Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

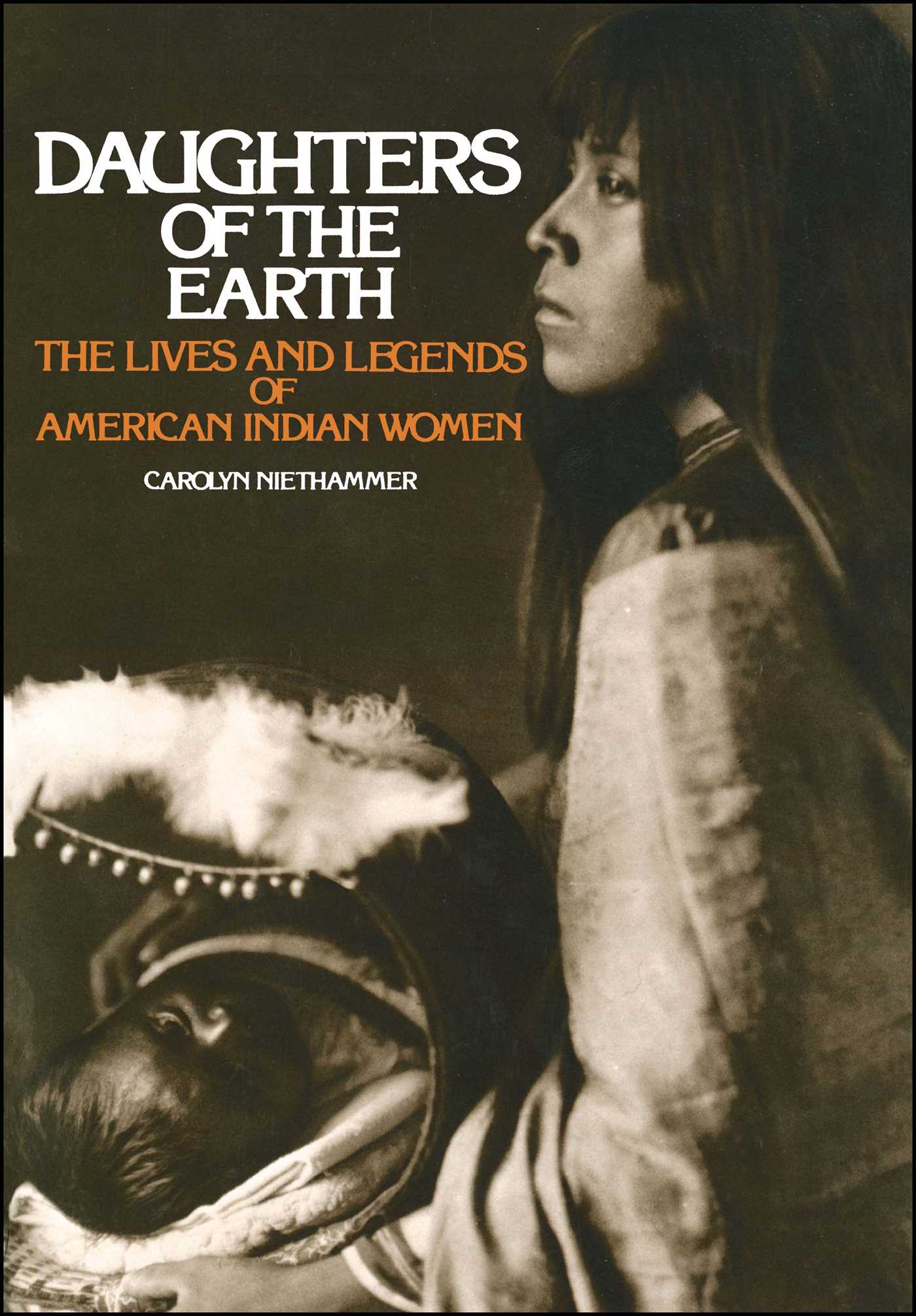

She was both guardian of the hearth and, on occasion, ruler and warrior, leading men into battle, managing the affairs of her people, sporting war paint as well as necklaces and earrings—she is the Native American woman.

She built houses and ground corn, wove blankets and painted pottery, played field hockey and rode racehorses.

Frequently she enjoyed an open and joyous sexuality before marriage; if her marriage didn't work out she could divorce her husband by the mere act of returning to her parents. She mourned her dead by tearing her clothes and covering herself with ashes, and when she herself died was often shrouded in her wedding dress.

She was our native sister, the American Indian woman, and it is of her life and lore that Carolyn Niethammer writes in this rich tapestry of America's past and present.

Here, as it unfolded, is the chronology of the Native American woman's life. Here are the birth rites of Caddo women from the Mississippi-Arkansas border, who bore their children alone by the banks of rivers and then immersed themselves and their babies in river water; here are Apache puberty ceremonies that are still carried on today, when the cost for the celebrations can run anywhere from one to six thousand dollars. Here are songs from the Night Dances of the Sioux, where girls clustered on one side of the lodge and boys congregated on the other; here is the Shawnee legend of the Corn Person and of Our Grandmother, the two female deities who ruled the earth. Far from the submissive, downtrodden “squaw” of popular myth, the Native American woman emerges as a proud, sometimes stoic, always human individual from whom those who came after can learn much.

At a time when many contemporary American women are seeking alternatives to a lifestyle and role they have outgrown, Daughters of the Earth offers us an absorbing—and illuminating—legacy of dignity and purpose.

She built houses and ground corn, wove blankets and painted pottery, played field hockey and rode racehorses.

Frequently she enjoyed an open and joyous sexuality before marriage; if her marriage didn't work out she could divorce her husband by the mere act of returning to her parents. She mourned her dead by tearing her clothes and covering herself with ashes, and when she herself died was often shrouded in her wedding dress.

She was our native sister, the American Indian woman, and it is of her life and lore that Carolyn Niethammer writes in this rich tapestry of America's past and present.

Here, as it unfolded, is the chronology of the Native American woman's life. Here are the birth rites of Caddo women from the Mississippi-Arkansas border, who bore their children alone by the banks of rivers and then immersed themselves and their babies in river water; here are Apache puberty ceremonies that are still carried on today, when the cost for the celebrations can run anywhere from one to six thousand dollars. Here are songs from the Night Dances of the Sioux, where girls clustered on one side of the lodge and boys congregated on the other; here is the Shawnee legend of the Corn Person and of Our Grandmother, the two female deities who ruled the earth. Far from the submissive, downtrodden “squaw” of popular myth, the Native American woman emerges as a proud, sometimes stoic, always human individual from whom those who came after can learn much.

At a time when many contemporary American women are seeking alternatives to a lifestyle and role they have outgrown, Daughters of the Earth offers us an absorbing—and illuminating—legacy of dignity and purpose.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

The Dawn of Life

CHILDBIRTH IN NATIVE AMERICA

When the North American continent was younger and wild animals and dark mysteries still inhabited the woods and the plains and the mountains, women usually gathered unto themselves for the ritual of birth. For unusually difficult labors or when the time was right for certain necessary ceremonies, a medicine man might be called to render his special potions or incant powerful prayers, but, in general, males were infrequent participants in such business. It was the women who performed the practical and ceremonial duties that readied the infant for life and gave it status as an individual. These tasks were performed so often as to be commonplace, yet they were heavy with meaning at each new birth, for such rituals were elemental to the existence of women in early America.

Being a mother and rearing a healthy family were the ultimate achievements for a woman in the North American Indian societies. There was no confusion about the role of a woman and very few other acceptable patterns for feminine existence. Many Indian women attained distinction as craftswomen or medical practitioners, but this in no way affected their role as bearers and raisers of children.

Women's lives flowed into what they saw as the natural order of the universe. Mother Earth was fecund and constantly replenishing herself in the ongoing cycle of birth, growth, maturity, death, and rebirth. The primitive women of our continent considered themselves an integral part of these ever-recurrent patterns and accepted a role in which they were an extension of the spirit mother and the key to the continuation of their race. Not separate from, but part of, these deeply religious feelings was the practical consideration that many children were needed to help with the work and to take care of the parents as they grew older. In those simpler days, children were a couple's savings account and insurance.

SEX AND PREGNANCY

Women in most Native American cultures knew pretty clearly how they got pregnant, although even here beliefs varied when it came to the details.

The Gros Ventres of Montana and the Chiricahua Apaches of southern Arizona were among those groups believing that pregnancy could not occur as the result of a single sex act. One Apache explained that if a couple had intercourse three times a week they could have a baby started in about two or three months. But the informant also said, "I know a girl who had intercourse with a man many times in one night. If a girl did it at that rate, it wouldn't take any time at all to get a child started." As another Apache related, "When a man has intercourse with a woman some of his blood (semen) enters her. But just a little goes in the first time and not as much as the woman has in there. The child does not begin to develop yet because the woman's blood struggles against it. The woman's blood is against having the child; the man's blood is for it. When enough collects, the man's blood forces the baby to come."

Although many sexual encounters were believed necessary to create a child, as soon as an Apache woman noticed the first signs of pregnancy, she ceased her sexual activity to prevent injury to the baby growing within her.

The Hopi of northern Arizona, on the other hand, were convinced that continued sex was good for both the prospective mother and the baby; a woman slept with her husband all through her pregnancy so that their continued intercourse could make the child grow. It was likened by one Hopi to irrigating a crop -- if a man started to make a baby and then stopped, his wife would have a hard time.

The Kaska Indians of northwestern Canada also maintained that repeated sex during early pregnancy developed the embryo, but warned that too much indulgence would produce twins. As soon as a Kaska woman felt the stirrings of life in her womb, she was warned to discontinue her sexual life. Mothers advised their pregnant daughters to use their own blankets and to sleep facing away from their husbands to avoid temptation.

Among most of the tribes, however, pregnant women continued a moderate sex life until the later stages of their pregnancy, much as many women do today. There were a few groups where custom completely forbade intercourse during pregnancy. In the area which is now Wisconsin, Fox women abstained from sex throughout pregnancy for fear their babies would be born "filthy," and down near where the Colorado River emptied into the Gulf of California, pregnant Cocopah women slept alone lest their babies be born feet first.

A BOY -- OR A GIRL?

Most Indian mothers welcomed each baby regardless of sex and wished primarily that the child be strong and healthy. But it is universal for a woman carrying a child for nine long months to wonder whether her labor will produce a son or a daughter. Out on the Great Plains when an Omaha woman wanted to ascertain the sex of her coming child she took a bow and a burden strap to the tent of a friend who had a child who was still too young to talk. She offered the two articles to the baby. If the little child chose the bow, the unborn would be a boy; if the child paid more attention to the burden strap, the coming baby would be a daughter.

There were some societies, particularly those in the far north where life was hard, that did not welcome an abundance of daughters. But it is said that the Huron, who lived north of Lake Ontario, rejoiced more at the birth of a girl child, for girls grew into women who had more babies, and the Huron wanted many descendants to care for them in their old age and protect them from their enemies.

In the matrilineal societies of the Hopi in the Southwest, where the status of women was high, a woman wished to give birth to many girl babies, for it was through her daughters that a Hopi woman's home and clan were perpetuated. A boy was not unwelcome, for he also belonged to his mother's clan, but when he married, his children would belong to the house and clan of their own mother.

Generally the sex of the baby was left to fate, but among the Zuni, neighbors of the Hopi on the beautiful but arid and windswept deserts of the Southwest, if a couple desired a girl child they went to visit the Mother Rock near their pueblo. The base of the rock was covered with symbols of the vulva and was perforated with small excavations. The pregnant woman scraped a tiny bit of the rock into a vase and placed it in one of the cavities. Then she prayed that a daughter would be born who would be good, beautiful, and virtuous, and who would display skill in the arts of weaving and pottery-making. If by chance a boy child was born, the Mother Rock was not blamed. Instead it was believed that the heart of one of the parents was "not good."

PRENATAL HEALTH CARE

In those early days, infant mortality was alarmingly high and many women died in childbirth. Prospective mothers used every means at their disposal to ensure safe delivery and healthy children, but because medicinal procedures were so primitive, these women relied on measures which today we label "superstition" and "sympathetic magic," including a vast and varied range of taboos. Pregnant Indian women were almost universally warned against looking at or mocking a deformed, injured, or blind person for fear their babies would evidence the same defect; being in the presence of dying persons and animals was likewise unhealthy for both the mother and baby. Among the Flathead Indians of Montana neither the mother nor father could go out of the lodge backward or a breech birth would follow, nor were either of the prospective parents allowed to gaze out of a window or door. If they wanted to see what was going on outside, they were to go all the way outdoors and look around, lest the baby be stillborn.

There were also taboos on certain foods. Some typical dietary restrictions for pregnant Indian women prohibited eating the feet of an animal, to avoid having the baby born feet first; the tail of an animal, to prevent the child's getting stuck on the way out; berries, so that the baby would not carry a birthmark; and liver, which would darken the child's skin.

The Lummi Indians of what is now northwest Washington were a fairly wealthy group whose home on the productive coastlands offered them a vast variety of foods. This bounty enabled them to place taboos on many foods, including halibut, which was believed to cause white blotches on the baby's skin; steelhead salmon, which caused weak ankles; trout, which produced harelip; and seagull or crane, which would produce a crybaby. The prospective mother also had to abstain from shad or blue cod, which would induce convulsions in the child; venison, which would lead to absentmindedness; and beaver, which might cause an abnormally large head.

Among some of the groups with less abundant food resources, restrictions were limited to only certain parts of animals. Pregnant women were warned that eating tongue would cause the baby's tongue to loll, while the ingestion of an animal's tail might create problems during labor.

Though there were many foods that could not be eaten, there is some evidence that Indian women years ago, like many present-day women, did have cravings for special foods during pregnancy. The Reverend John Heckewelder, writing in the late 1700s, reported that he had witnessed what he called "a remarkable instance of the disposition of Indians to indulge their wives." Apparently, famine had struck the Iroquois in the winter of 1762, but a pregnant woman of that tribe longed for some Indian corn. Her husband, having learned that a trader at Lower Sandusky had a little of the desired commodity, set off on horseback for the one-hundred-mile trek. He brought back as much corn as filled the crown of his hat, but he returned walking and carrying his saddle, for he had had to trade his horse for the corn. Heckewelder continued, "Squirrels, ducks and other like delicacies, when most difficult to be obtained, are what women in the first stages of their pregnancy generally long for. The husband in every case will go out and spare no pains nor trouble until he has procured what is wanted. The more a man does for his wife, the more he is esteemed, particularly by the women."

Each tribe had certain herbs and teas that were believed to relieve aches and pains and promote the health of prospective mothers. A Crow medicine woman named Muskrat used two roots which had been revealed to her by a supernatural who appeared to her twice while she was asleep. During the first vision she was instructed to chew a certain weed if she wished to give birth without suffering. Later she was taught about another plant and was told it was even better than the first. Another Crow woman paid a horse to a visionary who taught her a formula made from a combination of certain roots and powdered, dry horned toad. The resulting powder was used in giving backrubs.

Bear's Medicine for Pregnant Women

(HUPA)

While walking in the middle of the world Bear got this way. Young grew in her body. Ail day and all night she fed. After a while she got so big she could not walk. Then she began to consider why she was in that condition. "I wonder if they will be the way I am in the Indian world?" She heard a voice talking behind her. It said, "Put me in your mouth. You are in this condition for the sake of the Indians." When she looked around she saw a single plant of redwood sorrel standing there. She put it into her mouth. The next day she found she was able to walk. She thought, "It will be this way in the Indian world with this medicine. This will be my medicine. At best not many will know about me. I will leave it in the Indian world. They will talk to me with it."

But besides consuming herbal medicines, avoiding certain foods, and watching their own behavior, some Indian women had to be careful not to become victims of witchcraft during pregnancy. Matilda Cox Stevenson, who lived with and studied the Zuni Indians in the area of northwest New Mexico for many years in the late 1800s, wrote that she had helped a pregnant Zuni woman who was suffering from a cough and from pain in the abdomen. Although the woman felt better after taking the simple home remedies Mrs. Stevenson gave her, her family still thought it wise to call in the native surgeon. When he arrived and began to treat the pregnant woman, he appeared to draw from her abdomen two objects which he claimed were mother and child worms. Mrs. Stevenson wrote that one was about the length of her longest finger, while the other was smaller. The doctor pronounced this evidence that the woman had been bewitched and assured the family that it was well he had been sent for promptly, for in time these worms would have eaten the child and caused its death. Later, when trying to figure out who could have bewitched her, the Zuni woman recalled that some weeks before she had been grinding corn while kneeling next to the sister of a witch, and this woman had touched her on the abdomen. She decided it was probably then that the worms had been cast in.

CHILDBIRTH CUSTOMS

Because in some groups the older women were unwilling to talk about the actual birth process, many young Indian women were remarkably unprepared for the birth of their first child. Pretty-shield, a Crow woman whose story is told in the book Red Mother, related how she was playing with some girl friends during her first pregnancy and felt a quick little pain. When she sat down laughing about it, one of her friends guessed what the pain meant and warned Pretty-shield's mother, who immediately consulted a medicine woman named Left-hand. The mother and Left-hand had to coax Prettyshield to come with them to the special skin lodge they had pitched for the occasion. Outside the lodge Pretty-shield noticed that one of her father's best horses was tied up with several costly robes on his back -- an advance payment to old Left-hand for her assistance. Pretty-shield described the medicine woman as having her face painted with mud, her hair tied in a big clump on her forehead and carrying in her hand some of the grass-that-the-buffalo-do-not-eat.

Inside the tipi a fire was burning and a mat made of a soft buffalo robe was folded with the hair side out to serve as a bed. As was customary, two stakes had been driven into the ground, and other buffalo robes had been rolled up and piled against them so that when Pretty-shield knelt on the mat and took hold of the stakes her elbows rested on the pile of robes.

First Left-hand took four live coals from the fire, spacing them evenly on the ground between the door of the tipi and the bed. Then she instructed her patient to step over the coals and go to the bed. Left-hand, wearing a buffalo robe and grunting like a buffalo cow, followed behind Pretty-shield, instructing her to "walk as though you are busy" and brushing the girl's back with the tail of the robe.

Pretty-shield concludes, "I had stepped over the second coal when I saw that I should have to run if I reached my bed-robe in time. I jumped the third coal, and the fourth, knelt down on the robe, took hold of the two stakes, and my first child, Pine-fire, was there with us."

Anthropologist Ruth Underhill tells a somewhat similar tale in The Autobiography of a Papago Woman. Chona, a Papago woman of southern Arizona, described the birth of her first child, which occurred when she herself was but a teenager. She didn't know quite when to expect her baby, but when she felt a pain one day while stooping over to pass through the low door to her grass house, she surmised that the time had come for the baby's arrival. As was true for women among many North American Indian cultures, Papago mothers were required by custom to have their babies in a special segregation hut apart from the main dwelling. Chona knew that it was time to go to the "Little House" and did not wish to have such a dreadful thing happen to her as to be caught inside the regular house in childbirth. She announced her destination to her husband's aunt -- her first mention of labor pains -- and left to cross the wash between the main house and the Little House.

"When I reached the near edge of that gully I thought I had better run," Chona related. "I ran fast; I wanted to do the right thing. But I dropped my first baby in the middle of the gully. My aunt came and snipped the baby's navel string with her long fingernail. Then we went on to the Little House." Later one of her sisters-in-law asked her why she hadn't said anything about her pains. The other women hadn't known she was suffering because they had heard her laughing. Chona's response was, "Well, it wasn't my mouth that hurt. It was my middle."

Chona and her baby had to stay in the segregation hut for a full month, during which time she was not allowed to bathe, for fear she would get rheumatism. Her family brought her food which she cooked with no salt. "When the moon had come back to the same place," it was time for the purification ceremony. Chona, her husband, and the baby went to a medicine man, or shaman, who was a specialist in child-naming. The shaman prepared a mixture of clay, water, and pounded owl feathers which both parents and the child were required to sip; then the shaman gave the child a name. If Papago parents neglected to have this ceremony performed, they risked the health of both themselves and the new baby.

Not all Indian women had births as easy as those of Pretty-shield and Chona, but they were nevertheless expected to endure the pain without crying out. Huron women who fussed while they were in labor were chided for being cowardly and failing to set a good example for others. A Huron woman proved her courage by her brave conduct during childbirth just as a man proved his courage in battle. The Gros Ventres of Montana believed that a woman who cried out drove the child back, and a mother who turned and twisted in pain might tangle the cord around the child.

During her labor an Indian woman was usually assisted by her female relatives or other women of her tribe who had special knowledge of birth customs. They supported the woman as she knelt or squatted, rubbed her back, pressed down on her abdomen to force the child out, encouraged the mother, and cared for her and the child immediately after the birth. A good example of how the women helped each other can be found among the Kwakiutl of British Columbia. In good weather a woman might deliver outside, but in bad weather she remained in the longhouse. Usually two professional midwives came to assist. They first dug a pit and lined it with soft cedar bark. Then one of them sat down on the edge of the shallow excavation, stretching her legs across it so that her feet and calves rested on the opposite edge. The pregnant woman sat on the midwife's lap, straddling the helper's legs so that both her own legs hung down inside the pit. The two women clasped each other's arms tightly, while the second midwife squatted behind the woman who was delivering, pressing her knees against her back, wrapping her arms around the mother's shoulders, and blowing down her neck in order to produce a quick and easy delivery. The baby dropped into the pit and remained there until the afterbirth was delivered. Then the mother went to bed for four days.

Some of the midwives were quite skilled at their profession, often being able to turn a baby in the womb to ensure a safer and easier delivery. They were also good psychologists, knowing just how to talk to, calm, and comfort a woman who was suffering a great deal. But sometimes, in very difficult cases, the power and skill of the midwives were not enough, and doctors with more power had to be called in. A Gros Ventre woman told of how she had been helped by such a doctor during one of her pregnancies. The man was old and blind and when called to help, he sat next to the suffering woman with a pot of medicine beside him. When the woman cried out in pain he touched her with the end of a stick and the cramps went away. When the woman complained that she was tired, the midwife assured her that it would soon be over, but the doctor disagreed. The labor continued for several more hours until the doctor predicted the baby would be born shortly, and he was right. It was believed that the medicine man's power allowed him to know what was happening without seeing or touching the laboring woman.

Although women generally gathered together for the birth of babies, in some North American tribes the expectant mother had to face the birth process alone. Women in the Caddo group near the border of what are now Mississippi and Arkansas were instructed, when the time of their delivery neared, to go to the bank of the nearest river and to build a little shelter, with a strong forked stick positioned in the center. Supporting themselves with this stick they gave birth all alone and then immediately waded into the stream, even if they had to break ice to do so, washed themselves and the baby, and returned home to continue their normal lives.

A report survives from 1790 of four Tukabahchee women (a tribe of the Greek confederacy located in Alabama) who came to sell horse ropes to some white men on a cold and rainy night in December. Because of the bad weather, the women stayed overnight, and about midnight, one of the women went into labor. Her mother instructed her to take fire and go to the edge of a swamp about 160 yards away. She went alone, delivered her own baby, and the next morning took the infant on her back and returned home with the other women through the still-falling rain and snow.

Many of the native North American cultures insisted that, following birth, both mother and newborn child remain in seclusion, particularly away from all men, for a period of time ranging from a few days to as long as three months. The Nez Percé women in northern Idaho entered a special underground lodge two or three months before the baby was expected and remained for two weeks after the birth. For the most part, women in seclusion were well cared for. Life for them was hard, and rather than being chagrined at being excluded from the rest of the group, they no doubt welcomed a time of recuperation before returning to their strenuous daily duties.

CEREMONIES OF CHILDBIRTH

In some of the Indian societies, a great deal of ritual accompanied each birth. The Hopi infant began life in a society where elaborate religious ceremonials dominated much of village life. Each new baby was immediately immersed in the rich, sacred traditions that would so fully shape its life experience. In the Hopi pueblos a young mother was often alone at the moment of birth, but as soon as the baby had slipped out of the birth canal onto the patch of warm sand, the newborn's maternal grandmother entered the room to sever and tie the cord and to make her daughter and new grandchild comfortable. After washing the baby she rubbed its body with ashes from the corner fireplace so that its skin would always be smooth and free of hair. Then she took the afterbirth and deposited it on a special placenta pile at the edge of the village.

Very soon the baby's paternal grandmother arrived and began to take up her duties as mistress of ceremonies for all the rituals that would be performed during the twenty-day lying-in period and for the culminating dedication of the baby to the sun. Her first task was to secure a heavy blanket over the door so that no sunlight could enter the room where the mother and baby lay. It was thought that light was harmful to newborn children, and so the baby began its life on earth in a room almost as dark as the womb from which it had just emerged.

For eighteen days the mother and baby lay at rest in the darkened room. Each day a mark was made on the wall above the baby's bed and a perfect ear of corn laid under each mark. On the nineteenth day the mother got up and spent the day grinding corn into sacred meal to be used in the special ceremony the next day.

On the next morning the new mother's female relatives arrived at her home well before dawn, dressed in their most colorful shawls and carrying gifts of cornmeal and perfect ears of corn. When all the guests had arrived the solemn ceremony for the dedication of a new life was begun. First the mother was ritually purified. Her hair and body were washed in suds made from the root of the yucca plant, and then she took a steambath by standing over a bowl of hot water. Next all the grandmothers and the aunts each took a turn at bathing the baby in yucca suds and giving it a name.

While all this was taking place inside the home, the father, who since the birth had been living in his religious society's kiva, or underground ceremonial chamber, was stationed on the flat roof of the stone house watching for the sun. When the sacred Sun Father began to appear, the father alerted the women, who hastily took the child to the edge of the mesa. The grandmother who carried the baby crouched low so that no light would fall on the infant. Then, as the sun appeared over the horizon, the grandmother lifted the baby, turning her tiny bundle so the rays fell directly on the little face. Taking a handful of prayer meal she sprinkled some over the baby while reciting a short prayer. She flung the rest of the meal over the edge of the mesa toward the sun. The baby, now a full member of the family, was taken home and allowed to nap while the rest of the family enjoyed a breakfast feast.

Zunis recognized the sex of a baby in a special ceremony performed soon after birth: the newborn female child had a gourd placed over her vulva so that her sexual parts would be large, and the penis of a baby boy was sprinkled with water so that his organs would be small. Of course this ceremony was performed by the women attending the new mother so it reflected the feminine ideal for the physical proportion of the sexual organs.

Because of the extremely high infant mortality rate among the early Native Americans, ceremonials were often delayed until the child was about a year old.

Among the Omaha a newborn child was not considered a member of the tribe or kin group but just another living being whose arrival into the universe should be announced so that it would have an accepted place in the life force that united all nature, both animate and inanimate. On the eighth day of the baby's life a small ritual was held, and a prayer was recited to the powers of the heavens, the air, and the earth for the safety of the child, who was pictured as about to travel the rugged road of life stretching over four hills, marking the stages of infancy, youth, adulthood, and old age.

When the baby had grown and was able to walk, another ritual was held, during which the child was finally recognized as a real human being and a member of the tribe. The baby was given a new name and a new pair of moccasins. These moccasins always had a little hole in them so if the Great Spirit called, the baby could say, "I can't travel now, my moccasins are worn out."

Prayer for Infants

(OMAHA)

Ho! Ye Sun, Moon, Stars, all ye that move in the heavens,

I bid you hear me!

Into your midst has come a new life.

Consent ye, I implore!

Make its path smooth, that it may reach the brow of the first hill!

Ho! Ye Winds, Clouds, Rain, Mist, all ye that move in the air,

I bid you hear me!

Into your midst has come a new life.

Consent ye, I implore!

Make its path smooth, that it may reach the brow of the second hill!

Ho! Ye Hills, Valleys, Rivers, Lakes, Trees, Grasses, all ye of the earth,

I bid you hear me!

Into your midst has come a new life.

Consent ye, I implore!

Make its path smooth, that it may reach the brow of the third hill.

Ho! Ye birds, great and small that dwell in the forest,

Ho! Ye insects that creep among the grasses and burrow in the ground,

Into your midst has come a new life.

Consent ye, I implore!

Make its path smooth that it may reach the brow of the fourth hill!

Ho! All ye of the heavens, alt ye of the air, all ye of the earth:

I bid all of you to hear me!

Into your midst has come a new life.

Consent ye, consent ye all, I implores!

Make its path smooth -- then shall it travel beyond the four hills.

The Omahas in eastern Nebraska believed that certain people had the gift of understanding the various sounds made by a baby, so when a little one cried persistently and could not be comforted, one of these persons was summoned. Sometimes the person decided that the child was crying because it did not like its name; in such case, the name would be changed.

NATURAL CHILDCARE

For a modern mother the thought of raising an infant without access to a drugstore full of powders, lotions, and disposable diapers would be appalling, but for centuries North American Indian mothers managed to raise babies with only materials supplied by Mother Earth and reliance on certain magical rites.

Because all Indian mothers breast-fed their babies, it was necessary that their breasts and nipples be in good condition. On the Washington coast Lower Chinook women spent the time of their confinement rubbing their breasts with bear grease and heating them with hot rocks or steam, while in northeastern Washington, Salish mothers heaped their sore breasts with heated pine needles. There seems to have been a feeling among many Indian groups that the colostrum, the yellowish fluid that precedes the appearance of the milk, was not good for the baby, and in some cases the babies were not fed until the milk appeared. Cultures that imposed such restrictions on new mothers had to come up with some way to relieve the painful pressure that resulted. Yurok women on the coast of northern California made the period bearable by softening their breasts over the steam of water mixed with herbs, which caused the colostrum to flow out. Gros Ventre mothers usually had someone else draw out the "first milk" and spit it out, whereas if a woman was alone when the child was born she often had a puppy suck out the colostrum. A Gros Ventre woman said that when her own daughter delivered her firstborn, an old woman offered to draw off this "first milk," but the daughter refused; as a consequence, the daughter could give milk only from one breast.

In the story of her life, Delfina Cuero, a Diegueno Indian from the southern California coast, explained the natural means she used to care for a baby's navel.

So that the navel will heal quickly and come off in three days, I took two rounds of cord and tied it (the navel) and then put a clean rag on it. I burned a hot fire outside our hut to get hot dirt to wrap in a cloth. I put this on the navel and changed it all night and day to keep it warm until the navel healed. To keep the navel from getting infected I burned cow hide or any kind of skin till crisp, then ground it. I put this powder on the navel. I did this and no infection started in my babies. Some women didn't know this and if infection started I would help them to stop it this way.

Mothers powdered and oiled their babies with what was at hand. The Mandan, living on the northern Great Plains, pounded buffalo chips into a powder, warmed the powder with hot stones, and rubbed it on the baby's bottom, under its arms, between its legs, under its toes, and between its fingers. Mandan babies were also greased and painted with red ocher as a prevention against chafing. Down in the South, along the Mississippi River, Natchez babies were rubbed with bear grease to keep their sinews flexible and to prevent fly bites.

Women of early North America had their own forms of disposable diapers. Among the Natchez', Spanish moss was tied to a baby's thighs and buttocks before the infant was tied in its cradleboard. Up in what is now Saskatchewan and Manitoba, Cree babies were kept in a bag stuffed with dried moss, rotted and crumbled wood, or pulverized buffalo chips mixed with cattail down. When a child soiled the bag, the moss was shaken out, and a fresh supply of absorbant was stuffed in. Hopi babies were diapered with fine cedar bark which had been softened until it was absorbent and spongelike. When the diaper became wet it was rubbed in clean sand and put in the sun to dry. After the hot Arizona sun had dried and deodorized the diaper it was shaken clean, resoftened, and used again.

Reportedly, Huron mothers, living in southeastern Ontario, were a bit more creative. They swaddled their babies in furs on a cradleboard, wrapping them in such a way that the urine was carried off without soiling the baby; a boy was wrapped so that just the tip of his penis protruded, and for girls a corn leaf was cleverly positioned for the same purpose.

The cradleboard, practically a universal symbol of American Indian babyhood, was the forerunner of today's widely used molded plastic baby carrier. Cradleboard styles varied widely from tribe to tribe, but all provided a firm, protective frame on which babies felt snug and secure. A baby in a cradleboard could be propped up or even hung in a tree so it could see what was going on and feel a part of family activities. The Fox Indians thought it necessary to keep a baby in a cradleboard to prevent a long head, a humpback, or bowlegs.

After spending so much time in their cradleboards, Indian children became very attached to them. One Apache mother related that whenever her toddler son was tired or upset he would go and get his cradleboard and walk around with it on his back.

Lullaby for a Girl

(ZUNI)

Little maid child!

Little sweet one!

Little girl!

Though a baby,

Soon a-playing

With a baby

Will be going.

Little maid child!

Little woman so delightful!

INFANT DEATH

Sometimes all the special care and magic ceremonies were not enough to enable the vulnerable infant to survive. Even though Indian mothers could expect to lose at least half of their children in infancy or childhood, each death was a cause for sorrow. Most societies did not provide for dead children the full-scale mourning ceremonies presented for adults, but this did not temper the grief of the mothers, no matter how silently they had to bear their pain. In northern California, a Yokaia mother who had lost her baby went every day for a year to a place where her little one had played when alive or to the spot where the baby's body was cremated. At the cremation grounds she milked her breast into the air, all the while moaning and weeping and piteously calling on her dead child to return.

Young Hopi women often lost their first baby, since they all spent the first year of married life kneeling in front of the grinding stone producing many pounds of cornmeal as payment for their wedding robes. Babies who were born dead or who did not live past infancy were buried in crevices below the pueblos in the rocky slopes of the steep mesas. It was believed that soon after burial the little soul came out of the rocks and hovered near the mother until another baby was born. It could then enter the newborn's body and live again. The little knocks and cracks often heard around the house were thought to be evidence that the soul was near. If a woman's last baby died, the Hopis thought its soul stayed near her until she herself "went away" and took it with her on the trail to the sun.

THE PROBLEM OF INFERTILITY

There were some Indian women who were faced not with the problem of keeping their infants alive but of getting pregnant in the first place. When a Salish woman, in what is now eastern Washington and northern Idaho, did not become pregnant in a reasonable time after she was married, she would go to one of the old women of the tribe who were wise in such lore and would eat the herbs the medicine woman prescribed. If she remained barren her husband wouldn't divorce her, but he would probably take another wife if he could afford it.

The Mandan of North Dakota believed there was a Baby Hill which had an interior just like the earth lodges in which they lived, and many people claimed to have seen the tracks of tiny baby feet on the tops and sides of these hills. An old man supposedly lived in the hill and cared for all the babies that were there. A woman who had been married for a number of years and was still childless would go to one of the hills to pray for a baby, taking along girl's clothing and a ball if she wanted a daughter or a small bow and arrow if she desired a son.

The method used by Paiute women, living near the northeastern corner of California, was a little more risky. If a woman had a regular sex life and still didn't become pregnant, she sometimes resorted to drinking red ants in water. Views on just how effective this treatment was varied from reports of women getting pregnant this way to more skeptical accounts of the treatment which stated that the ants bit the woman all the way down to her stomach and usually killed her. A less dangerous method used by the Paiute women was to hunt for little gray birds that lived in the rocks of that area. If the birds were taken alive and worn near a woman's waist under her dress, they supposedly improved her chances of conceiving. And in what is now southwestern Arizona, a Yuma woman who was having difficulty conceiving might seek the help of a good doctor. Yuma folklore tells the story of one couple who went to such a doctor, who laid them both on the ground in an open space and lifted one after the other under the arms. Deciding that it was the woman who was lacking "seed," the doctor plunged his right arm into the ground as though it were a sharp stick and brought out some very coarse sand which he rubbed all over the woman, in addition to blowing smoke on her belly. Not long after this treatment the woman found herself pregnant.

Among the Havasupai, who live in the bottom of the Grand Canyon, it was so important for a woman to bear children that any barren woman could expect to be divorced. To avoid being cast off, a childless Havasupai woman would resort to rather extreme measures to conceive. One of the more radical cure's for childlessness was drinking the water in which one had boiled a rat's nest, well-saturated with urine and feces.

On the other hand, the Ojibwa, of western Ontario, took a more enlightened attitude toward barren women. Like other early North American groups they considered a woman's chief function to be bearing children; sterility was a deviation from normal and always the fault of the female partner. Yet the sterility of a specific woman, while unfortunate, did not necessarily brand her in her husband's eyes. Ruth Landes, author of The Ojibwa Woman, cites many cases of women who had very happy marriages though they were infertile. Among the women whom Landes points out was Thunder Cloud, who did not have any children with her first husband during their ten years together, nor with her second husband during their eight-year union. Both men cared for her deeply despite her barrenness, and her third husband, with whom she finally conceived, did not seem concerned over her apparent sterility at the time of their marriage. Gaybay, another Ojibwa woman, was married five times and had only one child, vet she was never considered undesirable because of her infertility.

BIRTH CONTROL

Although a large family was the goal of most Indian women, there were many situations in which women desired not to conceive. Perhaps a woman already had more children than she could feed and care for, perhaps she wanted to space her children so she could give more time to each baby as it came along, or maybe she had watched so many of her babies die that she wasn't able to undergo any more grief. And although it might be extremely rare, it was not unheard of for a woman to wish to remain childless, preferring to devote her life to other interests.

Primitive methods of birth control were largely magical and probably not too reliable. The manner in which the placenta was disposed of was widely believed to affect a woman's future childbearing. The Paiute believed that barrenness would result if the placenta was buried upside down or eaten by an animal, while an older Kaska woman, after helping her daughter with a difficult delivery, might fill the expelled placenta with porcupine quills and cache it in a tree out of compassion, to save her daughter the trauma of further childbearing.

Up in northwest Washington, a Lummi Indian mother who desired no more babies hung the afterbirth in a split tree in the hope that as the tree grew together her womb would also close up. Or she might hurl the afterbirth into an eddy in the river or ocean, so that her womb, like the placenta swirling in the water, would twist into a position to prevent conception.

A prevalent idea was that, in addition to preventing births entirely, the proper disposal of a placenta could also help to space the arrival of future babies. Oil the coast of British Columbia any Salish woman who wanted a few years' rest from childbearing directed that the placenta be buried with a scallop shell. Among the Cherokee in the Southeast, the father disposed of the placenta by crossing over two, three, or four ridges in the hills and burying it deep in the ground. He and his wife then felt confident that the number of years that would elapse before the birth of their next child would correspond to the number of ridges he had crossed.

Certain ceremonies were considered helpful in preventing conception. Often the rituals were known only to the old medicine women of a tribe who would secretly perform the rites for the desperate Women who visited them under cover of darkness. Apache maidens who did not wish to have children could quietly seek out, at the time of their first menstruation, a woman to perform a rare and much condemned ritual that would prevent pregnancy. It was said that sometimes an Apache mother who knew the pain and suffering of labor had this ceremony performed for her daughter without the younger woman's knowledge or consent. A special variety of small prickly pear cactus fruit was said to be used in these ceremonies.

There were a number of preparations that Indian women took to avoid pregnancy. Quinault women brewed an abortive from a special thistle plant, while once a week southeastern Salish women made and drank a contraceptive of dogbane roots (Apocynum androsaemifolium L.) and water. If the dogbane didn't work, they could resort to an abortifacient tea made from the leaves and stems of yarrow (Achillea millefolium L.). Havasupais killed and dried a ground squirrel and pulverized it. During menstruation, a woman took some of the powdered meat in her hand, went to a place where she could be alone, and licked the powder from her hand bit by bit while praying that she would not conceive. Yuma Indian women relied partially on drinking a mixture made of mesquite wood ashes and water, but they also believed they could forestall pregnancy by regularly urinating on an ant pile or by strongly and persistently refusing to desire a child.

Among the Gros Ventre of Montana, persons who knew about contraceptives either received their knowledge directly from a supernatural or else had it handed down to them from within their family. Anyone who knew which roots or plants could be used to prevent pregnancy could command a large payment for this knowledge, often as much as two or three horses. A Gros Ventre woman named Coming Daylight confessed to Regina Flannery that she had been offered the power in a dream but when the supernatural had begun to show her how to make a medicine from a moss that grew on logs she had refused the knowledge. The Gros Ventre acknowledged that their contraceptive medicines had certain limitations, and the woman who took them had to follow certain rules, such as not letting anyone who was a parent wear her robe, never sitting on the bare ground, never holding an infant, not sitting on anyone else's bedding, and not having sexual relations with anyone other than her husband. The breaking of any of the rules made the medicine ineffective.

Obviously, many of these contraceptive measures failed and when this happened there wasn't much a woman could do except try another herbal remedy or beat herself on the belly with stones -- and even that didn't always work.

The leeway an Indian woman had in limiting the size of her family depended to a large extent on the society in which she lived. Generally, the groups living in the extreme north of our continent and in what is now the southeastern United States seem to have been the most broad-minded concerning the various methods of "family planning." Other groups were extremely conservative in their customs relating to birth control. The Cheyenne, who lived in the area of Wyoming and South Dakota, considered abortion out-and-out homicide, and a woman who killed her unborn child could expect to be prosecuted as a murderess. On the other hand, though the Papagos of southern Arizona severely criticized a woman who didn't want children, they had no officially sanctioned punishment for women who sought abortions. The only penalties were disapproval and criticism, and although sometimes the censure was so stringent that the woman was left friendless, no one would tell a pregnant Papago woman that she could not seek an abortion. Papagos felt that no one could rightfully interfere with what was really the business of the woman and her family.

INFANTICIDE

Infanticide was not unknown among the Native Americans, and there were many reasons why women had to resort to such an extreme measure of population control. Among the Eskimos living on the extreme northern fringes of our continent, each new child represented an enormous burden for the mother, especially during the summer when a mother was expected to carry the baby over and above her full share of household effects. It was nearly impossible to care for a newborn unless the previous child was able to walk long distances unaided. So if a second child arrived too soon or if a baby was born in a time of scarcity, it was exposed to die of the cold, its mouth stuffed with moss so its plaintive cries would not be heard.

The Kaska, who had a hard life in the subarctic forests of northwestern Canada, sometimes had difficulty finding someone in their group willing to raise a troy orphan. The unwanted baby was placed in a little spruce-bark canoe that was launched on a large river. Tradition says that a child once survived such a voyage and was reared by a beaver from whose teats it nursed.

In the Creek nation all children belonged to the mother, who held the power of life and death over them during the first month of life. It was not uncommon for a woman who had become pregnant by a man who later jilted her to leave her baby to perish in the swamp where it was born. This was also a last resort for mothers whose families had grown larger than they could possibly support. But the baby had to be killed before it was a month old, for if the act was committed later, the mother would be punished with death.

Southeast Salish women occasionally went off alone into the woods to bear their children. A woman who did not wish to keep her baby might choose this option, for the privacy afforded her a chance to return to camp without the infant and to claim that her baby had been born dead. If it was discovered that the mother had killed the baby, the chief ordered her to be severely whipped, but apparently even so painful a punishment was not always enough to discourage this method of controlling family size.

Babies who were born deformed or diseased presented a special problem to Native American tribes, which in general could not afford to support a child that would never be a contributing member of the society. The Eyak, a people of the extreme north, kept their population free of unfit persons by openly burning deformed babies immediately after birth. This rule was rigidly enforced, and any mother attempting to save such a child was herself threatened with death.

The fate of an imperfect Comanche child was decided by the medicine women and the other women attending the birth. Comanches lived on the southern Plains, and if a baby was judged unfit to live, it was carried out on the prairie and left to die. Some families looked upon twins as a disgrace, and occasionally a mother who had two babies at once might dispose of one. An early white traveler named Dr. George Holley discovered and saved one such infant who had been buried in the sand by its mother.

The Hopi, generally a gentle and compassionate people, did not actually kill imperfect babies, but neither did the medicine men struggle to keep them alive, since they felt it would be cruel to subject a child to the taunts, neglect, and hardships that a physical defect would engender. These pueblo people had to work hard to eke out a living in their sandy, rocky, arid country, and unless they were old people who had spent their younger years working and who were currently paying their way by dispensing their wisdom, those who could not work could not eat.

Copyright © 1977 by Carolyn Niethammer

The Dawn of Life

CHILDBIRTH IN NATIVE AMERICA

When the North American continent was younger and wild animals and dark mysteries still inhabited the woods and the plains and the mountains, women usually gathered unto themselves for the ritual of birth. For unusually difficult labors or when the time was right for certain necessary ceremonies, a medicine man might be called to render his special potions or incant powerful prayers, but, in general, males were infrequent participants in such business. It was the women who performed the practical and ceremonial duties that readied the infant for life and gave it status as an individual. These tasks were performed so often as to be commonplace, yet they were heavy with meaning at each new birth, for such rituals were elemental to the existence of women in early America.

Being a mother and rearing a healthy family were the ultimate achievements for a woman in the North American Indian societies. There was no confusion about the role of a woman and very few other acceptable patterns for feminine existence. Many Indian women attained distinction as craftswomen or medical practitioners, but this in no way affected their role as bearers and raisers of children.

Women's lives flowed into what they saw as the natural order of the universe. Mother Earth was fecund and constantly replenishing herself in the ongoing cycle of birth, growth, maturity, death, and rebirth. The primitive women of our continent considered themselves an integral part of these ever-recurrent patterns and accepted a role in which they were an extension of the spirit mother and the key to the continuation of their race. Not separate from, but part of, these deeply religious feelings was the practical consideration that many children were needed to help with the work and to take care of the parents as they grew older. In those simpler days, children were a couple's savings account and insurance.

SEX AND PREGNANCY

Women in most Native American cultures knew pretty clearly how they got pregnant, although even here beliefs varied when it came to the details.

The Gros Ventres of Montana and the Chiricahua Apaches of southern Arizona were among those groups believing that pregnancy could not occur as the result of a single sex act. One Apache explained that if a couple had intercourse three times a week they could have a baby started in about two or three months. But the informant also said, "I know a girl who had intercourse with a man many times in one night. If a girl did it at that rate, it wouldn't take any time at all to get a child started." As another Apache related, "When a man has intercourse with a woman some of his blood (semen) enters her. But just a little goes in the first time and not as much as the woman has in there. The child does not begin to develop yet because the woman's blood struggles against it. The woman's blood is against having the child; the man's blood is for it. When enough collects, the man's blood forces the baby to come."

Although many sexual encounters were believed necessary to create a child, as soon as an Apache woman noticed the first signs of pregnancy, she ceased her sexual activity to prevent injury to the baby growing within her.

The Hopi of northern Arizona, on the other hand, were convinced that continued sex was good for both the prospective mother and the baby; a woman slept with her husband all through her pregnancy so that their continued intercourse could make the child grow. It was likened by one Hopi to irrigating a crop -- if a man started to make a baby and then stopped, his wife would have a hard time.

The Kaska Indians of northwestern Canada also maintained that repeated sex during early pregnancy developed the embryo, but warned that too much indulgence would produce twins. As soon as a Kaska woman felt the stirrings of life in her womb, she was warned to discontinue her sexual life. Mothers advised their pregnant daughters to use their own blankets and to sleep facing away from their husbands to avoid temptation.

Among most of the tribes, however, pregnant women continued a moderate sex life until the later stages of their pregnancy, much as many women do today. There were a few groups where custom completely forbade intercourse during pregnancy. In the area which is now Wisconsin, Fox women abstained from sex throughout pregnancy for fear their babies would be born "filthy," and down near where the Colorado River emptied into the Gulf of California, pregnant Cocopah women slept alone lest their babies be born feet first.

A BOY -- OR A GIRL?

Most Indian mothers welcomed each baby regardless of sex and wished primarily that the child be strong and healthy. But it is universal for a woman carrying a child for nine long months to wonder whether her labor will produce a son or a daughter. Out on the Great Plains when an Omaha woman wanted to ascertain the sex of her coming child she took a bow and a burden strap to the tent of a friend who had a child who was still too young to talk. She offered the two articles to the baby. If the little child chose the bow, the unborn would be a boy; if the child paid more attention to the burden strap, the coming baby would be a daughter.

There were some societies, particularly those in the far north where life was hard, that did not welcome an abundance of daughters. But it is said that the Huron, who lived north of Lake Ontario, rejoiced more at the birth of a girl child, for girls grew into women who had more babies, and the Huron wanted many descendants to care for them in their old age and protect them from their enemies.

In the matrilineal societies of the Hopi in the Southwest, where the status of women was high, a woman wished to give birth to many girl babies, for it was through her daughters that a Hopi woman's home and clan were perpetuated. A boy was not unwelcome, for he also belonged to his mother's clan, but when he married, his children would belong to the house and clan of their own mother.

Generally the sex of the baby was left to fate, but among the Zuni, neighbors of the Hopi on the beautiful but arid and windswept deserts of the Southwest, if a couple desired a girl child they went to visit the Mother Rock near their pueblo. The base of the rock was covered with symbols of the vulva and was perforated with small excavations. The pregnant woman scraped a tiny bit of the rock into a vase and placed it in one of the cavities. Then she prayed that a daughter would be born who would be good, beautiful, and virtuous, and who would display skill in the arts of weaving and pottery-making. If by chance a boy child was born, the Mother Rock was not blamed. Instead it was believed that the heart of one of the parents was "not good."

PRENATAL HEALTH CARE

In those early days, infant mortality was alarmingly high and many women died in childbirth. Prospective mothers used every means at their disposal to ensure safe delivery and healthy children, but because medicinal procedures were so primitive, these women relied on measures which today we label "superstition" and "sympathetic magic," including a vast and varied range of taboos. Pregnant Indian women were almost universally warned against looking at or mocking a deformed, injured, or blind person for fear their babies would evidence the same defect; being in the presence of dying persons and animals was likewise unhealthy for both the mother and baby. Among the Flathead Indians of Montana neither the mother nor father could go out of the lodge backward or a breech birth would follow, nor were either of the prospective parents allowed to gaze out of a window or door. If they wanted to see what was going on outside, they were to go all the way outdoors and look around, lest the baby be stillborn.

There were also taboos on certain foods. Some typical dietary restrictions for pregnant Indian women prohibited eating the feet of an animal, to avoid having the baby born feet first; the tail of an animal, to prevent the child's getting stuck on the way out; berries, so that the baby would not carry a birthmark; and liver, which would darken the child's skin.

The Lummi Indians of what is now northwest Washington were a fairly wealthy group whose home on the productive coastlands offered them a vast variety of foods. This bounty enabled them to place taboos on many foods, including halibut, which was believed to cause white blotches on the baby's skin; steelhead salmon, which caused weak ankles; trout, which produced harelip; and seagull or crane, which would produce a crybaby. The prospective mother also had to abstain from shad or blue cod, which would induce convulsions in the child; venison, which would lead to absentmindedness; and beaver, which might cause an abnormally large head.

Among some of the groups with less abundant food resources, restrictions were limited to only certain parts of animals. Pregnant women were warned that eating tongue would cause the baby's tongue to loll, while the ingestion of an animal's tail might create problems during labor.

Though there were many foods that could not be eaten, there is some evidence that Indian women years ago, like many present-day women, did have cravings for special foods during pregnancy. The Reverend John Heckewelder, writing in the late 1700s, reported that he had witnessed what he called "a remarkable instance of the disposition of Indians to indulge their wives." Apparently, famine had struck the Iroquois in the winter of 1762, but a pregnant woman of that tribe longed for some Indian corn. Her husband, having learned that a trader at Lower Sandusky had a little of the desired commodity, set off on horseback for the one-hundred-mile trek. He brought back as much corn as filled the crown of his hat, but he returned walking and carrying his saddle, for he had had to trade his horse for the corn. Heckewelder continued, "Squirrels, ducks and other like delicacies, when most difficult to be obtained, are what women in the first stages of their pregnancy generally long for. The husband in every case will go out and spare no pains nor trouble until he has procured what is wanted. The more a man does for his wife, the more he is esteemed, particularly by the women."

Each tribe had certain herbs and teas that were believed to relieve aches and pains and promote the health of prospective mothers. A Crow medicine woman named Muskrat used two roots which had been revealed to her by a supernatural who appeared to her twice while she was asleep. During the first vision she was instructed to chew a certain weed if she wished to give birth without suffering. Later she was taught about another plant and was told it was even better than the first. Another Crow woman paid a horse to a visionary who taught her a formula made from a combination of certain roots and powdered, dry horned toad. The resulting powder was used in giving backrubs.

Bear's Medicine for Pregnant Women

(HUPA)

While walking in the middle of the world Bear got this way. Young grew in her body. Ail day and all night she fed. After a while she got so big she could not walk. Then she began to consider why she was in that condition. "I wonder if they will be the way I am in the Indian world?" She heard a voice talking behind her. It said, "Put me in your mouth. You are in this condition for the sake of the Indians." When she looked around she saw a single plant of redwood sorrel standing there. She put it into her mouth. The next day she found she was able to walk. She thought, "It will be this way in the Indian world with this medicine. This will be my medicine. At best not many will know about me. I will leave it in the Indian world. They will talk to me with it."

But besides consuming herbal medicines, avoiding certain foods, and watching their own behavior, some Indian women had to be careful not to become victims of witchcraft during pregnancy. Matilda Cox Stevenson, who lived with and studied the Zuni Indians in the area of northwest New Mexico for many years in the late 1800s, wrote that she had helped a pregnant Zuni woman who was suffering from a cough and from pain in the abdomen. Although the woman felt better after taking the simple home remedies Mrs. Stevenson gave her, her family still thought it wise to call in the native surgeon. When he arrived and began to treat the pregnant woman, he appeared to draw from her abdomen two objects which he claimed were mother and child worms. Mrs. Stevenson wrote that one was about the length of her longest finger, while the other was smaller. The doctor pronounced this evidence that the woman had been bewitched and assured the family that it was well he had been sent for promptly, for in time these worms would have eaten the child and caused its death. Later, when trying to figure out who could have bewitched her, the Zuni woman recalled that some weeks before she had been grinding corn while kneeling next to the sister of a witch, and this woman had touched her on the abdomen. She decided it was probably then that the worms had been cast in.

CHILDBIRTH CUSTOMS

Because in some groups the older women were unwilling to talk about the actual birth process, many young Indian women were remarkably unprepared for the birth of their first child. Pretty-shield, a Crow woman whose story is told in the book Red Mother, related how she was playing with some girl friends during her first pregnancy and felt a quick little pain. When she sat down laughing about it, one of her friends guessed what the pain meant and warned Pretty-shield's mother, who immediately consulted a medicine woman named Left-hand. The mother and Left-hand had to coax Prettyshield to come with them to the special skin lodge they had pitched for the occasion. Outside the lodge Pretty-shield noticed that one of her father's best horses was tied up with several costly robes on his back -- an advance payment to old Left-hand for her assistance. Pretty-shield described the medicine woman as having her face painted with mud, her hair tied in a big clump on her forehead and carrying in her hand some of the grass-that-the-buffalo-do-not-eat.

Inside the tipi a fire was burning and a mat made of a soft buffalo robe was folded with the hair side out to serve as a bed. As was customary, two stakes had been driven into the ground, and other buffalo robes had been rolled up and piled against them so that when Pretty-shield knelt on the mat and took hold of the stakes her elbows rested on the pile of robes.

First Left-hand took four live coals from the fire, spacing them evenly on the ground between the door of the tipi and the bed. Then she instructed her patient to step over the coals and go to the bed. Left-hand, wearing a buffalo robe and grunting like a buffalo cow, followed behind Pretty-shield, instructing her to "walk as though you are busy" and brushing the girl's back with the tail of the robe.

Pretty-shield concludes, "I had stepped over the second coal when I saw that I should have to run if I reached my bed-robe in time. I jumped the third coal, and the fourth, knelt down on the robe, took hold of the two stakes, and my first child, Pine-fire, was there with us."

Anthropologist Ruth Underhill tells a somewhat similar tale in The Autobiography of a Papago Woman. Chona, a Papago woman of southern Arizona, described the birth of her first child, which occurred when she herself was but a teenager. She didn't know quite when to expect her baby, but when she felt a pain one day while stooping over to pass through the low door to her grass house, she surmised that the time had come for the baby's arrival. As was true for women among many North American Indian cultures, Papago mothers were required by custom to have their babies in a special segregation hut apart from the main dwelling. Chona knew that it was time to go to the "Little House" and did not wish to have such a dreadful thing happen to her as to be caught inside the regular house in childbirth. She announced her destination to her husband's aunt -- her first mention of labor pains -- and left to cross the wash between the main house and the Little House.

"When I reached the near edge of that gully I thought I had better run," Chona related. "I ran fast; I wanted to do the right thing. But I dropped my first baby in the middle of the gully. My aunt came and snipped the baby's navel string with her long fingernail. Then we went on to the Little House." Later one of her sisters-in-law asked her why she hadn't said anything about her pains. The other women hadn't known she was suffering because they had heard her laughing. Chona's response was, "Well, it wasn't my mouth that hurt. It was my middle."

Chona and her baby had to stay in the segregation hut for a full month, during which time she was not allowed to bathe, for fear she would get rheumatism. Her family brought her food which she cooked with no salt. "When the moon had come back to the same place," it was time for the purification ceremony. Chona, her husband, and the baby went to a medicine man, or shaman, who was a specialist in child-naming. The shaman prepared a mixture of clay, water, and pounded owl feathers which both parents and the child were required to sip; then the shaman gave the child a name. If Papago parents neglected to have this ceremony performed, they risked the health of both themselves and the new baby.

Not all Indian women had births as easy as those of Pretty-shield and Chona, but they were nevertheless expected to endure the pain without crying out. Huron women who fussed while they were in labor were chided for being cowardly and failing to set a good example for others. A Huron woman proved her courage by her brave conduct during childbirth just as a man proved his courage in battle. The Gros Ventres of Montana believed that a woman who cried out drove the child back, and a mother who turned and twisted in pain might tangle the cord around the child.

During her labor an Indian woman was usually assisted by her female relatives or other women of her tribe who had special knowledge of birth customs. They supported the woman as she knelt or squatted, rubbed her back, pressed down on her abdomen to force the child out, encouraged the mother, and cared for her and the child immediately after the birth. A good example of how the women helped each other can be found among the Kwakiutl of British Columbia. In good weather a woman might deliver outside, but in bad weather she remained in the longhouse. Usually two professional midwives came to assist. They first dug a pit and lined it with soft cedar bark. Then one of them sat down on the edge of the shallow excavation, stretching her legs across it so that her feet and calves rested on the opposite edge. The pregnant woman sat on the midwife's lap, straddling the helper's legs so that both her own legs hung down inside the pit. The two women clasped each other's arms tightly, while the second midwife squatted behind the woman who was delivering, pressing her knees against her back, wrapping her arms around the mother's shoulders, and blowing down her neck in order to produce a quick and easy delivery. The baby dropped into the pit and remained there until the afterbirth was delivered. Then the mother went to bed for four days.

Some of the midwives were quite skilled at their profession, often being able to turn a baby in the womb to ensure a safer and easier delivery. They were also good psychologists, knowing just how to talk to, calm, and comfort a woman who was suffering a great deal. But sometimes, in very difficult cases, the power and skill of the midwives were not enough, and doctors with more power had to be called in. A Gros Ventre woman told of how she had been helped by such a doctor during one of her pregnancies. The man was old and blind and when called to help, he sat next to the suffering woman with a pot of medicine beside him. When the woman cried out in pain he touched her with the end of a stick and the cramps went away. When the woman complained that she was tired, the midwife assured her that it would soon be over, but the doctor disagreed. The labor continued for several more hours until the doctor predicted the baby would be born shortly, and he was right. It was believed that the medicine man's power allowed him to know what was happening without seeing or touching the laboring woman.

Although women generally gathered together for the birth of babies, in some North American tribes the expectant mother had to face the birth process alone. Women in the Caddo group near the border of what are now Mississippi and Arkansas were instructed, when the time of their delivery neared, to go to the bank of the nearest river and to build a little shelter, with a strong forked stick positioned in the center. Supporting themselves with this stick they gave birth all alone and then immediately waded into the stream, even if they had to break ice to do so, washed themselves and the baby, and returned home to continue their normal lives.

A report survives from 1790 of four Tukabahchee women (a tribe of the Greek confederacy located in Alabama) who came to sell horse ropes to some white men on a cold and rainy night in December. Because of the bad weather, the women stayed overnight, and about midnight, one of the women went into labor. Her mother instructed her to take fire and go to the edge of a swamp about 160 yards away. She went alone, delivered her own baby, and the next morning took the infant on her back and returned home with the other women through the still-falling rain and snow.

Many of the native North American cultures insisted that, following birth, both mother and newborn child remain in seclusion, particularly away from all men, for a period of time ranging from a few days to as long as three months. The Nez Percé women in northern Idaho entered a special underground lodge two or three months before the baby was expected and remained for two weeks after the birth. For the most part, women in seclusion were well cared for. Life for them was hard, and rather than being chagrined at being excluded from the rest of the group, they no doubt welcomed a time of recuperation before returning to their strenuous daily duties.

CEREMONIES OF CHILDBIRTH

In some of the Indian societies, a great deal of ritual accompanied each birth. The Hopi infant began life in a society where elaborate religious ceremonials dominated much of village life. Each new baby was immediately immersed in the rich, sacred traditions that would so fully shape its life experience. In the Hopi pueblos a young mother was often alone at the moment of birth, but as soon as the baby had slipped out of the birth canal onto the patch of warm sand, the newborn's maternal grandmother entered the room to sever and tie the cord and to make her daughter and new grandchild comfortable. After washing the baby she rubbed its body with ashes from the corner fireplace so that its skin would always be smooth and free of hair. Then she took the afterbirth and deposited it on a special placenta pile at the edge of the village.

Very soon the baby's paternal grandmother arrived and began to take up her duties as mistress of ceremonies for all the rituals that would be performed during the twenty-day lying-in period and for the culminating dedication of the baby to the sun. Her first task was to secure a heavy blanket over the door so that no sunlight could enter the room where the mother and baby lay. It was thought that light was harmful to newborn children, and so the baby began its life on earth in a room almost as dark as the womb from which it had just emerged.

For eighteen days the mother and baby lay at rest in the darkened room. Each day a mark was made on the wall above the baby's bed and a perfect ear of corn laid under each mark. On the nineteenth day the mother got up and spent the day grinding corn into sacred meal to be used in the special ceremony the next day.

On the next morning the new mother's female relatives arrived at her home well before dawn, dressed in their most colorful shawls and carrying gifts of cornmeal and perfect ears of corn. When all the guests had arrived the solemn ceremony for the dedication of a new life was begun. First the mother was ritually purified. Her hair and body were washed in suds made from the root of the yucca plant, and then she took a steambath by standing over a bowl of hot water. Next all the grandmothers and the aunts each took a turn at bathing the baby in yucca suds and giving it a name.

While all this was taking place inside the home, the father, who since the birth had been living in his religious society's kiva, or underground ceremonial chamber, was stationed on the flat roof of the stone house watching for the sun. When the sacred Sun Father began to appear, the father alerted the women, who hastily took the child to the edge of the mesa. The grandmother who carried the baby crouched low so that no light would fall on the infant. Then, as the sun appeared over the horizon, the grandmother lifted the baby, turning her tiny bundle so the rays fell directly on the little face. Taking a handful of prayer meal she sprinkled some over the baby while reciting a short prayer. She flung the rest of the meal over the edge of the mesa toward the sun. The baby, now a full member of the family, was taken home and allowed to nap while the rest of the family enjoyed a breakfast feast.

Zunis recognized the sex of a baby in a special ceremony performed soon after birth: the newborn female child had a gourd placed over her vulva so that her sexual parts would be large, and the penis of a baby boy was sprinkled with water so that his organs would be small. Of course this ceremony was performed by the women attending the new mother so it reflected the feminine ideal for the physical proportion of the sexual organs.

Because of the extremely high infant mortality rate among the early Native Americans, ceremonials were often delayed until the child was about a year old.