodness in the other side.”

It’s hard to say whether the group is more centrist than average. Research has shown that both conservatives and liberals tend to perceive partisans—of both parties—as more extreme than they actually are, and themselves as more alone in their centrism than they actually are.15 But the same research also suggests that moderates might not be as prone to that bias as stauncher partisans.16 It’s not inherently surprising that an online political discussion group will attract people who have a higher-than-average interest in political conversation, or that a group dedicated to common ground will be more appealing to those who hold moderate views. Justine and Tria mentioned feeling alienated from or frightened of Trump voters after the 2016 election, but Mark and Jess both describe being intrigued by “the other side” long before they joined MADA. Mark had made efforts to seek out wide-ranging political discussions, attending what he describes as a “drunken philosophy” evening at a local bar. It’s possible that the people who join MADA are more open to political disagreement to begin with, but it’s also possible that the group has shaped and reinforced its own identity over the years.

Surprisingly, who people voted for in 2016—or who they’re voting for in 2020—sometimes seems beside the point. In one recent comment thread, members debated the virtues of an opinion piece by New York Times columnist David Brooks, in which Brooks envisioned an imaginary exchange between a Trump opponent and a Trump supporter.17 An actual exchange, between self-described Trump opponents and supporters, occurred in the comments below the article in MADA. The thread is full of interesting real-life details as to why people voted the way they did, as well as criticism of the way mainstream journalists talk about partisanship.

Acknowledging the group’s spirit of openness shouldn’t obscure how meticulous the MADA moderators are, and how time-consuming their task continues to be. There are very few comment threads—none that I could find—in which a moderator or admin doesn’t make at least one appearance, tending the conversation, watering the seeds of discourse.

In an August 2019 article in the New Yorker, journalist Anna Wiener profiles the two moderators of Hacker News, a tech and start-up-focused online forum. She describes the moderators’ philosophy as “slow.” She doesn’t mean it in a negative way. In fact, she compares the Hacker News moderators favorably to moderators on other community platforms and sites:

On Facebook and YouTube, moderation is often done reactively and anonymously, by teams of overworked contractors; on Reddit, teams of employees purge whole user communities, like surgeons removing tumors. Gackle and Bell, by contrast, practice a personal, focused, and slow approach to moderation, which they see as a conversational act. They treat their community like an encounter group or Esalen workshop; often, they correspond with individual Hacker News readers over e-mail, coaching and encouraging them in long, heartfelt exchanges.18

The MADA moderation philosophy, as expressed to me, seems similar: optimistic in origin and time-consuming in practice. It is “slow” moderation, in that it focuses on individuals and moments. It is conversational, based in shared moments, and it eschews one-size-fits-all categories and descriptions. In order to practice it, in order to believe that the long hours and hard conversations are worth it, the moderators have to believe that they’re making important inroads, or suggesting a blueprint for how we can better approach each other as citizens.

MADA is not alone in their goals or their methods, and looking at other groups in this space suggests some commonalities. Better Angels, an in-person movement dedicated to building bridges across the partisan divide, organizes red-blue workshops where the focus is, according to one of their 2018 papers, “Listening and learning rather than declaring and convincing, with a special emphasis on recognizing and admitting concerns about one’s own side. The goal is not for people to change their minds about issues, but rather to change their minds about each other.” In 2018, Better Angels conducted a survey to understand how participating in these workshops had changed people’s views, and found the following: “About 79 percent of participants report that as a result of the experience they are better able to ‘understand the experiences, feelings, and beliefs of those on the other side of the political spectrum’ and more than 70 percent say that they feel more ‘understood by those on the other side of the political divide.’?”19

Just looking at Justine, Tria, and Mark provides an interesting case study in difference. Mark is gregarious, while Tria is sensitive and Justine is soft-spoken. Their ages and political preferences are fairly wide apart. And yet, what they have in common is a certain personal generosity, evident in their answers to me and to their community. They believe their work is making the world a better place.

From the perspective of creating better citizens, MADA leaves questions unanswered: What happens when groups grow even larger? What about groups where a single arbiter doesn’t enforce entry? And what about actual hate, the belief that some people are better or more worthy of participating in our democracy than others? To these large civic questions, MADA doesn’t necessarily provide a pat answer, nor does it try to. But it does demonstrate how a small cadre of moderators and members created an online space where several people found a little bit more understanding. If that’s your goal, whether on your own private Facebook feed or in a broader discussion, then their model offers some valuable lessons.

Make America Dinner Again

How I Met MADA

I met Justine Lee for the first time in New York. We’d “met” online months before, while working together on a podcast project about Asian American life. I asked her for suggestions for whom to profile in this book; she recommended herself. Over a couple of hours, Justine told me her story. Since October 2017, she and her friend Tria Chang have run a Facebook group called Make America Dinner Again (MADA). The name pokes fun at partisan rhetoric, but the group has a serious purpose: to encourage understanding and dialogue among people with differing political views. Justine and Tria started the group after the 2016 presidential election, and it now has almost seven hundred members. Those who want to join have to apply by answering a few questions on Facebook; the founders read each application thoroughly and personally. As MADA has grown, they’ve accepted new members with an eye toward political balance; Justine says the group today includes roughly equal numbers of self-identified liberals and conservatives, as well as many other perspectives. The two of them, along with nine other moderators, oversee debates about the most divisive political topics in American discourse. Recent posts include one comparing restrictions on gun ownership to restrictions on book ownership, another asking whether or not a Holocaust-denying school principal should have been fired, and a third asking how San Francisco can humanely resolve escalating rates of homelessness.

Their group is part of a growing movement, born in the run-up to and wake of the 2016 presidential election, focused on building bridges across what seems to be an ever-widening political divide. In any given week, the MADA moderators research and post articles for the wider group to discuss, contact group members one-on-one to offer advice on the tone or content of their posts, or—in Justine’s case—read through short surveys filled out by people who want to join the group. But their real work is trying to shore up common ideals in a divided world, building slim but strong bridges across the divide of partisan opinion. Justine refers to this type of work as “translating.” The group is sometimes fractious, sometimes hopeful, and often challenging. But in working there, Justine and Tria have established an interesting online home.

The Lost Art of the Dinner Party

MADA grew out of Justine and Tria’s feelings about the 2016 election. A self-described political liberal living in San Francisco, Justine says she woke up in a daze the day after Donald J. Trump was elected president. She didn’t know how to respond. She wasn’t alone: liberals across the country were torn and dismayed. In a popular blog post written right after the election, political science professor Peter Levine outlined several potential responses that the left could make. These possible responses included things like “winning the next election,” “resisting the administration,” and “reforming politics.” They also included “repairing the civic fabric” via “dialog across partisan divides.”1 This last category is the one that Justine and Tria would come to belong to.

Justine had just finished a public radio internship, which had exposed her to local politics. But she’d found politics to be “inaccessible and a little overwhelming.” Instead she enjoyed the “human stories,” in part because “I’ve always believed that there are multiple sides to a story.” That curiosity about other people, and a focus on the human face of political debates, would become the core principles of MADA.

“Dialog across partisan divides” sounds great in theory, but is difficult in practice. In a June 2016 study by the Pew Research Center, nearly half of self-identified Republicans and Democrats said they found discussing politics with someone with opposing political views to be “stressful and frustrating,” and more than half said that they left such conversations feeling like they had less in common than they originally thought.2 Maybe just as troubling, at least from a national unity perspective, was that Republicans and Democrats saw each other in a personally poor light, ascribing negative qualities like laziness or closed-mindedness to those on the other side of the political divide.3 Researchers refer to this type of partisan dislike as “affective polarization.” In a seminal 2012 paper, the researchers Shanto Iyengar, Gaurav Sood, and Yphtach Lelkes demonstrated that affective polarization in the United States had risen dramatically since 1988, as measured by things like whether or not people would be upset if their child married someone from a different political party. In another paper, published in 2019, a group of researchers suggested that affective polarization could have serious consequences: “Partisanship appears to now compromise the norms and standards we apply to our elected representatives, and even leads partisans to call into question the legitimacy of election results, both of which threaten the very foundations of representative democracy.”4

In the months before the election, Justine says she saw political conversations break down, time and again, in her own social media feeds. People often talked past each other.

“Anytime there was a news article posted on our FB feeds, we would see it in the comments. People would make a statement in response to the headline. They would come out really strong, with almost no room for dialogue.” The worst, she says, were the comment sections on news organizations like Fox News or CNN, which she says turned into a “a mass of name-calling and trolling and inflammatory language.”

Platforms like Facebook had enormous reach and scale, but neither their technology nor their business models prioritized the facilitation of wide-ranging conversations. On the contrary, algorithms that powered popular social media sites often encouraged like-minded bubbles. A popular Wall Street Journal project from the time, called Blue Feed, Red Feed, compared how liberal and conservative Facebook news feeds featured different stories, from different outlets, with different slants.5 “If you wanted to widen your perspective and see things from a broad range of backgrounds, you would have to go and like the pages yourself. Facebook’s product makes it hard to do this,” Jon Keegan, the project’s creator, told media industry site NiemanLab in May 2016.6

But there was a flip side to the name-calling: entirely homogeneous spaces where people never interacted with anyone who had opposing views.

“If it was something that was posted on our friends’ feeds… everyone was in agreement, but it almost felt narrower still,” Justine said.

She recruited her friend Tria Chang, a wedding planner who also lived in San Francisco, to host a dinner party for people with opposing political views. Their hope was that under the auspices of a shared meal, Democrats and Republicans might discover even more common ground.

Tria already had experience with unusually tense events—weddings, she says, “are more complex than people” imagine. A lot of the tension at weddings lives beneath the surface—in part because people repress the “negative but natural emotions” that they might have about, say, a friend getting married and leaving them behind, or a child embarking on a new and independent life stage. A party among people with different political views can feel the same way: barely comfortable, and then only if people skirt the issues they really care about. Justine and Tria wanted to bring these sources of tension to the surface, and in talking about them, try to make people more comfortable with hard conversations. Doing it within the safe and familiar ritual of dinnertime would, they hoped, make participants feel more secure.

“We’re sharing a meal together, there’s already this understanding that we’re all coming with good intentions,” said Justine about the choice.

The dinner party carries a lot of weight as a symbol and stand-in for social life. In the bestselling 2000 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, political scientist Robert D. Putnam traces several contributing factors in the decline of American civic engagement over the past several decades. He spends a lot of time talking about the dinner party, noting that “Americans are spending a lot less time breaking bread with friends than we did twenty or thirty years ago.”7 In the ancient world, it was a deep and unpardonable offense to break bread with someone and then betray that hospitality, either in word or deed. Texts from the Odyssey to the Bible describe the dreadful character of—and dire consequences for—ungrateful guests. The ritual of dinner runs deep in our blood, certainly deeper than partisan divides. “Food can act as a conversation starter, but also as a buffer, in some way. If there’s nothing to talk about, if it’s awkward or uncomfortable, you can talk about the food in front of you,” Justine said. She grew up cooking with her family, while Tria organized dinner parties for a living. They liked the in-person element of a dinner, characterized by long and deep discussion—the opposite of the impersonal, quick-take attack culture they saw online.

If the idea of a brief conversation with a political opponent raises most people’s hackles, a structured three-hour dinner probably sounds like torture. Justine and Tria’s initial idea attracted resistance from both conservatives and liberals, Justine says. Activist friends preferred to focus on direct action in response to the election. The two of them knew very few conservatives, so they took out Facebook ads to try to recruit some. The ads, featuring what they thought was an appealing photo and a fun message, backfired. Conservatives—the minority in deeply liberal San Francisco—feared that the dinner invitation might be a ploy to expose or humiliate them. They also had no idea who Justine and Tria were—after all, relationships are built on trust, and Justine and Tria had yet to build any among San Francisco’s conservative population.

The women soon realized that one of the first things they would have to do was “humanize” the people on the other side of the voting divide, including to themselves. After the election, Tria says she was briefly afraid to leave the house. She associated Trump with sexism and racism, and as a woman of color, she says she felt personally targeted by all the votes that had been cast for Trump. She “felt this fear brewing in me, and I know that fear can quickly turn to hate and I didn’t want to be walking around filled with hate because that would be… unhealthy for… my community.” In order to build bridges, Tria had to step away from that sense of fear, toward a sense of optimism and openness. They eventually recruited some conservative guests through their wider social network instead. They asked each potential participant to answer a few brief questions in order to get a sense of their goals and discussion style. As the day for their first dinner party neared, they began to think about how they, as the facilitators, could help their guests reach this same attitude of openness and optimism.

They also attended to logistics. Pizza felt like a familiar and neutral food choice, and they chose a restaurant in downtown San Francisco that was easily accessible via transit. On a drizzly weeknight in January, they opened the doors. When attendees made their way to the restaurant’s private room, they found special printed menus waiting for them, as well as dice and kazoos laid out on the tables.

The dice were part of an introductory game. Each side of a die corresponded to a question that attendees could ask each other. Questions included things like “Who in your life has influenced you the most?” and, appropriately for the venue, “Given the choice of anyone in the world, who would you want as a dinner guest?” The kazoos were to keep things comfortable: if guests needed a moderator to intervene in the discussion, they could toot the kazoo to get Justine or Tria’s attention.

Justine and Tria planned the evening down to the minute, even going so far as to write out instructions and dialogue for themselves in a detailed “run of show” document. The first part of the dinner, right after people arrived, was a time for “softball questions,” things like “Where are you from?” and “What made you interested in coming to dinner tonight?” Justine and Tria wrote down the following advice for themselves, the moderators:

Give each speaker our totally absorbed and undivided attention and empathy, whatever they’re saying. Some “heavy talkers” will need to be interrupted. Some more shy folks will need to be drawn out. That’s our main job, to ensure that a diverse range of speakers are heard and to perhaps offer a comment or insight here or there.

The document offers a clear perspective on both their strategy and their priorities: for example, they rank communication and listening above changing people’s minds. (In fact, the idea of changing people’s minds doesn’t appear as a goal anywhere in the document, or really, in their moderation philosophy.)

After the softball questions, the group paired off to get to know each other better. They talked about whom they’d voted for in the recent election and why. Afterward, for the final half hour of the dinner, the group came together to discuss more sensitive matters. Justine and Tria wrote down questions like:

- How do you feel about large-scale protests like the Women’s March on Washington, set to occur after the inauguration? Do you think they are useful; if so, what do you think they can or will accomplish?

- How do you feel about the likely congressional repeal of the ACA? Will it affect you personally in any way? If so, how?

At the end of the dinner, the moderators passed around sticky notes. People wrote down their hopes and dreams for the country. They put their sticky notes up on a wall, and found points of similarity and difference.

The group ended up discussing only three of the scripted questions. Once lubricated with drinks and food, guests found their own rhythm and the conversation never lagged. At the end, when it came time to share hopes and dreams, the group found several points of commonality, including a dislike for the way the media had covered the most recent election, and a hope for more support for the middle class under the new president.

Reducing partisan distrust is difficult because it’s hard to pinpoint what exactly causes this type of distrust, and also because political identity is complex and interacts with many other aspects of self. Nonetheless, research has suggested that focusing on similarities instead of differences—like Justine and Tria did with their Post-it Note exercise—can help.8 Both liberals and conservatives tend to overestimate the extremity of other people’s political views, even within their own party, so gatherings that bring together those with more moderate views could help counteract that bias.9

Justine and Tria went home exhausted, but also hopeful. Justine felt that the evening provided a powerful counter-response to their critics. It was “just a… gathering at the end of the day,” she acknowledged, but “it is possible.”

They didn’t plan to repeat the dinner for several months. But a journalist who attended the first dinner wrote a story that ran on National Public Radio. Production companies and journalists reached out to Justine and Tria to organize more dinners, and they got emails from interested participants and hosts all over the country. What began as a one-off dinner grew into a series, and eventually into a network, with chapters in several major cities, each chapter headed by a local organizer. But their concept remained emphatically in-person, among co-located participants, until later in 2017.

The Opposite of the Comments Section

It’s not hard to find examples of online political discussions run amok. When Lisa Conn joined Facebook as an employee in the summer of 2017, she wanted to find examples of the opposite: online political discussions that had helped people learn and find common ground. Before joining Facebook, she was a product manager at the MIT Media Lab and worked on a project that tracked how people talked about politics, elections, and policy on Twitter. Like others doing similar work around the country, she and her colleagues found that social media—in theory, a powerful tool for creating community—could also create closed networks of conversation among like-minded people. “Giving the world power to build communities doesn’t necessarily bring the world closer together,” she said. “Building communities can actually tear the world apart, by limiting people’s contact with those who have opposing views.”

It was a finding that Facebook’s leadership had begun to appreciate as well, as they tried to figure out the role that Facebook should play in society. The company had started to receive complaints that its platform and algorithms didn’t do enough to protect users’ privacy or halt the spread of misinformation. News reports had surfaced that Cambridge Analytica, an election data firm based in the UK, had accessed millions of Facebook users’ personal data without consent, and used this information to help conservative politicians get elected.10 All of these things presented serious challenges for Facebook’s platform and philosophy. In 2017, the company changed its mission statement from “Making the world more open and connected” to “Give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together,” a shift toward actively promoting cohesion.11 In a video interview with CNN Tech, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg described the company’s new mission: “Our society is still very divided, and that means that people need to work proactively to help bring people closer together.”12

Lisa, who proudly says her grandmother was a civil rights activist, wanted to know if, through active and thoughtful moderation, online spaces could be made to do the opposite of what her research team had observed at MIT. Could online discussions encourage dialogue among people with diverging views? Despite what she describes as a lack of popular trust in the Facebook brand at the time, she was “genuinely concerned about the ways in which extremism and polarization were flourishing in social media.” Her goal was to identify possible improvements to Facebook’s Groups feature, by learning from people who were bridging gaps and fighting polarization. Soon after she started at Facebook, she met Justine and Tria through a colleague.

At the time, MADA was still an in-person group. The three of them talked about whether there could be a way to extend the MADA philosophy into a Facebook group format. Justine and Tria had hesitations. After all, they’d formed MADA as a counter-response to the impersonal, attack-driven culture they saw in their own social media feeds. Many of the dinner’s focal moments involved participants looking into one another’s eyes and responding to one another in real time. These types of conversations give people plenty of chances to observe what researchers refer to as “symbolic cues”—a wink, a shrug, a sigh—that can be just as telling as their actual words.13 Justine and Tria considered the act of paying attention to others’ symbolic cues part of the “humanization” process. That level of context gets lost online, when people don’t always know each other’s real names, don’t see nonverbal cues, and can enter and leave conversations without notice.

But an online group offered benefits, too—including scale, reach, and potential longevity. Justine and Tria were already facing challenges as MADA grew. The first was geography—they didn’t have enough hosts to meet demand, especially in less densely populated areas. Second, they wanted to capture the energy and enthusiasm that participants felt after a dinner by giving them a place to keep the conversation going, but that wasn’t always an option in physical space.

They perceived other benefits, also. There are plenty of people for whom an in-person dinner is not accessible, because of temperament, ability, or other reasons, but an online group might be. Among online platforms, Facebook had enormous scale and ubiquity, as well as tools for groups that would, in theory, give moderators greater control and agency in guiding conversation. With careful, thoughtful, and diligent moderation, perhaps an online version of MADA could help keep the spirit of the project alive.

They gave the same careful treatment to their online moderation practices that they had to their offline moderation. Several weeks before launching the Facebook group, Justine, Tria, and Lisa drew up a three-column spreadsheet identifying eleven top-level MADA “goals.” These included things like “give people the agency to ask for help,” “show that people’s views are complex,” and “connect people 1:1 after the dinner.” In the next column of the spreadsheet, they listed how MADA achieved each of these goals through in-person moderation practices. For example, at an in-person dinner, participants got noisemakers—like the kazoos from the first dinner—or a set of red and green cards that they could hold up to show the moderators that they needed help or felt uncomfortable.

In the third column, the three brainstormed ways to achieve these same goals in the Facebook group. For example, they proposed “green/yellow/red emoji” and a “bell emoji” as ways participants could indicate discomfort or get moderators’ attention. To help people show a variety of views, they suggested “create a poll with multiple answers,” and to build one-to-one connections, they considered “encourage friending.”

They built the group slowly over time, trying to maintain a balance of political perspectives. Just like the in-person dinners, they asked everyone who wanted to join to answer a few initial questions. In reviewing hopeful participants’ answers, Justine often also looked at the person’s public Facebook profile to get a sense of how they expressed themselves online.

Some of these ideas worked better than others. The bell emoji, for example, never quite took off. Instead, Justine says, they noticed that other members of the group started stepping into heated discussions to remind participants of the rules. As the group expanded, Justine and Tria began to approach some of these extra-helpful members as potential moderators. This is one way to expand a moderation team—by offering additional responsibility to people who are already informally taking on work.

Mark Fosdal was one of those people. He’s in his fifties, grew up in the Midwest, and describes himself as “conservative and a Christian.” He discovered MADA while trying to enhance his social life.

“I had a lot of bad online dates where you sit there with nothing to talk about,” he said, describing himself as the type who enjoys “discussing over dinner [more] than going out to the clubs.” He found a MADA listing on Meetup and attended his first dinner in the basement of a church in Seattle. He remembers a crowd of twenty to thirty people. They started with small exercises that turned into a larger group discussion. He attended another in-person MADA dinner at a private home, a smaller event that he says was more of a “structured discussion” and “controlled environment.” At these first few dinners, he got a sense of “the different flavors” that different hosts brought to MADA, but also saw that the group was united around a “similar theme of sitting down, listening.” Drawn in by the in-depth discussions he was having, he decided to host his own dinner for ten to eleven people.

For Mark, who says he loves conversation but is also an introvert, the MADA dinners provided not just a social outlet but also an avenue for expression and community. Many of his friends didn’t share his conservative leanings. “For the past several years in the Pacific Northwest, there’s an unspoken opinion that you keep your opinions to yourself if you fall into that category.” The group gave him a chance not only to express his own views but to challenge them. He says he left his first dinner feeling “excited, not alone.”

He went to a few more in-person dinners before he found the MADA Facebook page and started contributing there. He eventually started an in-person MADA chapter in his hometown of Bellevue, Washington, and became a moderator of the online group. “I think I stood out in having a point of view and being curious at the same time,” he said. The fact that he had friends with different political views, Justine says, made him a great moderator candidate.

“I would say that [our hosts] who are more conservative either live in more liberal cities or towns or they have family/close friends who are left-leaning. They’re more empathetic and understanding because they’re exposed, so they can almost act as translators,” she said. The idea of translation is an intriguing one: in fact, moderators and admins in the MADA Facebook group often spend time negotiating among different perspectives. Mark says one of his roles is to mediate with the group’s conservative members, helping them express themselves more clearly. Sometimes that includes dropping a helpful hint via private Facebook message or stepping into a discussion to draw them out. According to Lisa, who ultimately worked with nearly one hundred individuals, groups, and activists during her time at Facebook, one of the first things MADA did well was “create this role of being a ‘bridger,’ this identity of people who care about this higher, separate purpose.”

Not All Discussions Are Made Equal

Mark said the most challenging subjects for the group have been race, immigration, and abortion. In this, they are not unique. The Facebook group had been live for a little under a year when a member first suggested a poll asking other members when they believed abortion was acceptable. (According to the rules, members can suggest questions, but questions have to be approved by admins to show up on the main MADA discussion page.)

“We thought, ‘Hey, this is a good topic,’ and we just threw it up there,” said Mark. Responses came quickly. Whenever members of the group reply to each other, the moderators get a notification. Watching their notifications come in, Mark said, the moderators realized the discussion might be spinning out of control.

They jumped into the comment thread and posted the following:

Hi everyone! We recognize that this is a potentially very personal and controversial subject for some in the group. Because of that, our group of moderators will spend extra care checking in and moderating the thread. Thanks, [redacted], for the poll. It’s our understanding the idea for this prompt came out of a discussion in another thread last week between [names redacted] on the subject of abortion. Thank you, all, for participating and keeping in mind our ground rules.

Despite jumping in early, Mark says the thread quickly became a “fire out of control.” The moderators eventually closed comments.

Justine also remembers this discussion. It was incredibly difficult for her, and changed her perspective and practice as a moderator. Early on in the conversation, under her own name, she posted:

Are there any women in the group who feel comfortable sharing their thoughts? I want to acknowledge that having this posted by a man and then the first responses being from a few men might make some people feel uncomfortable. When I say some people, I’m including myself.

When they were first developing the in-person dinners, Justine and Tria made a point of clearly defining the facilitator role. They didn’t sit at the table with their guests. They didn’t share their personal views. These practices created a separation between hosts and participants, an acknowledgment that the two groups answered to different goals. Justine defines the duty of a moderator as follows: “Our main goal is for everyone to feel like they’re in a fair, safe environment where they won’t be judged.” She takes this distinction so seriously, she says, that she even tries to moderate the inadvertent expressions that cross her face during a dinner. “We all respond to things we hear. If I feel something rising in my face—I just pull back.”

When opening the Facebook group, she and Tria decided to relax their policy a bit. It was a deliberate departure, influenced by the online format. “We want people to get to know us and the other moderators as contributors, and not just see us as completely neutral robots or rule-enforcers,” she said. By expressing their views, they lent their presence in the group a certain familiarity that might otherwise have been lacking. But it also made it harder to figure out where the line between personal and moderator duty lay.

In the abortion thread, not long after the first post under her own name, she posted again, also under her own name: