Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

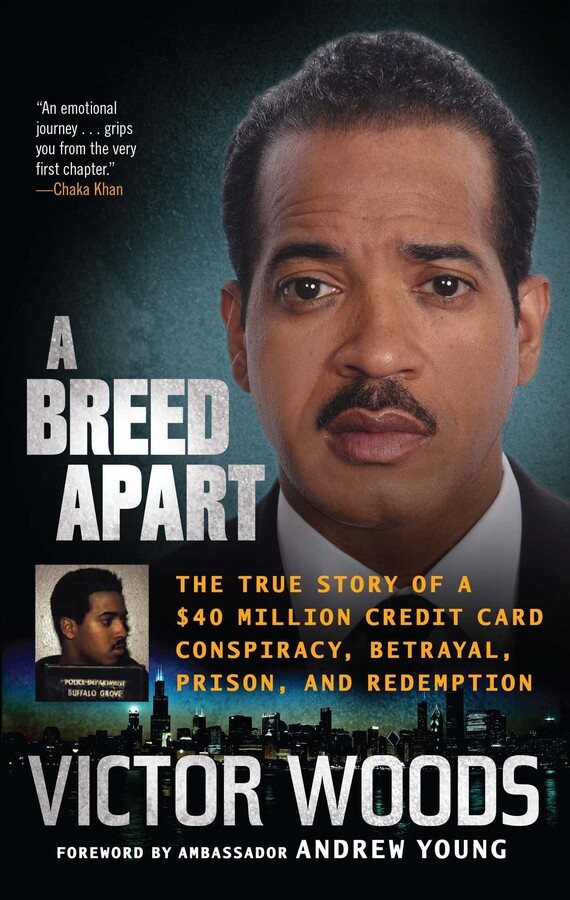

About The Book

In 1990, Victor Woods was charged by the US federal government with organizing a credit card scam worth more than forty million dollars. He refused to implicate his family and friends for a reduced sentence. His lawyer at the time remarked that he was “a breed apart.”

In his authentic, matter-of-fact style, Woods shares the details of his evolution from a rebellious teen to a white-collar criminal and what inspired him to turn his life around while locked away as a federal inmate. Woods’s misdeeds and missteps remind us that sometimes we can be our own worst enemy. His remarkable turnaround shows us that no matter our past we can always make good on a second chance.

Excerpt

It was a lovely Chicago summer day in July 1990. The sun was shining, not a cloud in the sky. My girlfriend and I were cruising down Lake Shore Drive in my Corvette. The convertible top was down, and I could smell the last vestiges of well-seasoned food we'd just eaten from the Taste of Chicago as we passed Grant Park.

The beauty of the sunlight reflecting on Lake Michigan was complimented by a cool breeze from the lake. In a matter of seconds, Soldier Field, home of the Chicago Bears, was behind us. A few minutes later, we passed the Museum of Science and Industry and then onto Stoney Island Avenue. We were on our way to Razor's jewelry store. It was near 69th and Stoney.

When we arrived, Delilah stayed in the car and I went in. I was greeted by Razor's wife, who took my watch and began cleaning it, as she usually did when I visited the store. There was no one else in the store, so we got right down to business.

Razor was a brother in his mid-thirties. I asked him if he had the money as we agreed. His negative reply irritated me. He then asked if I had the merchandise. I told him "No." Obviously, we were both being cautious about the exchange.

I told him the merchandise was nearby, and with a telephone call, it could be dropped off. He said once it was received, we would pick up the money at another location. I was perturbed that we had to alter our original plan. We finally agreed that I would instruct my guy to make the drop, and we would then proceed together to pick up my cash.

I called my guy, Jimmy, and told him to deliver the package to the Holiday Inn in Harvey, Illinois, as Razor requested. Twenty-five minutes later, Razor received a call that the 700 blank Visa Gold credit cards were received, and all was well. I then talked to my guy, and he confirmed that everything was cool.

Razor casually got into his new Thunderbird, and Delilah and I followed him to the drop. Rainbow Beach was also on Chicago's South Side, and not too far from Razor's store. It was afternoon when we arrived at the beach. There were a few cars scattered in the parking lot and several people enjoying the summer day. Razor parked near a Datsun 280Z, and I parked about twenty-five feet away from Razor. Again, I told Delilah to wait in the car.

Everybody got out of their cars simultaneously, looking to the left and to the right, while proceeding toward one another. After we converged, the brother from the 280Z said, "What's up?" He opened a duffel bag he had been carrying on his left shoulder, and showed me the money: $30,000 in 100-dollar bills. He then tried to hand me the duffel bag. I told him no thank you. There was no offense intended, but I didn't know him from Adam. I told him to give the bag to Razor, and Razor would give it to me.

As Razor took the money and reached out to give it to me, the whole parking lot lit up like a Christmas tree. There were undercover agents everywhere. Some were closing in on us in cars, while others were running toward us on foot, guns drawn. It was the most police I had seen in a long time. The United States prosecutor was even in attendance for the show.

All of us were handcuffed and thrown against one of the unmarked police cars. As an agent pressed a shotgun against my head, Razor looked at me and asked if I had set him up. I just looked at him and the other brother in total disgust. On the contrary, I knew I had just been set up. They had Delilah surrounded in my Corvette. She looked over at me and smiled, as if to say it was all some big joke.

I rode downtown in an unmarked car with three Secret Service agents, just as I had three weeks earlier. But then, I knew the game was over. I knew I was headed back to prison. As I was sitting inside the federal building handcuffed to the wall, Lee Seville, the same gray-haired agent who had told me three weeks before to help myself and cooperate with the government, came into the room.

He informed me that my guy Jimmy was telling him so much that I had better start talking before there was nothing left to tell. He said if I didn't talk, I was going to the Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC) in downtown Chicago. At that moment, I knew what I had to do. I began to reflect on the circumstances that had led me to this place and time -- on how I came to find myself in big trouble for the second time.

Well-Bred

My parents never spent much time talking about their parents. However, my father did tell me my great-grandmother was blind and deaf, and she had been raped by an Irishman. As a result, my father's mother was so fair that people thought she was white. I never met my grandfather. They had four children -- my father and his three sisters -- all with light skin. My father's hair was black, but his sisters all had red hair and freckles.

My father, Irving Woods, grew up in Florida at a time when segregation prevailed, and black people regardless of their complexion were treated like dogs. My grandfather left my grandmother, who was a nurse, when their children were small. My father grew up in a tiny house that rested on a dirt road. There was no toilet, only an outhouse. He grew up like most black people in the South at that time: poor and discriminated against. However, he had a tremendous amount of motivation and inner strength. Attending segregated schools that had only secondhand books, he read all he could. He worked odd jobs, and helped his mother, and prided himself on the fact that he never caused his mother any problems. At high school, where he was chosen to lead the band, he already had a good reputation.

Extremely handsome and intelligent, my father was and always had been a very proud man. He told me about a white instructor who administered the driver's test at a motor vehicles bureau, who insisted my father call him "sir."

"I'm not here to Uncle Tom you," replied my father. It was no surprise that my father failed the driving test.

Dad attended Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, where he met my mother, a striking Spelman woman with beautiful honey-brown skin, big brown eyes, and an arresting smile. She was smart, incredibly talented, and had a good sense of humor.

My mother, Deborah Woods, grew up differently from my father and from most black people in the fifties. Raised in a sprawling home surrounded by beautiful things and wanting for nothing, she was the daughter of a prominent Detroit minister who had risen from humble beginnings to the very top of his field. Mama was the most popular girl in her high school and was always the center of attention. She sang and played piano at social gatherings. My mother lived a more privileged existence than most white people. My mother and grandmother told me many stories about my grandfather and how much he loved them and the Lord. Most of the important details about my grandfather were handed down to me by my grandmother.

My maternal grandfather, Rev. Dr. Anderson Major Martin, grew up in Mississippi, left home at an early age for Chicago and received his degree from the Moody Bible Institute. He was flamboyant and always had a new Cadillac. One man who knew my grandfather for years told me he was the most sharply dressed man he had ever seen. He had a pair of shoes and a hat to match each tailored suit. But most importantly, I've been told he was a great family man.

My grandmother, Mary Louise Martin, was a beautiful, extremely intelligent Christian woman from Brooklyn, New York. She adored my grandfather. Her whole world was her two girls, her husband, and the church.

At one time, Rev. Dr. Anderson Major Martin was one of the most respected ministers in the country. His sermons were said to be spellbinding. One Sunday morning, before I was born, he died as he wanted to: preaching in the pulpit to his congregation. Former President Richard Nixon sent flowers to his funeral. Before my grandfather died, he told my grandmother that if anything ever happened to him, he didn't want her to remarry because he wouldn't be able to rest in peace if anybody mistreated her. My grandmother never did remarry. A selfless person who lived to serve God and take care of her family, she worked as a math teacher so my mother and aunt could complete their college educations.

After college, my parents married. It was 1962, and although my father had a college degree, as a black man he had trouble finding a job, so they moved in with my mother's mother. My father took a job at a local grocery store stocking shelves, while continuing to look for a better job. Eventually he secured a job with a Fortune 500 company, and was promoted and transferred frequently.

I was born on March 23, 1964. People said I was a beautiful baby. My mother said that everywhere she took me people would stop her and ask to look at me. My parents were proud and showered me with attention.

My grandmother and I started loving each other from the first time we laid eyes on each other. Her love remains with me to this day. My grandfather's death had left a tremendous void in her life, so when I was born, she dedicated herself to me. As long as she lived she showered me with love, wisdom and knowledge. My grandmother taught math in Detroit for thirty-five years. I remember always going to school with her when I was a little boy. Before I could even walk or talk, I had already formed a strong spiritual bond with Mary Louise Martin.

Grandma treated me like a prince. She constantly showered me with gifts. I was a hyperactive child; I got into anything and everything. I was also spoiled rotten. I began to get into mischief early on. When I was two years old, I locked the baby-sitter out of the house. I ran around so much that she could barely keep up with me. I was so out of control, my doctor prescribed Thorazine to calm me down. Apparently, it rendered me almost comatose. I sat on the couch in front of the TV like a zombie. After a week, my mother felt sorry for me and took me off the medication. She resigned herself to letting me run wild.

At three, my parents enrolled me in Montessori preschool. I was Dennis the Menace, Chuckie from Child's Play, and Damien from The Omen -- all in one. I wouldn't sit when they told me to sit, nor would I stand when they told me to stand. I followed none of the rules and was so disruptive that my mother was often called to pick me up early. Finally, the teachers gave up and told my parents not to bring me back -- by age three, I had been kicked out of school. I had already started to develop a pattern of behavior I would maintain well into my adult life.

I refused to follow rules; it had to be my way or no way. And despite my incorrigible behavior, I could charm people. I had an early grasp of the English language, and people always commented on how well I spoke, how smart I was. Most people thought I was "so cute" and allowed me to get away with just about everything. I recognized that and used it.

When I was three, my mother gave birth to a baby girl. Valerie was a beautiful baby with a head of curly black hair. I used to get my sister into trouble by knocking her food onto the floor while my mother's back was turned. Valerie would cry and my mother would scold her while I sat back, watched, and enjoyed the show. Even though I sometimes got my sister into trouble, we did everything together, and eventually became best friends.

Suburban Life, Jack & Jill and Racism 101

I continued to act the fool in kindergarten. I refused to listen to the teacher or follow the rules. Valerie was the opposite. She was a very quiet child who didn't get into any trouble. My teachers began to tell my parents what they would hear throughout my school experience; I was smart, but didn't listen and wouldn't follow the rules.

My father continued to earn promotions and we were constantly moving. He was successful, and we were comfortable. I never remember wanting for anything during my childhood. My father took excellent care of us, determined to do what his father never tried to do.

Through all the promotions and moves, I maintained an intensely close relationship with my maternal grandmother, Mary Louise Martin. She wrote me loving letters and we talked on the phone. We always spent Christmas at her house in Detroit, or she would visit us. My mother's sister, her husband, and their two children would also gather at my grandmother's house for the holiday festivities.

My grandmother was a fantastic cook. She made cookies and cakes from scratch and the best hot rolls I have ever tasted. I remember sitting at the table watching her make rolls. I would eat the dough, and she'd say, "It's gonna rise in your stomach," and we would burst into laughter.

My grandmother's house seemed like a castle to me. There were two different stairways leading upstairs, five bathrooms, a bar in the basement and an attic as big as most apartments, equipped with a bathroom of its own. My grandfather's study had shelves of books and a handsome desk and chair. A large colored picture of him hung on the wall, and everywhere I moved in that room, my grandfather's eyes would follow.

When we went to see my grandmother, we attended service at Newlight Baptist Church, where my grandfather used to preach. My grandmother was still active in the church and was considered its first lady. The church was so huge that the preacher had to speak through a microphone. There were two choirs and nurses for people who caught the Holy Ghost. When I was growing up, all the people in the church knew and remembered my grandfather, and expressed love and respect for him.

After church service, we were treated like celebrities. People lined up to talk to me and meet the late reverend's grandson. Many old men and women just wanted to kiss me. It used to scare me, but I loved all the attention. I never could begin to imagine that one day I too would find myself in the pulpit, speaking to thousands of people.

My grandmother told me stories about my grandfather so often I felt I knew him personally. Some nights, in bed with my grandmother, I fell asleep in her arms as she talked about him. I was going to preach one day as my grandfather had preached, she said, making sure to keep my grandfather's memory alive. "You're going to talk to large crowds." I disagreed, but she would laugh and say, "You just wait and see."

In the mid-1970s, we moved to Arlington Heights, Illinois, an affluent suburb of Chicago. We were the first black family to move there. A neighbor who befriended my parents told them that others were saying "niggers are moving in" and held a town meeting where they tried to raise enough money for the town to buy the house in order to keep us out. I was in the fourth grade when we moved to Arlington Heights. We had moved from a diverse neighborhood in New York. I knew little about racism. I quickly made friends with a few boys on the block and enjoyed that first summer. But I was going to receive a crash course on racism.

I was unprepared for the first day of school. My sister and I were the first black children to attend Juliette Low Elementary School. I was called "nigger" more times than I care to remember. Although they had never been around anyone black, those white children had been told black people were "niggers." When they saw me, they pointed and called me a "nigger." It was like a child seeing a giraffe in a book for years, then finally going to a zoo and seeing a real one. Racism is taught and learned.

Being the only black in my class was horrible. I hated it. I especially hated it when the teacher would talk about slavery. Each of those white children in class one by one turned to look at me, as the teacher explained the little bit that American public schools share with students about black people and our history.

One day in Social Studies class, we discussed the subject of welfare. One boy in class said his father told him all black people were on welfare. Everybody turned around and looked at me. The teacher admonished him, but the damage was already done. I don't think my parents considered all the cruelties that would be inflicted upon their children when they thrust us in an all-white environment. They had been raised in segregated black environments.

The never-ending battle with my parents remained constant with regard to my behavior at home. I was determined to do things the only way I knew how -- my way. Despite the madness at school, I had a normal childhood. I played baseball, rode my bicycle, and watched TV. Kung Fu was my favorite show; I was a karate man. My grandmother even bought me a karate uniform. I was fascinated with Bruce Lee. I watched his movies and read any book about him I could find.

My second sister was born when I was in the fourth grade. It was an exciting time. After my parents brought my baby sister home, Valerie and I ran home from school and rushed in to see her lying in her crib. I held her, under the watchful eye of my parents.

Vanessa was a beautiful baby and had the Woods's trademark head of hair. She was happy and athletic -- crawling within months and walking early. She would go on to become a track star in junior high and high school.

In addition to sports, my parents involved us in Jack & Jill of America, an exclusive black social organization whose goal was to bring black children from good backgrounds together. At the time its members were mostly upper middle class and wealthy families, but recently they have reached out to less fortunate blacks for membership. Jack & Jill has chapters across the country, and membership is by invitation. Through Jack & Jill, I was able to meet black children from the other suburbs and other cities who were the only blacks in their schools, too, experiencing similar trials and tribulations.

Jack & Jill had local, regional and national politics, with children seeking offices, and mothers trying to get them elected. Annual regional and national conventions allowed us to meet black children from across the country. The only black people I interacted with were those we met when we visited my grandmother in Detroit or through Jack & Jill.

f0

I had a deep hunger in my heart to meet and understand all kinds of black people, not just the black bourgeoisie.

As most years went by, most of the children in my neighborhood grew to accept me, and by junior high school, I was one of the most popular kids in school. Saturday Night Fever, starring John Travolta, was a hit movie and one of my other friends and I put together a routine, tried out for a school talent show, and won. After that, I was invited to all the parties, and the girls always wanted to dance with me.

My grades were always a mess. If I got a C, my parents were happy. I refused to study and couldn't concentrate. I was the class clown and enjoyed making the other children laugh. Being the lone black student I quickly adopted the philosophy: Better to make them laugh with you, than at you.

School was one big party. White kids asked me stupid questions like: What do you do with your hair? Or, do you wear suntan lotion in the summer? I hated the questions, but I knew most of them didn't mean any harm, they were simply ignorant.

The morning after Jimmy Carter had won the presidential election, I was waiting at the bus stop to go to school. My parents had felt good about the election and although I didn't know a thing about politics, I felt good about it, too. I made the mistake of sharing that joy with one of the white boys at the bus stop. "The only reason President Carter won was because all the niggers voted for him," he said. The others started laughing at me. Hurt and disgusted, I retaliated in the way I knew best -- fighting. Hearing the word "nigger" was like pulling the trigger for an ass-kicking from me. In spite of my popularity, I still constantly had to deal with insensitive comments from other students.

On 1950s-day in school, a day everybody dressed up in fifties' attire, one white girl asked me why I bothered to dress up, since there were no black people in the fifties! She never saw any black people on TV show reruns of the era, so we must not have existed.

The irony, however, was all of those white kids were bobbing and hopping to music created and performed by black people. The truly scary thing, though, was that the girl really believed there were no black people in the 1950s. I had to deal with ignorance every day.

I had a few girlfriends in junior high school. All we did was hold hands -- no big deal. In eighth grade being black in an all-white environment became even worse. One night at a party, we started playing spin the bottle. None of the girls wanted to kiss me when the bottle landed on me. When it came to kissing, I was no longer the cute little black kid. I left the party hurt and disturbed. That night marked the beginning of my education on how truly unaccepted I really was in white America.

Freshman Year, High School

Poor grades aside, somehow I graduated from junior high and entered Rolling Meadows High School in 1978. Other than being the class clown and getting poor grades, I was a good kid. I had never stolen anything, nor had I ever tried drugs or alcohol. I was excited about going to high school, but worried at the same time. I knew I would probably be the only black child in the school -- again. There was the threat of upper classmen who were bound to give me a hard time.

Also, there would be an influx of new freshmen from several different junior high schools. That meant having to deal with unfamiliar white kids who probably never went to school with a black kid before. The mere thought sickened me.

I spent the night before my first day of high school worrying about what I was going to wear. I was a simple dresser. I wore what the white kids wore: blue jeans, Colorado boots, and a long-sleeve shirt with the sleeves rolled up.

My first day, I was surprised to see a black girl -- Teresa -- in the freshman class. It was nice to see some more color. I considered my first day of high school good, because nobody called me nigger. (By high school, most white kids knew they shouldn't call blacks niggers, at least not to their face.)

As the year moved on, I settled into being the constantly tardy class clown and throwing things in the classroom. Then I decided to try out for the freshman basketball team. I had spent the summer on the court. My favorite player was Julius Erving, more affectionately known as Dr. J.

Happily, I made the team. My jump shot was only fair, but I had excellent ball-handling skills. I wanted to play like Dr. J., and did exactly that whenever I got the chance. I didn't play much, however, because the coach wanted me to play within the team concept. But I was on the team, and that gave me status.

Then some of my white friends began to make derogatory remarks about black people in my presence. When I took offense and told them so, they would smile and say, "Victor, you're not like one of them, you're one of us."

All I could see was white. I didn't know much about black people, but I knew I wasn't white.

The "spin-the-bottle" incident had assured me I wasn't one of them, and could never be one of them. I didn't want to be one of them. Surrounded by whites, I never wanted to trade my beautiful brown skin and curly black hair for their pale skin and straight hair. I was always proud of who I was.

Midway through the year, Roots by Alex Haley came on TV. Every day at school, students were calling me Kunta Kinte. I hated sitting in history class when we talked about slavery, and black people being less than human. I also disliked civil rights' lessons. When a white person in a classroom movie used the word "nigger," everyone in the class, including the teacher, would look for my reaction. I hated all of that; it made me extremely uncomfortable. Yet, the suburban environment seemed natural, and every other black child I knew in Jack & Jill was going through the same stuff. I just dealt with it the best way I could.

I kept my grades just high enough that I could continue to play basketball. I was obsessed and thought about going pro. I got my first revelation that I wasn't good enough to play pro ball when I went to my grandmother's house for the holiday. I went to the MacKenzie High School gym with one of my cousins who lived in Detroit.

I had only played with kids at my high school. I had never been exposed to a gym full of brothers playing ball. I got on the court and I couldn't keep up. Some brothers, not much bigger than myself, were slamming. I had the unfortunate task of guarding one brother who not only clearly outplayed me, but dunked on me, too. It was a humbling, eye-opening experience.

"Which pro team you want to play for?" I asked that brother after the game.

"I'm not good enough to play pro ball," he replied. At that moment I knew I wasn't going to the NBA.

The rest of my freshman year was uneventful. I continued to be the class clown and my grades were barely above average. I continued to stay clear of any real behavioral problems. I still didn't drink, smoke, take drugs, or steal. That summer, my grandmother came to visit us and I had my first brush with the law.

.

Copyright © 1998 by A Breed Apart Corporation

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (November 1, 2007)

- Length: 304 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416592044

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Victor Woods takes us on an emotional journey . . . . A Breed Apart grips you from the very first chapter. “

– Chaka Khan

“Stingingly conveys the grief and madness . . . . A cautionary tale with a happy ending.”

– Kirkus Reviews

“A life-altering reading experience that contains a priceless and timeless message.”

– Claude Brown, author of Manchild in the Promised Land

“Will inspire and captivate you.”

– Ilyasah Shabazz, daughter of Malcolm X, and author of author of X: A Novel, Malcolm Little, and Growing Up X

“A Breed Apart is a moving, exciting story that’s going to make a great movie.”

– Emmy award-winning actor, Armand Assante

"This book has important social implications . . . . One of the most compelling reads of its genre since Malcolm X."

– David McPherson, former Executive Vice President, Sony Urban Music

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): A Breed Apart eBook 9781416592044

- Author Photo (jpg): Victor Woods Photograph by Susan James Photography(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit