Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

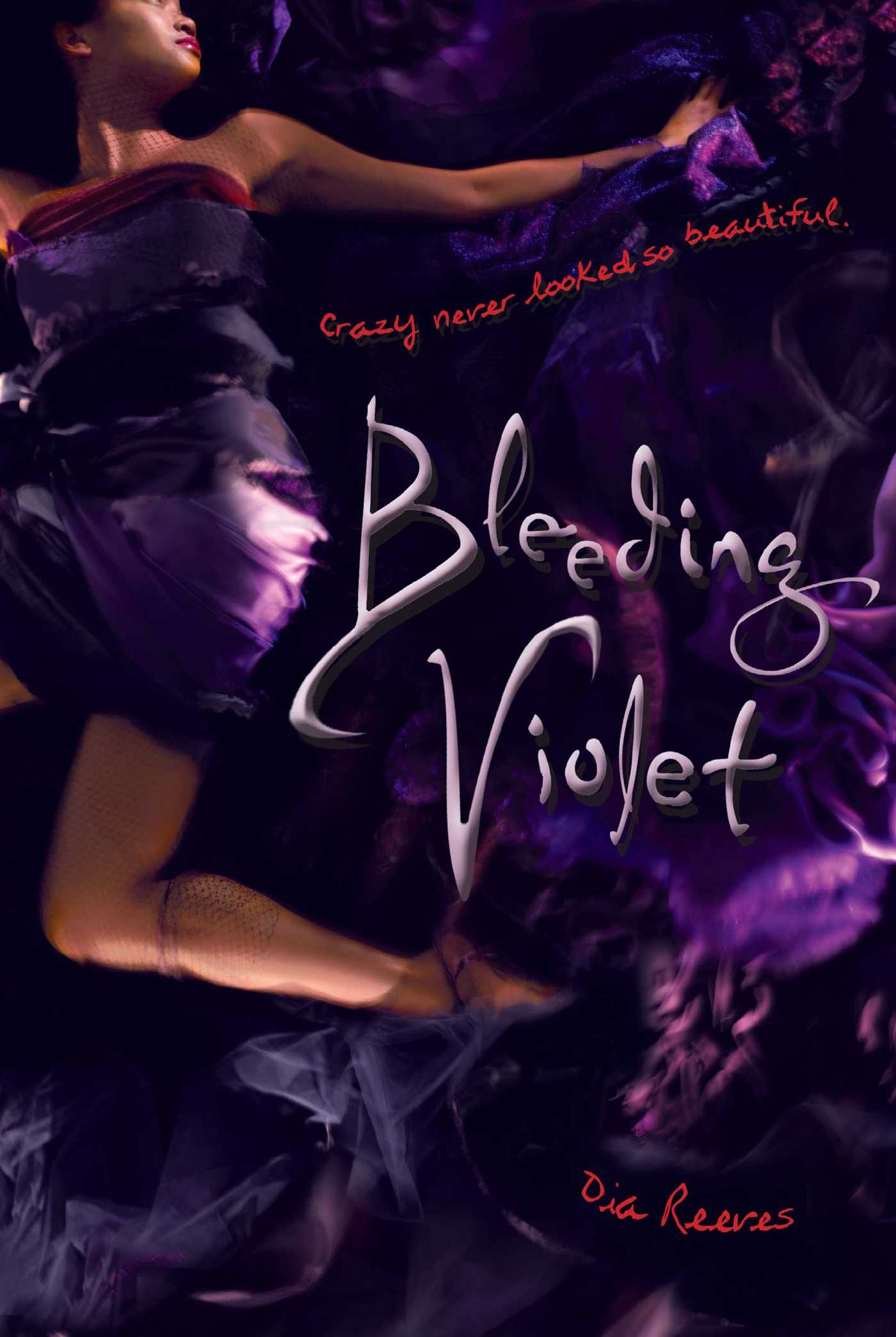

About The Book

Hanna simply wants to be loved. With a head plagued by hallucinations, a medicine cabinet full of pills, and a closet stuffed with frilly, violet dresses, Hanna’s tired of being the outcast, the weird girl, the freak. So she runs away to Portero, Texas, in search of a new home.

But Portero is a stranger town than Hanna expects. As she tries to make a place for herself, she discovers dark secrets that would terrify any normal soul. Good thing for Hanna, she’s far from normal. And when a crazy girl meets an even crazier town, only two things are certain: Anything can happen and no one is safe.

But Portero is a stranger town than Hanna expects. As she tries to make a place for herself, she discovers dark secrets that would terrify any normal soul. Good thing for Hanna, she’s far from normal. And when a crazy girl meets an even crazier town, only two things are certain: Anything can happen and no one is safe.

Excerpt

Bleeding Violet

Chapter One

The truck driver let me off on Lamartine, on the odd side of the street. I felt odd too, standing in the town where my mother lived. For the first seven years of my life, we hadn’t even lived on the same continent, and now she waited only a few houses away.

Unreal.

Why didn’t you have the truck driver let you off right in front of her house? Poppa’s voice echoed peevishly in my head, as if he were the one having to navigate alone in the dark.

“I have to creep up on her,” I whispered, unwilling to disturb the extreme quiet of midnight, “otherwise my heart might explode.”

What’s her house number?

“1821,” I told him, noting mailboxes of castles and pirate ships and the street numbers painted on them. I had to fish my penlight from my pack to see the numbers; streetlights were scarce, and the sky bulged with low, sooty clouds instead of helpful moonlight.

Portero sat in a part of East Texas right on the tip of the Piney Woods; wild tangles of ancient pine and oak twisted throughout the town. But here on Lamartine, the trees had been tamed, corralled behind ornamental fences and yoked with tire swings.

“It’s pretty here, isn’t it?”

Disturbingly pretty. said Poppa. Where are the slaughterhouses? The oil oozing from every pore of the land? Where’s the brimstone?

“Don’t be so dramatic, Poppa. She’s not that bad. She can’t be.”

No? His grim tone unnerved me as it always did when he spoke of my mother. Rosebushes and novelty mailboxes don’t explain her attitude. I never imagined she would live in such a place. She isn’t the type.

“Maybe she’s changed.”

Ha!

“Then I’ll make her change,” I said, passing a mailbox shaped like a chicken—1817.

How had I gotten so close?

A few short feet later, I was better than close—I was there: 1821.

My mother’s house huddled in the middle of a great expanse of lawn. None of the other houses nestled chummily near hers; even her garage was unattached. A lone tree decorated her lawn, a sweet gum, bare and ugly—nothing like her neighbors’ gracefully spreading shade trees. Her mailbox was strictly utilitarian, and the fence that circled her property was chin high and unfriendly.

Ah. said Poppa, vindicated. That’s more like it.

I ignored him and crept through the unfriendly gate and up the porch steps. The screen door wasn’t locked—didn’t even have a lock—so I let myself into the dark space and sat in the little garden chair to the left of the front door. I sat for a long time, catching my breath. I sat and I breathed. I breathed and I sat—

Stop stalling, Hanna.

My hands knotted over my stomach, over the swarm of butterflies warring within. I gazed at the dark length of the front door, consumed with what was on the other side of it. “Do you think she’ll be happy to see me?” I asked Poppa. “Even a little?”

Not if you go in with that attitude. Where’s your spine?

“What if she doesn’t believe I’m her daughter?”

You look exactly like her. How many times have I told you? Now, stop being silly and go introduce yourself.

Poppa always knew how to press my “rational” button. “You’re right. I am being silly.” I straightened my dress, hitched up my pack, marched to the front door, and raised my fist to—

NO. The force of the word rattled my brain. Don’t knock. It’s after midnight. You’ll wake her up, and she awakens badly.

“How badly?” I whispered, hand to my ringing skull.

As badly as you.

Uh-oh.

Nine times out of ten, I awoke on my own, naturally, even without an alarm clock, but if I was awoken before I was ready, things could get ? interesting. And apparently, I’d gotten that trait from my mother.

Cool.

Just let yourself in. said Poppa, his advice rock solid as always. It’s practically your house anyway.

I crouched on the porch, the wood unkind to my bare knees, and folded back the welcome mat. A stubby bronze key glinted in the glow of my penlight.

A spare key.

“Only in a small town,” I whispered, snatching it up.

I unlocked the door and slipped inside.

A red metallic floor lamp with spotlights stuck all over it stood in the center of the room. One of the spotlights beamed coldly—as though my mother had known I was coming and had left the light on for me.

Aside from the red chrysanthemums in a translucent vase above the sham fireplace, and the red throw pillow gracing the single chair near the floor lamp, the entire living room was unrelievedly blue-white.

Modern, the same style Poppa had liked—

Still likes. he said.

—and so I immediately felt at home.

My hopes began to rise again.

I slipped the spare key into the pocket of my dress as I traveled down a short hallway, my French heels clicking musically against the blond wood floor. I put my ear to each of the three doors in the hall, until a slow, deep breathing sighed into my head from behind door number three.

My mother’s breath. Soothing and gentle, as if the air that puffed from her lungs was purer than other people’s.

I stood with my head to the door, trying to match my breath to hers, until my ear began to sting from the pressure.

I regarded the door thoughtfully. Fingered the brass knob.

No, I told you. Poppa was adamant. You need to entice her out of bed.

“I know how to do that,” I whispered, the idea coming to me all at once.

I stole into the kitchen and turned on the light near the swinging door. The kitchen, like the living room, was blue-white, with a single lipstick-red dining chair providing the only color, aside from me in my violet dress.

I dumped my purple bag by the red chair and went exploring, and after I learned where she kept the plates, the French bread, and the artisanal cheese, I decided to make grilled-cheese sandwiches. I took no especial pains to be quiet—I wanted her company. I’d traveled more than one hundred miles in three different crapmobiles and an eighteen-wheeler full of beer just to bask in her presence, but it wasn’t until I plated the food that she shoved through the kitchen door.

My grandma Annikki once told me that anyone who looked on the face of God would instantly fall over dead. Looking at my mother—for the first time ever—I wondered if it was because God was beautiful.

I had the same hourglass figure, the same hazel skin, the same turbulence of tight, skinny curls; but while my curls were a capricious brown, hers were shadow black.

Island-girl hair. Poppa whispered admiringly.

I averted my eyes and presented the sandwiches, like an offering. “Do you want any?”

She drifted toward me in a red sleep shirt and bare feet, seeming to bend the air around her. Her mouth was expressive, naturally rosy, and mean. Just like mine. Our lips turned down at the corners and made us look spoiled.

“You broke into my house to fix a snack,” she said, testing the words, her East Texas drawl stretching each syllable like warm taffy. “I better be dreaming this up, little girl.”

“It’s no dream, Rosalee. I’m here. I’m your daughter.”

Her hands clutched her sleep shirt, over her heart, otherwise she didn’t move. Her oil black eyes raked me in a discomfiting sweep.

“My daughter’s in Finland,” she said, the words heavy with disbelief.

“Not anymore. Not for years. I’m here now.” I reached out to touch her or hug her—any contact would have been staggering—but she stepped away from my questing hands, her mean mouth twisting as she spoke my name.

“Hanna?”

“Yes.”

“God.” She seemed to recognize me then, her gaze softening a little. “You even have his eyes.”

“I know.” I marveled over the similarities between us. “Not much else, though.”

Rosalee looked away from me, tugging at her hair as if she wanted to pull it out. “How could he let you come here? Alone. In the middle of the night. Did he crack?”

“He died. Last year.”

She let her hair fall forward, hiding from me, so if any grief or regret touched her face, I didn’t see it.

After a time, Rosalee stalked past me and stood before the picture window. “If he died last year,” she said, “why come to me now? How’d you even know where to find me?”

I sat in the red chair, clashing violently in my purple dress. “I stole your postcard from Poppa’s desk when I was seven, the month before we moved to the States.” I went into my pack for the postcard. It was soft, yellowed with the years. On one side was a photo of Fountain Square, somewhere here in Portero. On the back was my old address in Helsinki, and in the body of the card, the single word “NO.”

I showed it to her. “What were you saying no to?”

Rosalee glanced at the postcard but wouldn’t touch it. She settled herself against the window, her back to the lowering sky. “I don’t remember what question he asked: to marry him, to visit y’all, to love y’all. Maybe all three. No to all three.”

I put the postcard away. “When Poppa and I moved to Dallas, the first thing I did was go to the public library and look up your name in the Portero phone book.”

I’d gotten such a thrill seeing her name in stark black letters, Rosalee Price, an actual person—not a legend Poppa had made up to comfort me whenever I wondered aloud why other kids had mothers and I didn’t.

“I memorized your address and phone number. For eight years I recited them to myself before I went to sleep, like a lullaby. I didn’t bother to contact you, though. Poppa had warned me what to expect if I tried. That’s why I just showed up on your doorstep—I didn’t want to give you a chance to say no.”

She regarded me with a reptilian stillness, unmoved by my speech. “Who’ve you been staying with since he died?”

“His sister. My aunt Ulla.”

“She know you’re here?”

“Even our feet are the same.”

“What?”

I took off my purple high heels and showed her my skinny feet—the long toes and high arches. Exactly like hers.

“I asked you about your aunt,” said Rosalee, still unmoved.

I admired the sight of our naked feet, settled so closely together, golden against the icy sheen of the kitchen tile.

“I didn’t even know I looked like you. I figured I did. Poppa told me I did. I knew I didn’t look like anybody on Poppa’s side of the family. They’re all tall and blond and white as snow foxes. And here I am, tallish and brunette and brown as sugar. Just like you. My grandma Annikki used to say if I hadn’t been born with gray eyes, no one would have known for sure that I belonged to them. And I did belong to them, but I belong to you, too. I want to know about you.”

That Sally Sunshine act won’t work on her. Poppa warned.

But it was working. As I spoke, Rosalee’s gaze remained focused on me, her unswerving interest startling but welcome in light of her antagonism.

“Poppa told me some things. He’d tell me how beautiful you were, but in the same breath, he’d curse you and say you were dead on the inside. So I’ve always thought of you that way—an undead Cinderella, greenish and corpselike, but wearing a ball gown. Do you even have a ball gown? I could make one for you. I make all my own clothes. I made this dress. Isn’t it sweet?” I stood so she could admire it. “I always feel like Alice when I wear it. That would make this Wonderland, wouldn’t it? And you the White Rabbit—always out of reach.”

“Why do you have blood on your dress?”

Her intense scrutiny made sense now. She hadn’t been interested in me, but in my bloodstains. I followed her gaze to the two dark smidges near my waist.

Sally Sunshine and her bloodstained dress. said Poppa, disappointed in me. I told you to change clothes, didn’t I?

I fell back into the red chair, the skirt of my dress flouncing about my knees, refusing to let Poppa’s negativity derail me.

“What makes you think that’s blood? That could be anything. That could be ketchup.”

“That ain’t ketchup,” Rosalee said. “And this ain’t Wonderland. This is Portero—I know blood when I see it.”

I nibbled my food silently.

“Whose blood is that?”

Tell her. Poppa encouraged. I guarantee she won’t care.

“It’s Aunt Ulla’s blood,” I said. “I hit her on the head with a rolling pin.”

I risked another glance into her face. Nothing.

Told you.

“And?” Rosalee prompted.

Did she want details?

“Aunt Ulla’s blood spurted everywhere, onto my dress, into my eyes.” I blinked hard in remembrance. “It burned.” I fingered the smidges at my waist. “I thought I’d cleaned myself up, but apparently—”

“Hanna.” Despite her apathy, Rosalee addressed me with an undue amount of care, as though I were a rabid dog she didn’t want to spook. “Did you kill your aunt?”

I ate the last bit of grilled cheese. I licked the grease from my fingers. “Probably.”

Chapter One

The truck driver let me off on Lamartine, on the odd side of the street. I felt odd too, standing in the town where my mother lived. For the first seven years of my life, we hadn’t even lived on the same continent, and now she waited only a few houses away.

Unreal.

Why didn’t you have the truck driver let you off right in front of her house? Poppa’s voice echoed peevishly in my head, as if he were the one having to navigate alone in the dark.

“I have to creep up on her,” I whispered, unwilling to disturb the extreme quiet of midnight, “otherwise my heart might explode.”

What’s her house number?

“1821,” I told him, noting mailboxes of castles and pirate ships and the street numbers painted on them. I had to fish my penlight from my pack to see the numbers; streetlights were scarce, and the sky bulged with low, sooty clouds instead of helpful moonlight.

Portero sat in a part of East Texas right on the tip of the Piney Woods; wild tangles of ancient pine and oak twisted throughout the town. But here on Lamartine, the trees had been tamed, corralled behind ornamental fences and yoked with tire swings.

“It’s pretty here, isn’t it?”

Disturbingly pretty. said Poppa. Where are the slaughterhouses? The oil oozing from every pore of the land? Where’s the brimstone?

“Don’t be so dramatic, Poppa. She’s not that bad. She can’t be.”

No? His grim tone unnerved me as it always did when he spoke of my mother. Rosebushes and novelty mailboxes don’t explain her attitude. I never imagined she would live in such a place. She isn’t the type.

“Maybe she’s changed.”

Ha!

“Then I’ll make her change,” I said, passing a mailbox shaped like a chicken—1817.

How had I gotten so close?

A few short feet later, I was better than close—I was there: 1821.

My mother’s house huddled in the middle of a great expanse of lawn. None of the other houses nestled chummily near hers; even her garage was unattached. A lone tree decorated her lawn, a sweet gum, bare and ugly—nothing like her neighbors’ gracefully spreading shade trees. Her mailbox was strictly utilitarian, and the fence that circled her property was chin high and unfriendly.

Ah. said Poppa, vindicated. That’s more like it.

I ignored him and crept through the unfriendly gate and up the porch steps. The screen door wasn’t locked—didn’t even have a lock—so I let myself into the dark space and sat in the little garden chair to the left of the front door. I sat for a long time, catching my breath. I sat and I breathed. I breathed and I sat—

Stop stalling, Hanna.

My hands knotted over my stomach, over the swarm of butterflies warring within. I gazed at the dark length of the front door, consumed with what was on the other side of it. “Do you think she’ll be happy to see me?” I asked Poppa. “Even a little?”

Not if you go in with that attitude. Where’s your spine?

“What if she doesn’t believe I’m her daughter?”

You look exactly like her. How many times have I told you? Now, stop being silly and go introduce yourself.

Poppa always knew how to press my “rational” button. “You’re right. I am being silly.” I straightened my dress, hitched up my pack, marched to the front door, and raised my fist to—

NO. The force of the word rattled my brain. Don’t knock. It’s after midnight. You’ll wake her up, and she awakens badly.

“How badly?” I whispered, hand to my ringing skull.

As badly as you.

Uh-oh.

Nine times out of ten, I awoke on my own, naturally, even without an alarm clock, but if I was awoken before I was ready, things could get ? interesting. And apparently, I’d gotten that trait from my mother.

Cool.

Just let yourself in. said Poppa, his advice rock solid as always. It’s practically your house anyway.

I crouched on the porch, the wood unkind to my bare knees, and folded back the welcome mat. A stubby bronze key glinted in the glow of my penlight.

A spare key.

“Only in a small town,” I whispered, snatching it up.

I unlocked the door and slipped inside.

A red metallic floor lamp with spotlights stuck all over it stood in the center of the room. One of the spotlights beamed coldly—as though my mother had known I was coming and had left the light on for me.

Aside from the red chrysanthemums in a translucent vase above the sham fireplace, and the red throw pillow gracing the single chair near the floor lamp, the entire living room was unrelievedly blue-white.

Modern, the same style Poppa had liked—

Still likes. he said.

—and so I immediately felt at home.

My hopes began to rise again.

I slipped the spare key into the pocket of my dress as I traveled down a short hallway, my French heels clicking musically against the blond wood floor. I put my ear to each of the three doors in the hall, until a slow, deep breathing sighed into my head from behind door number three.

My mother’s breath. Soothing and gentle, as if the air that puffed from her lungs was purer than other people’s.

I stood with my head to the door, trying to match my breath to hers, until my ear began to sting from the pressure.

I regarded the door thoughtfully. Fingered the brass knob.

No, I told you. Poppa was adamant. You need to entice her out of bed.

“I know how to do that,” I whispered, the idea coming to me all at once.

I stole into the kitchen and turned on the light near the swinging door. The kitchen, like the living room, was blue-white, with a single lipstick-red dining chair providing the only color, aside from me in my violet dress.

I dumped my purple bag by the red chair and went exploring, and after I learned where she kept the plates, the French bread, and the artisanal cheese, I decided to make grilled-cheese sandwiches. I took no especial pains to be quiet—I wanted her company. I’d traveled more than one hundred miles in three different crapmobiles and an eighteen-wheeler full of beer just to bask in her presence, but it wasn’t until I plated the food that she shoved through the kitchen door.

My grandma Annikki once told me that anyone who looked on the face of God would instantly fall over dead. Looking at my mother—for the first time ever—I wondered if it was because God was beautiful.

I had the same hourglass figure, the same hazel skin, the same turbulence of tight, skinny curls; but while my curls were a capricious brown, hers were shadow black.

Island-girl hair. Poppa whispered admiringly.

I averted my eyes and presented the sandwiches, like an offering. “Do you want any?”

She drifted toward me in a red sleep shirt and bare feet, seeming to bend the air around her. Her mouth was expressive, naturally rosy, and mean. Just like mine. Our lips turned down at the corners and made us look spoiled.

“You broke into my house to fix a snack,” she said, testing the words, her East Texas drawl stretching each syllable like warm taffy. “I better be dreaming this up, little girl.”

“It’s no dream, Rosalee. I’m here. I’m your daughter.”

Her hands clutched her sleep shirt, over her heart, otherwise she didn’t move. Her oil black eyes raked me in a discomfiting sweep.

“My daughter’s in Finland,” she said, the words heavy with disbelief.

“Not anymore. Not for years. I’m here now.” I reached out to touch her or hug her—any contact would have been staggering—but she stepped away from my questing hands, her mean mouth twisting as she spoke my name.

“Hanna?”

“Yes.”

“God.” She seemed to recognize me then, her gaze softening a little. “You even have his eyes.”

“I know.” I marveled over the similarities between us. “Not much else, though.”

Rosalee looked away from me, tugging at her hair as if she wanted to pull it out. “How could he let you come here? Alone. In the middle of the night. Did he crack?”

“He died. Last year.”

She let her hair fall forward, hiding from me, so if any grief or regret touched her face, I didn’t see it.

After a time, Rosalee stalked past me and stood before the picture window. “If he died last year,” she said, “why come to me now? How’d you even know where to find me?”

I sat in the red chair, clashing violently in my purple dress. “I stole your postcard from Poppa’s desk when I was seven, the month before we moved to the States.” I went into my pack for the postcard. It was soft, yellowed with the years. On one side was a photo of Fountain Square, somewhere here in Portero. On the back was my old address in Helsinki, and in the body of the card, the single word “NO.”

I showed it to her. “What were you saying no to?”

Rosalee glanced at the postcard but wouldn’t touch it. She settled herself against the window, her back to the lowering sky. “I don’t remember what question he asked: to marry him, to visit y’all, to love y’all. Maybe all three. No to all three.”

I put the postcard away. “When Poppa and I moved to Dallas, the first thing I did was go to the public library and look up your name in the Portero phone book.”

I’d gotten such a thrill seeing her name in stark black letters, Rosalee Price, an actual person—not a legend Poppa had made up to comfort me whenever I wondered aloud why other kids had mothers and I didn’t.

“I memorized your address and phone number. For eight years I recited them to myself before I went to sleep, like a lullaby. I didn’t bother to contact you, though. Poppa had warned me what to expect if I tried. That’s why I just showed up on your doorstep—I didn’t want to give you a chance to say no.”

She regarded me with a reptilian stillness, unmoved by my speech. “Who’ve you been staying with since he died?”

“His sister. My aunt Ulla.”

“She know you’re here?”

“Even our feet are the same.”

“What?”

I took off my purple high heels and showed her my skinny feet—the long toes and high arches. Exactly like hers.

“I asked you about your aunt,” said Rosalee, still unmoved.

I admired the sight of our naked feet, settled so closely together, golden against the icy sheen of the kitchen tile.

“I didn’t even know I looked like you. I figured I did. Poppa told me I did. I knew I didn’t look like anybody on Poppa’s side of the family. They’re all tall and blond and white as snow foxes. And here I am, tallish and brunette and brown as sugar. Just like you. My grandma Annikki used to say if I hadn’t been born with gray eyes, no one would have known for sure that I belonged to them. And I did belong to them, but I belong to you, too. I want to know about you.”

That Sally Sunshine act won’t work on her. Poppa warned.

But it was working. As I spoke, Rosalee’s gaze remained focused on me, her unswerving interest startling but welcome in light of her antagonism.

“Poppa told me some things. He’d tell me how beautiful you were, but in the same breath, he’d curse you and say you were dead on the inside. So I’ve always thought of you that way—an undead Cinderella, greenish and corpselike, but wearing a ball gown. Do you even have a ball gown? I could make one for you. I make all my own clothes. I made this dress. Isn’t it sweet?” I stood so she could admire it. “I always feel like Alice when I wear it. That would make this Wonderland, wouldn’t it? And you the White Rabbit—always out of reach.”

“Why do you have blood on your dress?”

Her intense scrutiny made sense now. She hadn’t been interested in me, but in my bloodstains. I followed her gaze to the two dark smidges near my waist.

Sally Sunshine and her bloodstained dress. said Poppa, disappointed in me. I told you to change clothes, didn’t I?

I fell back into the red chair, the skirt of my dress flouncing about my knees, refusing to let Poppa’s negativity derail me.

“What makes you think that’s blood? That could be anything. That could be ketchup.”

“That ain’t ketchup,” Rosalee said. “And this ain’t Wonderland. This is Portero—I know blood when I see it.”

I nibbled my food silently.

“Whose blood is that?”

Tell her. Poppa encouraged. I guarantee she won’t care.

“It’s Aunt Ulla’s blood,” I said. “I hit her on the head with a rolling pin.”

I risked another glance into her face. Nothing.

Told you.

“And?” Rosalee prompted.

Did she want details?

“Aunt Ulla’s blood spurted everywhere, onto my dress, into my eyes.” I blinked hard in remembrance. “It burned.” I fingered the smidges at my waist. “I thought I’d cleaned myself up, but apparently—”

“Hanna.” Despite her apathy, Rosalee addressed me with an undue amount of care, as though I were a rabid dog she didn’t want to spook. “Did you kill your aunt?”

I ate the last bit of grilled cheese. I licked the grease from my fingers. “Probably.”

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers (January 18, 2011)

- Length: 480 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416986195

- Ages: 14 - 99

Browse Related Books

Awards and Honors

- ALA Best Books for Young Adults Nominee

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Bleeding Violet Trade Paperback 9781416986195