Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

Building a start-up is like being thrust into the middle of the Amazon rainforest: living every day on the edge of your comfort zone, vulnerable to the unexpected challenges constantly being thrown your way, and constantly shifting to meet daily demands and do everything and anything you can to survive, let alone thrive.

Vulnerable, raw, and deeply transparent, Fully Alive reveals powerful tools and lessons that can teach all of us how to grow toward and beyond our personal edges, no matter our circumstances.

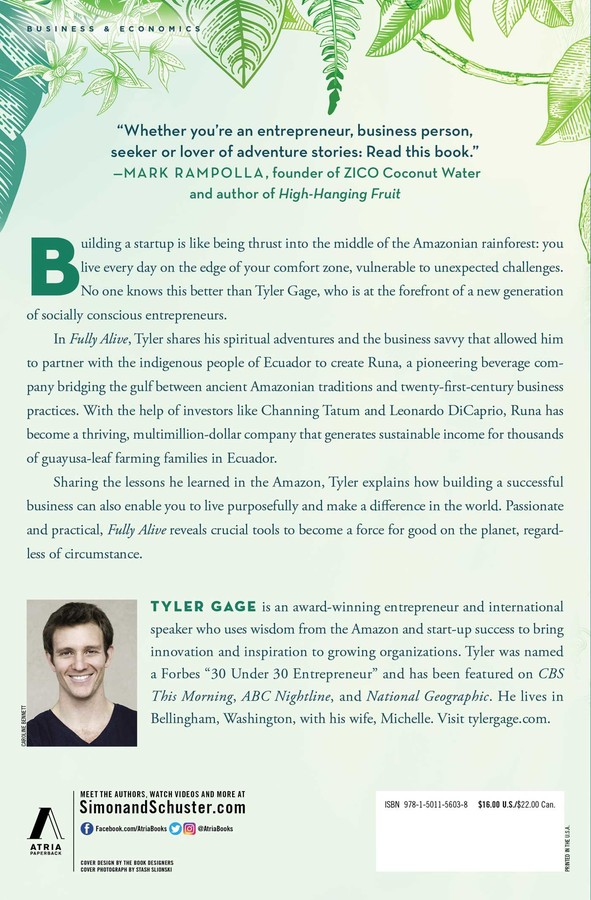

Tyler Gage shares his spiritual adventures and the business savvy that helped him create RUNA, a pioneering organization that weaves together the seemingly divergent worlds of Amazonian traditions and modern business, demonstrating how we can dig deeper to bring greater meaning and purpose to our personal and professional pursuits.

From suburban youth to immersion in the Amazon to entrepreneurial success, Tyler’s journey clearly shows that passion and opportunity can be found in the most unexpected places. Captivated by a rare Amazonian tea leaf called guayusa that had never been commercially produced, Tyler started RUNA to partner with the indigenous people of Ecuador to share its energy and its message with the world.

Using the spiritual teachings, lessons, and healing traditions of the Amazon as his guide, Tyler built RUNA from a scrappy start-up into a thriving, multimillion-dollar company that has become one of the fastest-growing beverage companies in the United States. With the help of investors such as Channing Tatum, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Olivia Wilde, RUNA has created a sustainable source of income for more than 3,000 farming families in Ecuador who sustainably grow guayusa in the rainforest. Simultaneously, RUNA has built a rapidly scaling nonprofit organization that is working to create a new future for trade in the Amazon based on respectful exchange and healing, not exploitation and greed.

Practical tools and lessons are woven throughout the story of Gage’s successes and failures, offering guidance on how to relate to obstacles as teachers and how to accomplish our personal and professional goals in the often uncertain circumstances we find ourselves in.

Excerpt

I arrived back at Brown shortly before the fall semester of 2008 to spend some time with two of my best friends, Nat and Pat. Nat, also of Quaker descent, had spent the summer working for a clean technology investment fund in Thailand, and Pat had biked 1,500 miles across Laos, Burma, and Thailand. Every time I returned to Providence, I felt disconnected and questioned why I had come back, but sharing tales of misadventure and discovery with my friends always provided a reassuring bridge.

As we hiked through Lincoln Woods just north of the city, the conversation became very “Brown” as Nat and Pat plotted a variety of seemingly high-minded business ideas called “social enterprises” that they wanted to launch after graduation.

“So, social enterprise,” I asked. “Is that, like, a thing?”

“Yeah, dude,” Pat said. “It’s social entrepreneurship: basically, the idea that business can be used as a tool for social good by trying to find innovative methods to solve environmental or social problems in ways that nonprofits or governments suck at.”

My wheels started turning.

Pat continued: “There’s an economist from Bangladesh, Muhammad Yunus, who started something called Grameen Bank, which gives loans to poor people who wouldn’t normally qualify. He pretty much began the whole thing. I have a book that talks about him and other social entrepreneurs I’ll give you when we get back to the house.”

Later that day he handed me How to Change the World: Social Entrepreneurs and the Power of New Ideas by David Bornstein, which tells the stories of social entrepreneurs from around the world. I started it at about 10:00 p.m. that night and finished by 5:00 the next morning, unable to put it down. After every chapter I couldn’t help but reflect on the challenges I’d seen in the Amazon: the deforestation in an endless quest for hard currency, the encroachment of oil companies ever farther into the jungle, the almost impossible tightrope walked by indigenous people who wanted to preserve their traditions but also have a foot in the modern world.

Over the last few years I’d run across numerous well-intentioned nonprofits that had high hopes for saving the Amazon. Each was trying to work with local communities to protect their culture and the environment, using a variety of tactics from ecotourism, to planting some hot new commodity crop, to this nebulous concept they called “capacity building” that I could never fully wrap my head around. Unfortunately, when the tourists never showed and the global price of coffee plunged, the indigenous communities were left holding the bag.

The common denominator seemed to be that the nonprofits hadn’t thought through the potential markets for the products or services they were promoting, nor had they taken a rigorous business approach to make sure that each project was actually . . . well, sustainable in the truest sense of the word. This social enterprise concept seemed to address some of the shortcomings of the nonprofit approach and offered me a totally new way of thinking about how you can try and make a difference.

An Energy Drink?

Brown has a “shopping period” during which you can sample classes at the start of each semester. On the first day of school I went to check out a class on social entrepreneurship that Nat had mentioned to me. My good friends Charlie Harding and Dan MacCombie were also shopping the class. When it finished, they were both heading to another business course, something called Entrepreneurship & New Ventures. It was going to be a hands-on course about building a business from the ground up. They said I should come.

My college coursework up to this point had included not a single math, science, or business class; instead, I tended to take courses like Ecopoetics, or Witchcraft in the Middle Ages—interesting, for sure, but not exactly the foundation of many thriving capitalists. I thought the social entrepreneurship class would be plenty for me, but Charlie and Dan persisted. Aden Van Noppen and Laura Thompson, two of our good friends who were also interested in international development, were also taking it, they said, and the professor was supposed to be great. I relented and decided to skip going to yoga to join them.

Danny Warshay, a successful serial entrepreneur who had cofounded and sold start-ups to companies such as Apple, was teaching the class. He told us he was going to lead the course in the style of a Harvard Business School seminar, with a focus on the practical nuts and bolts of getting a company from idea to execution. In addition to reviewing case studies in every class, the backbone for the semester would be the creation of a business plan, working in small teams to create the idea, write the plan, and then pitch it as the final.

Danny came across as such a caring, knowledgeable, and focused teacher that I forgot all my reservations about taking too many business classes and instead felt a blast of enthusiasm. The newness of the language, tone, and types of students in the class also intrigued me. I saw it as another form of cultural exploration.

Charlie, Dan, Aden, Laura, and I formed a group. We all knew each other and were friends to varying degrees. Dan and I had met the first week of freshman year (although neither one of us can remember exactly how or where, which indicates the state of mind we were probably in when we met). Charlie was a year behind us, but the three of us had all gotten close the year before in yet another quintessentially Brown class called Introduction to Contemplative Studies, in which our lab work was to meditate.

Our newly formed team came up with some really dubious business ideas over the following weeks, including an automated payment system for parking on campus, and a Fair Trade café and showroom concept. Charlie had an idea to somehow create a validation system–driver’s license type thing for hitchhikers to make ridesharing easier and safer. I thought it was a terrible idea. Three months later Uber was founded with a perfect solution to essentially the same problem, just approached from the driver’s side and not the traveler’s side.

At the time I was trading emails with a friend in California named Jonnah. We’d hit it off after we were introduced through mutual friends over our shared interest in South America. A sweet, thoughtful, spiritually inclined guy, he had developed a passion for guayusa, the tea that I first drank in Costa Rica with Joe. Jonnah had spent time in Ecuador with an indigenous family learning more deeply about guayusa’s roots. He wanted to work with that family to import and sell guayusa tea in the U.S.

I wasn’t surprised by his idea. In addition to Jonnah and Joe, I had met several other people throughout my time in South America who toyed with the idea of selling guayusa in the U.S. It was an appealing concept: the tea tastes great, gives you an uncommon boost of energy, and has a deep connection to the roots of Amazonian spirituality.

The major complication was that no one had ever commercially produced guayusa. The only ways to buy guayusa at that point were from an artisans’ market in Ecuador that sold piles of whole, dried leaves; from a small Ecuadorian tea company that offered a rinky-dink tea bag product; or from a few sketchy websites that sold dirty milled leaves in Ziploc bags. This meant that anyone looking to get into the far-from-burgeoning guayusa business in a serious way would have to build an entire supply chain from scratch. Not an easy task by any means, and especially hard if you were something of a hippie, as was the case of almost everyone interested in selling guayusa in the U.S. (myself included).

Given that we were having a hard time coming up with a good idea for our class, I suggested to the group that we write a business plan for Jonnah and give it to him at the end of the semester to run with. Everyone agreed.

Following Jonnah’s lead, our first idea was simple: work with a few indigenous families in Ecuador who would farm the guayusa that we would then sell out of a loose-leaf tea house. Danny shook his head when we ran it by him. “Think bigger!” he ordered. Our plan, he said, sounded like a lot of work to sell a few thousand dollars’ worth of tea every month. He was hyper-focused on challenging his students to craft ideas that could be scaled into large businesses.

Crammed late at night in a tiny conference room at the SciLi, one of Brown’s main libraries, we brainstormed.

“Guys, what if we made a powdered guayusa product, put it in little white packets that said in big letters, ‘DO NOT SNORT THIS,’ and sold it on college campuses? It would crush it!” Dan joked.

“We can have different flavors, like Coco-Caine and MDMAango!” Laura said, running with it.

“THChocolate!” Charlie added, not missing a beat.

“Good morning, Mr. Venture Capitalist,” Aden said, as if she was making a pitch. “Our company makes ‘nasal’ energy drinks inspired by hard-core drugs . . . riiiiiight.”

Maybe it wasn’t so far-fetched, since Four Loko, an energy drink with high amounts of caffeine, alcohol, and wormwood (the main ingredient in absinthe), was an underground success at the time—though it would soon be outlawed in several states.

“What about just making an actual energy drink?” Charlie asked.

“Sure,” I laughed, thinking of aggressively in-your-face brands such as Red Bull and Monster. “That sounds like a really high-integrity social enterprise.”

The rest of the group was silent, though, thinking it over. I backtracked a little. “I guess an energy drink that was actually good for you and really helps people would be something new, but isn’t the idea of a healthy energy drink basically an oxymoron?”

I’d drunk a total of two Red Bulls, and both times were two of the worst nights of my life (longer stories there). As someone whose usual liquid consumption revolved around massive amounts of herbal teas such as turmeric, ginseng, hibiscus, and tulsi, consuming chemicals such as acesulfame potassium, Creatyl-L-Glutamine, and calcium disodium didn’t go over too well with my body. And it certainly wasn’t a product I would want to take to the market.

We did a quick Google search for “energy drinks” and one of the first images that came up was an ad that featured a zoomed-in picture of a woman’s butt à la “I like big butts and I cannot lie” with a can of Monster attached to her hip, held in place by a G-string.

“Welcome to the world of energy drinks,” Aden quipped.

However, a little further research revealed that we actually might be onto something: approximately $3.2 billion of energy drinks were sold in the U.S. in 2008, and the market was forecasted to grow 25 percent annually. Even better, it turned out that the other segment of the beverage industry that happened to be growing exponentially was . . . tea. Specifically, ready-to-drink teas sold in bottles and cans.

To round things out, our idea also hit the other trend sweeping the world of consumer packaged goods: we had a product with an authentic story that was organic, healthy, and made from simple and novel ingredients. As one market research report we read noted: “The major trend across all beverage categories is a new focus on the inherent goodness of a product.”

Danny’s reaction when we ran the idea by him? “That’s it!”

He was fond of citing Doug Hall, an author, entrepreneur, and consultant, who says you should identify three things when you’re thinking about starting a business: the first is the overt benefit your product offers; the second is that you must offer people a real reason to believe; the third is that there has to be a dramatic difference from other products on the market. If you start a business without knowing where you stand on all three of these criteria, you may succeed, but it will be much, much harder.

We’d hit all three, Danny said. We had a leaf with high amounts of caffeine that also tastes great—our overt benefit. The fact that the indigenous communities had used this leaf for thousands of years and that each sale of our drink would give them economic alternatives to cutting down the rainforest was a real reason to believe. And, finally, we would have the simplest, most natural ingredients of any energy drink on the market, which was our dramatic difference.

Our enthusiasm swelled as we spent more and more time on the project and many of the pieces started to fall into place. Like many of the rabbit holes I’ve launched down in my life, I can’t say my head understood what was going on, but in retrospect my heart definitely did. It took a while before I stopped to think about why Charlie and I started staying up most nights until 3:00 a.m. working on the business plan; why I stopped paying attention in my Ecopoetics class so I could finish reading about supply chain innovations at Pepsi; why I started drinking about a gallon of this stuff a day; why my ruminations and research of Amazonian plants shifted from esoteric healing plants like ajo sacha to things like rubber, chocolate, and soy.

I’d learned a shamanic belief that it is possible to invoke and pull different realities closer to you via techniques such as meditation and prayer. In other words, as we make our intentions explicit, we work to bring them into the world. The deeper we dove into this crazy guayusa dream, the closer I could feel its future potential.

Danny recognized our growing dedication and nudged us even further. He introduced us to Bob Burke, the former VP of sales for Stonyfield Farm yogurt, one of the first successful large-scale organic food companies. Charlie, Dan, and I drove up to Bob’s home in Massachusetts to brew him some guayusa and get his take on our idea.

Bob, with his sharp, professorial manner, heard our pitch before responding. “This product is perfect for where this industry is going,” he said. “Organic, sustainable, healthy products with good stories are exactly where the opportunity is. You guys could really have something here. But beverages are tough. Really, really tough.”

Encouraged by his response overall—focusing more on the “really have something here” comment over the “really, really tough” part—we decided to go to the Natural Products Expo East trade show, a yearly gathering where hundreds of natural foods companies showcase their products for store buyers from across the country. The expo is not open to the public, so we posed as buyers for the Brown student café to get in. (I don’t recommend subterfuge, but sometimes you have to improvise). Dan, Charlie, and I walked around gorging ourselves on samples of gluten-free cookies, almond milk, açaí juice, vegan protein powder, and these new coconut water drinks we hadn’t seen before. (This was just before coconut water became “a thing.”)

To our delight, we found that most of the companies brought far too much product with them for sampling and had no desire to haul it back, so we spent the last hour of the show loading Dan’s car with crates of olive oil, vegan chocolate bars, organic blue corn tortilla chips, and everything in between. We did learn a handful of useful insights about key distributors and the challenges of getting new products on stores shelves, but our main takeaway was the simple pervasive positivity shared by these companies putting good, healthy products into the world.

As the end of the semester loomed, we deliriously worked on the business plan. Our final exam for Danny’s course was to pitch an actual venture capitalist whom Danny invited to the class. Different VCs would come each year and Danny warned us, “Sometimes they are passive, but others can be really aggressive. Usually depends how well they slept. So be ready either way.”

We stayed up nearly the whole night before the exam to hone and polish our presentation. As a result, I slept through the final exam for my social entrepreneurship class early the next morning and ended up failing the final. Ironic, I know. We walked into Danny’s class as jittery as a sports team before a championship game. The venture capitalist he’d invited was from a big firm in Boston, and he sat in the front of the room in his suit and tie. It was like Shark Tank but without the famous rich people as judges.

Thirty seconds into the first group’s presentation, the VC broke in. “What data sources did you use to confirm the size of this market?” he asked. As they stumbled to answer, he cut them off again. “I’m really just trying to assess what exactly the quantifiable market opportunity is here.”

From there he interrupted about every thirty seconds with more questions. “Have you researched competitive patents for this type of product and the underlying tech?” This same degree of scrutiny and hard-core interruption also happened to the group that followed. Now our turn. We were terrified.

When thirty seconds passed and then a minute without a peep from the guy, I think we all assumed he was just gearing up for a swift, fatal punch. Finally, a minute and a half in, he spoke up.

“Excuse me,” he said. Big gulps across the board from our team. “How do you all know each other?”

Of all the possible inquiries we’d prepped for, this was not on the list.

“Uh,” I stammered, “We’ve all been friends in one way or another for quite a while . . . sir.”

“Well,” he said, “I can see you guys have a really special energy, a really good feeling between your team. Please continue.”

“Uh, OK.”

We carried on, a little bewildered, as the VC listened in silence. At the end he told us, “As you guys know, the beverage industry is really competitive. I invested in Sobe and that was a big success but a ton of work. You guys have a great idea, and I love that you’re trying to help people. I wish you the best of luck.”

We emerged from the classroom in a daze. We’d expected to get grilled, to be told we were fools and that our plan was laughable. Instead, the message was . . . Go for it? As if we actually were going to do this?

The Invisible Speaks Back

Laura had a semester left in school but already had a job lined up with Google, so she was out. Aden had recently been offered a job with Acumen Fund, a prestigious impact investing fund in New York City. Charlie and I were the ones who had latched onto the idea most, spending hours on end in my apartment brainstorming crazy business models and chugging guayusa. He was passionate about the idea but had a full year left in school and did not want to drop out. Dan and I, on the other hand, were both about to graduate in a few weeks during the mid-year graduation ceremony. Maybe, we thought, we could give it a go with Jonnah?

The decision making was complicated by the fact that Dan and I both had other desirable options. Dan had a final job interview with McKinsey the consulting firm; I had some grant opportunities to return to Peru to record, translate, and help preserve Shipibo songs. Someone might pay for me to go back and hang out with the Shipibo shamans for a year or two? I couldn’t have imagined anything better.

I took to the woods that weekend and drew inward to reflect on the business concept and the bizarre idea of actually going for it. My thoughts tended toward: You’ve seen the hardship in the indigenous communities. We don’t live in a perfect world. While it would be amazing to go down and do your research, who is actually going to read a paper on Shipibo ethnolinguistics? What impact will it have? On the other hand, on the off chance this crackpot guayusa idea becomes something, it could make a real difference in the lives of lots of people.

A company like the one we envisioned, I thought, could be a way to weave connections between the indigenous world and the modern world, and I liked that it would work on many levels. First and foremost, it would be a delicious product with real benefits. More deeply, I thought, over time it could be a way for Western people to learn more about indigenous traditions and for indigenous people to find a sustainable way into the world economy. If capitalism and consumerism are the languages of the modern world, I reasoned, why not find a way to address people in their native tongue?

In my grant proposals I had written about how the Shipibo use songs to transmit their ancestral knowledge of the tribe’s history, mythology, and local ecology to new generations. In the same way, the Shipibo and many other indigenous tribes in the Amazonian rainforest also use plants as a foundation of their ethnic identity and teach young people about their proper identification, preparation, and use.

On the other side of the equation, I thought, much of American history and mythology is passed on to young people through brand identity—from the products people buy, the TV shows they watch, the political parties they belong to, and the sports teams they passionately support.

I was intrigued by Yogi Bhajan, who brought Kundalini yoga to the United States and began a foundation devoted to spreading its spiritual practices. In 1969 he also started Yogi Tea. It is perfectly possible to enjoy a cup of Yogi Tea without a thought to the spiritual movement behind it, and I’m sure that’s what the vast majority of people do. However, those with a little more interest can find entry to a spiritual worldview via the tea, and go as deep as they wish (although there is plenty of controversy over Bhajan’s integrity). I saw in our potential tea company a similar way to provide layers of access into the world of indigenous Amazonian traditions.

But as much as those heady thoughts about the possibilities for our potential company absorbed me, I was still fundamentally terrified and extremely aware of the fact that I was about the furthest thing from a businessman one could be.

Realizing I needed to shift gears from the mental knot I’d created from the intense deliberation, I reverted to the simple practice that had gotten me through many grueling experiences in the Amazon: I put my hand on my heart and reflected on everything that I was grateful for.

I felt a deep peace wash over me and was hit by a clear awareness that multiple options didn’t exist: this was what we had to do. I remembered the feeling I’d had four months earlier at the end of my last plant dieta and realized this was what it had launched me toward. I felt that we were on the brink of birthing something new and positive into the world. Looking back, I honestly don’t think that I would have decided to pursue the guayusa idea if I hadn’t taken this time to tap into the invisible undercurrents that were less pronounced and less vocal than my fears. By letting my heart speak for me, I realized that I had no choice. Of course, my youthful ignorance must have influenced my decision making on some level too, since I had no real concept of the many, many obstacles that lay ahead in the coming years.

Dan went through his own reflective process and decided he was also in! As our graduation ceremony approached, we made plans to head to Ecuador. Now all we had to do was figure out how to get indigenous Ecuadorian farmers to grow a plant that had never been commercially produced, learn how to dry and process it, ship it to the U.S., turn it into a product, get it into stores, and compete with Coca-Cola and Red Bull . . .

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (September 1, 2018)

- Length: 272 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501156038

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"A must-read story fueled by adventure, passion and purpose.” —Blake Mycoskie, founder of TOMS Shoes

"Rich with tools and guidance for how entrepreneurs can accomplish ambitious social missions by building thriving businesses, Fully Alive offers important insight for the future of how business will be done." —John Mackey, founder and CEO of Whole Foods Market

“We need new thinking to tackle the massive environmental and structural problems the world faces today. Tyler Gage points a way forward, using ancient knowledge and practices and lays a foundation for its application in modern business.” —Rose Marcario, CEO and President of Patagonia, Inc.

“Fully Alive offers a refreshingly honest, often brutally frank blend of big picture inspiration about how we might achieve truly sustainable commerce that promotes preventative health and fair trade with indigenous cultures along with pragmatic learnings that will help inform any entrepreneur about facing and overcoming challenges, especially with mission-driven businesses.” —Gary Hirshberg, cofounder, chairman, and former CEO of Stonyfield Farm

“Whether you’re an entrepreneur, business person, seeker or lover of adventure stories: Read this book.” —Mark Rampolla, founder of ZICO Coconut Water and author of High Hanging Fruit

“Adventure story, a spiritual quest, and a business manual, Fully Alive teaches how passion can be harnessed to improve lives and make an impact that matters.” —Yolanda Kakabadse, International President of the World Wildlife Fund; former Ecuadorian Minister of Environment

“Engaging, fun, and insightful, Fully Alive vividly illustrates the exhilarating, frustrating, exhausting, and rewarding process that is starting a social venture.” —Russ Siegelman, professor at Stanford University

“Tyler Gage represents a hope-inspiring new generation of social entrepreneurs who are proving that conscious business can be a powerful force for good.” —Paul D. Rice, president and CEO of Fair Trade USA

“A compelling story of purpose, perseverance, patience, and partnership. Runa is an innovative and sustainable social business that is positively impacting the lives of countless indigenous people in the Amazon.” —Ann Veneman, former Executive Director of UNICEF and former US Secretary of Agriculture

“In this powerful and riveting book, Tyler manages to achieve a rare combination of three distinct things: Vividly conveying an extraordinary hero’s journey, while narrating a highly educational text book about business and startups, and expressing a heartfelt, inspiring, no-holds-barred treatise on shamanic practices applied to a modern business. I could not put it down.” —José Luis Stevens, PhD, author of Awaken the Inner Shaman

“Tyler Gage knows how to tell a story, and he has amazing stories to tell. Readers of Fully Alive will enjoy the journey. You’ll discover that powerful answers to profound questions can be found in the most unexpected places.” —Doug Hattaway, founder and CEO of Hattaway Communications and former Advisor to Hillary Clinton and Al Gore

“Tyler’s accomplishment as a young, visionary entrepreneur who has built a sustainable social enterprise has been an inspiration to our students. Fully Alive provides a comprehensive understanding for how to optimize social enterprise creation to generate business success while changing lives and sustaining incomes of vulnerable populations.” —Scott B. Taitel, Director of Social Impact, Innovation, and Investment, NYU Wagner

“Fully Alive is a great story of how curiosity, tenacity, a little naivety, and a lot of personal growth can be the right recipe for launching a social enterprise. I thoroughly enjoyed the ride, from the hills of California, to the halls of Brown University, to the indigenous communities of the Amazon, to the board room in New York.” —Lauren Hattendorf, Head of Investments, Mulago Foundation

“Fully Alive offers many powerful lessons and tools across a range of topics, including leadership, ethics, and strategy—an excellent read for students, entrepreneurs, and anyone looking to embark on new ventures (or adventures!) in their life.” —Alan Harlam, Director of Social Innovation, Brown University

“Runa’s story illustrates that doing well by doing good is not simply a cliché. It was what motivated its founders in the first place, and is the basis of its continued great success.” —Danny Warshay, Professor and Executive Director, Jonathan M. Nelson Center for Entrepreneurship, Brown University

“A refreshingly honest story of young entrepreneurs with a unique mix of social purpose, grit, and creative strategy.” —Tom First, Castanea Partners

“Exciting and inspirational. Tyler Gage paves the way for the future of business! Spiritual/travel adventure meets business manual—Fully Alive is as entertaining as it is a blueprint for the new wave of business practice.” —Anjali Kumar, idea acupuncturist and author of Stalking God

“A delightfully honest and insightful account of a mission-driven business and the diverse, sometimes funny, sometimes tortuous trajectory of that venture. His triumphs and mistakes, accompanied by dogged perseverance, make this not only a worthy read, but valuable to any entrepreneur who is willing to get right up to their neck in something worth doing right.” —Chris Kilham, Medicine Hunter

“A beautiful book about how Amazonian plants can teach us to shapeshift our world—a powerful and illuminating message!” —John Perkins, New York Times bestselling author of Confessions of an Economic Hit Man

“The case study of how Tyler and the Runa team innovate upon indigenous knowledge and translate it to benefit a diversity of stakeholders has great educational value.” —Dr. Florencia Montagnini, professor at Yale University

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Fully Alive Trade Paperback 9781501156038

- Author Photo (jpg): Tyler Gage Caroline Bennett(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit